Selfies themselves have exploded in popularity alongside the ever-expanding world of social media. Ellen DeGeneres’ Oscars selfie in 2014 became the most retweeted post in history at 2,070,132 retweets by the end of the Oscars ceremony (Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them, 2014). Tom Hanks congratulated a newly-wed couple by sharing a selfie on Instagram, whilst the UK’s Prime Minister posed for selfies on the red carpet on Monday evening (Theresa Manyia, 2016), all captured in figure one. Figures from 2014 state over 1,000,000 #selfies are taken each day, with 50% of men and 52% of woman having taken a selfie (The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures, 2014). Perhaps it is no surprise then that the selfie phenomena provided an opportunity for the charity Cancer Research UK to raise over £8,000,000 (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). Figure One. Left to right: Ellen’s Oscar selfie, Tom Hanks wedding congratulations selfie, Theresa May posing for red carpet selfies with the public The #nomakeupselfie was initiated by Laura Lipmann, for a different reason and with a different hashtag, but before long the internet had worked its magic and the no make-up selfie was generating tens of thousands of tweets a day. Cancer Research UK noticed the hashtag gaining momentum and attached a donation text number to the posts, raising £2,000,000 in the first 48 hours (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). It is safe to say the no make-up selfies are a perfect example of ‘going viral’. How was it then that a simple selfie influenced so many people to donate? How was a viral phenomenon influencing people’s behaviour a) getting them to upload a post they would not usually post, and b) getting them to donate money they would not have considered doing before-hand? Below are various influence techniques that appear to have been at play throughout the #nomakeupselfie phenomena. Availability Heuristic and Social NormsThe availability heuristic suggests the easier something comes to mind, the higher we estimate the frequency of an event (Schwarz et al, 1991). Agenda setting theory extends this and suggests the media can manipulate what we think about by the frequency of which it shares a story (Walgrave & Aelst, 2006). With tens of thousands of woman engaging, it is not surprising the posts filled our timelines and reached mainstream media (Deller & Tilton, 2015). The no-make up selfie was then at the forefront of our minds, and we very quickly believed that everyone was doing it.Sherif and Sherif (1953) first defined social norms as our standards formed through our group interactions, that we will follow as individuals. Through the surge of no make-up selfie posts, the media ensured we perceived the no-make selfies as the latest norm. In the interest of fitting in and wanting to part of the in-group of our online friendship networks, we soon are likely to have taken the selfie ourselves and are contributing to the mass selfie uploads and adding to the growing donations. Celebrity Endorsement

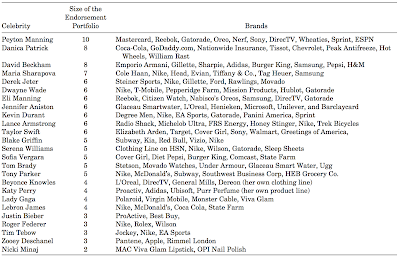

Figure One. Left to right: Ellen’s Oscar selfie, Tom Hanks wedding congratulations selfie, Theresa May posing for red carpet selfies with the public The #nomakeupselfie was initiated by Laura Lipmann, for a different reason and with a different hashtag, but before long the internet had worked its magic and the no make-up selfie was generating tens of thousands of tweets a day. Cancer Research UK noticed the hashtag gaining momentum and attached a donation text number to the posts, raising £2,000,000 in the first 48 hours (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). It is safe to say the no make-up selfies are a perfect example of ‘going viral’. How was it then that a simple selfie influenced so many people to donate? How was a viral phenomenon influencing people’s behaviour a) getting them to upload a post they would not usually post, and b) getting them to donate money they would not have considered doing before-hand? Below are various influence techniques that appear to have been at play throughout the #nomakeupselfie phenomena. Availability Heuristic and Social NormsThe availability heuristic suggests the easier something comes to mind, the higher we estimate the frequency of an event (Schwarz et al, 1991). Agenda setting theory extends this and suggests the media can manipulate what we think about by the frequency of which it shares a story (Walgrave & Aelst, 2006). With tens of thousands of woman engaging, it is not surprising the posts filled our timelines and reached mainstream media (Deller & Tilton, 2015). The no-make up selfie was then at the forefront of our minds, and we very quickly believed that everyone was doing it.Sherif and Sherif (1953) first defined social norms as our standards formed through our group interactions, that we will follow as individuals. Through the surge of no make-up selfie posts, the media ensured we perceived the no-make selfies as the latest norm. In the interest of fitting in and wanting to part of the in-group of our online friendship networks, we soon are likely to have taken the selfie ourselves and are contributing to the mass selfie uploads and adding to the growing donations. Celebrity Endorsement Figure Two: Celebrity endorsement portfolios (Keating & Rice, 2013)Celebrity endorsement ties into the influence of both availability heuristic and social norms, with multiple brands using celebrities to advertise their goods, as outlined in figure two (Keating & Rice, 2013). Research by Keating and Rice (2013) measured recall of products when they were presented with a celebrity (celebrity cue) or with no cue. When looking at their results (displayed in figure three), it is understandable why such a vast majority of brands invest in celebrity marketing techniques, with moderate levels of celebrity cues significantly increasing recall of the products.

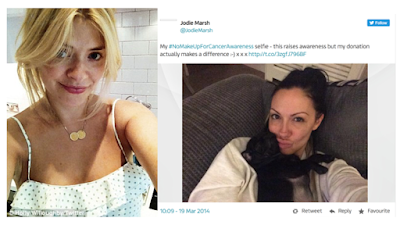

Figure Two: Celebrity endorsement portfolios (Keating & Rice, 2013)Celebrity endorsement ties into the influence of both availability heuristic and social norms, with multiple brands using celebrities to advertise their goods, as outlined in figure two (Keating & Rice, 2013). Research by Keating and Rice (2013) measured recall of products when they were presented with a celebrity (celebrity cue) or with no cue. When looking at their results (displayed in figure three), it is understandable why such a vast majority of brands invest in celebrity marketing techniques, with moderate levels of celebrity cues significantly increasing recall of the products.  Figure Three: Percentage of consumers who recalled the product with and without celebrity cues (Keating & Rice, 2013)If we extend this outside of purchasing environments, individuals are likely to have higher chances of recalling a given ‘thing’ if a celebrity has been associated with it. Once again, the availability heuristic is at play; if the celebrities are taking part (as demonstrated by Holly Willoughby and Jodie Marsh in figure three), everyone must be doing it. Thus, we are more likely to upload a no make-up selfie ourselves and make a donation in order to fit in with the ever-growing social norms.

Figure Three: Percentage of consumers who recalled the product with and without celebrity cues (Keating & Rice, 2013)If we extend this outside of purchasing environments, individuals are likely to have higher chances of recalling a given ‘thing’ if a celebrity has been associated with it. Once again, the availability heuristic is at play; if the celebrities are taking part (as demonstrated by Holly Willoughby and Jodie Marsh in figure three), everyone must be doing it. Thus, we are more likely to upload a no make-up selfie ourselves and make a donation in order to fit in with the ever-growing social norms. Figure Three. Left to right: Holly Willoughby’s and Jodie Marsh’s #nomakeupselfieRole ModelsIn addition, celebrities are traditionally seen as attractive and likeable individuals who are considered to be highly influential (Kamins et al, 1989), and therefore can be important influencers of behaviour (Bush, Martin & Bush, 2004). If individuals are aspiring to be like a celebrity role model, they could be more likely to model their behaviours (Singh, Vinnicombe & James, 2006) and in this case, also upload a no make-up selfie and make the donation to Cancer Research UK.Just AskOne of the key ‘weapons’ Cialdini (2000) identifies for influencing behaviour is simply asking for what you want. Research has shown, for example that 56% of females asked by a male stranger would agree to go on a date with him (Clark & Hatfield, 1989). As the #nomakeupselfie posts continued to grow, girls began to nominate three friends within their posts who should do the selfie next (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Like asking strangers on dates, people are more likely to conform to a behaviour when they are asked to do so directly, which could again, be increasing the likelihood of individuals posting no make-up selfies and donating. AttitudesThe British culture is one very heavily influenced by what others think of us. It is no secret we want to be viewed positively by our peers; a view that can be created through giving generously and selflessly (Li, Pickles & Savage, 2005). Compassion and generosity have been rated as two of the most important factors when rating how much we like other peers (Hartley et al, 2016). With these pre-conceived attitudes within the British culture, it is easy to see how so many were influenced to donate to Cancer Research UK; fast to be perceived as generous, selfless and therefore likeable to others. The no-make up selfies were considered both selfless through the donations and brave in uploading a photo in which they were not comfortable uploading, and as stated by Deller and Tilton (2015), selflessness and bravery is rewarded. ConsistencyCialdini (2000) also identifies consistency as one of the weapons in influencing behaviour. This is a phenomenon that states once we have made a stand, particularly in public, we are more likely to act consistent with this behaviour. For example, students were significantly more likely to stick to the estimates they had given for the length of a line when they declared the length publicly, as opposed to privately (Deutch & Gerard, 1955). Once individuals have taken their no-make up selfie and shared it on social media, they have made a public stand for their support for Cancer Research UK, and are therefore more likely to donate to the charity alongside their selfie, hence the £8,000,000 raised alongside the tens of thousands of selfies uploaded (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014).Above are just a select few of the techniques that may have encouraged people to participate in the #nomakeupselfie’s themselves, with others ranging from peer pressure to becoming a ‘killjoy’ for not taking part (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Whatever it was that made people get involved has got charities and marketers hunting it down in in order to become the next fund-raising phenomenon. If we are to take anything away from these viral selfies, realise and remember that behavioural influences can be used for the greater good. Thanks to the posts and donations of bare-faced woman, 10 new clinical trials could be funded, amongst other streams of research (#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered, 2014). A step closer to a cure for cancer has got to be making the world a better place. References#nomakeupselfie – why it worked. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2014/mar/25/nomakeupselfie-viral-campaign-cancer-research#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2014/03/25/nomakeupselfie-some-questions-answered/Bush, A. J., Martin, C. A., & Bush, V. D. (2004). Sports celebrity influence on the behavioral intentions of generation Y. Journal of Advertising Research, 44(01), 108-118.Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Collins.Clark, R. D. & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of psychology and human sexuality, 2, 39-55.Deller, R. A. & Tilton, S. (2015). Selfies as charitable meme: charity and national identity in the #nomakeupselfie and the #thumbsupforstephen campaigns. International journal of communication, 9, 1788-1805. Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The journal of abnormal and social psychology, 51(3), 629.Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them. (2014, March 7). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/mar/07/oscars-selfie-most-retweeted-everHartley, A. G., Furr, R. M., Helzer, E. G., Jayawickreme, E., Velasquez, K. R., & Fleeson, W. (2016). Morality’s centrality to liking, respecting, and understanding others. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1948550616655359.Kelting, K., & Rice, D. H. (2013). Should we hire David Beckham to endorse our brand? Contextual interference and consumer memory for brands in a celebrity’s endorsement portfolio. Psychology & Marketing, 30(7), 602-613.Li, Y., Pickles, A., & Savage, M. (2005). Social capital and social trust in Britain. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 109-123.Michael, A. K., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: the impact on advertising effectiveness and credibility. Journal of advertising, 18, 4-10.Radha, G. & Jija, P. (2013). Influence of celebrity endorsement on the consumer’s purchase decision. International journal of scientific and research publications, 3, 1-28.Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 61(2), 195.Sherif, M. & Sherif, C. W. (1953). Groups in harmony and tension. New York: Harper. Singh, V., Vinnicombe, S., & James, K. (2006). Constructing a professional identity: how young female managers use role models. Women in Management Review, 21(1), 67-81.The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures. (2014, March 19). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/selfie-statistics-2014/497309Theresa Maynia! (2016, October 31). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3891738/Theresa-Maynia-Selfies-autographs-red-carpet-PM-works-crowd-like-true-lister-Pride-Britain-awards.htmlWalgrave, S., & Van Aelst, P. (2006). The contingency of the mass media’s political agenda setting power: toward a preliminary theory. Journal of communication, 56, 88-109.

Figure Three. Left to right: Holly Willoughby’s and Jodie Marsh’s #nomakeupselfieRole ModelsIn addition, celebrities are traditionally seen as attractive and likeable individuals who are considered to be highly influential (Kamins et al, 1989), and therefore can be important influencers of behaviour (Bush, Martin & Bush, 2004). If individuals are aspiring to be like a celebrity role model, they could be more likely to model their behaviours (Singh, Vinnicombe & James, 2006) and in this case, also upload a no make-up selfie and make the donation to Cancer Research UK.Just AskOne of the key ‘weapons’ Cialdini (2000) identifies for influencing behaviour is simply asking for what you want. Research has shown, for example that 56% of females asked by a male stranger would agree to go on a date with him (Clark & Hatfield, 1989). As the #nomakeupselfie posts continued to grow, girls began to nominate three friends within their posts who should do the selfie next (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Like asking strangers on dates, people are more likely to conform to a behaviour when they are asked to do so directly, which could again, be increasing the likelihood of individuals posting no make-up selfies and donating. AttitudesThe British culture is one very heavily influenced by what others think of us. It is no secret we want to be viewed positively by our peers; a view that can be created through giving generously and selflessly (Li, Pickles & Savage, 2005). Compassion and generosity have been rated as two of the most important factors when rating how much we like other peers (Hartley et al, 2016). With these pre-conceived attitudes within the British culture, it is easy to see how so many were influenced to donate to Cancer Research UK; fast to be perceived as generous, selfless and therefore likeable to others. The no-make up selfies were considered both selfless through the donations and brave in uploading a photo in which they were not comfortable uploading, and as stated by Deller and Tilton (2015), selflessness and bravery is rewarded. ConsistencyCialdini (2000) also identifies consistency as one of the weapons in influencing behaviour. This is a phenomenon that states once we have made a stand, particularly in public, we are more likely to act consistent with this behaviour. For example, students were significantly more likely to stick to the estimates they had given for the length of a line when they declared the length publicly, as opposed to privately (Deutch & Gerard, 1955). Once individuals have taken their no-make up selfie and shared it on social media, they have made a public stand for their support for Cancer Research UK, and are therefore more likely to donate to the charity alongside their selfie, hence the £8,000,000 raised alongside the tens of thousands of selfies uploaded (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014).Above are just a select few of the techniques that may have encouraged people to participate in the #nomakeupselfie’s themselves, with others ranging from peer pressure to becoming a ‘killjoy’ for not taking part (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Whatever it was that made people get involved has got charities and marketers hunting it down in in order to become the next fund-raising phenomenon. If we are to take anything away from these viral selfies, realise and remember that behavioural influences can be used for the greater good. Thanks to the posts and donations of bare-faced woman, 10 new clinical trials could be funded, amongst other streams of research (#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered, 2014). A step closer to a cure for cancer has got to be making the world a better place. References#nomakeupselfie – why it worked. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2014/mar/25/nomakeupselfie-viral-campaign-cancer-research#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2014/03/25/nomakeupselfie-some-questions-answered/Bush, A. J., Martin, C. A., & Bush, V. D. (2004). Sports celebrity influence on the behavioral intentions of generation Y. Journal of Advertising Research, 44(01), 108-118.Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Collins.Clark, R. D. & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of psychology and human sexuality, 2, 39-55.Deller, R. A. & Tilton, S. (2015). Selfies as charitable meme: charity and national identity in the #nomakeupselfie and the #thumbsupforstephen campaigns. International journal of communication, 9, 1788-1805. Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The journal of abnormal and social psychology, 51(3), 629.Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them. (2014, March 7). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/mar/07/oscars-selfie-most-retweeted-everHartley, A. G., Furr, R. M., Helzer, E. G., Jayawickreme, E., Velasquez, K. R., & Fleeson, W. (2016). Morality’s centrality to liking, respecting, and understanding others. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1948550616655359.Kelting, K., & Rice, D. H. (2013). Should we hire David Beckham to endorse our brand? Contextual interference and consumer memory for brands in a celebrity’s endorsement portfolio. Psychology & Marketing, 30(7), 602-613.Li, Y., Pickles, A., & Savage, M. (2005). Social capital and social trust in Britain. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 109-123.Michael, A. K., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: the impact on advertising effectiveness and credibility. Journal of advertising, 18, 4-10.Radha, G. & Jija, P. (2013). Influence of celebrity endorsement on the consumer’s purchase decision. International journal of scientific and research publications, 3, 1-28.Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 61(2), 195.Sherif, M. & Sherif, C. W. (1953). Groups in harmony and tension. New York: Harper. Singh, V., Vinnicombe, S., & James, K. (2006). Constructing a professional identity: how young female managers use role models. Women in Management Review, 21(1), 67-81.The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures. (2014, March 19). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/selfie-statistics-2014/497309Theresa Maynia! (2016, October 31). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3891738/Theresa-Maynia-Selfies-autographs-red-carpet-PM-works-crowd-like-true-lister-Pride-Britain-awards.htmlWalgrave, S., & Van Aelst, P. (2006). The contingency of the mass media’s political agenda setting power: toward a preliminary theory. Journal of communication, 56, 88-109.

Nonverbal Behavior and Election Outcomes

By Humintell Director David Matsumoto, Ph.D

By Humintell Director David Matsumoto, Ph.D

“A politician is someone who can tell you to go to hell in a way that makes you look forward to the trip.”

Along my travels around this country and around the world I came along the quote above and it has always stuck in my mind. Now with the crazy 2016 presidential election winding down (or winding up to a frenzy, depending on your point of view), I have been thinking about this quote a lot.

I believe what we have all been witness to in the last few months is truly the power of nonverbal behavior in shaping perceptions, preferences, and opinions. How the presidential candidates behave in terms of their nonverbal demeanor – their facial expressions, tone of voice, gestures, body postures, positioning and interpersonal spacing – all have provided important cues to not only each candidate’s personality, motivations, and intentions, but also to the quality of their interpersonal relationships and the dynamics of that relationship. But while this is true most of the time in general, I believe that these perceptions have come to far outweigh any other factor that may (or should) be considered when making decisions about who to vote for. These other factors, for instance, might include the policies they are advocating for the future, how policies have worked or not in the past, and evidence concerning the candidates’ competence and effectiveness in their positions in the past. Surely, these other factors should also be given consideration in making voting decisions. This election, far more than any other election in recent history, seems to be more about impressions of the personalities of the individual candidates rather than factors such as future intended policies or previous competence or effectiveness. And judgments about the impressions of their personalities is largely driven by nonverbal behavior.

In fact there is a large research literature spanning several decades that has examined the influence of nonverbal behavior on voting preferences, election outcomes, and judgments of trustworthiness and credibility (click HERE for sampling of these studies). These studies have shown that people reliably make judgments of trustworthiness, credibility, and liking from facial expressions, tone of voice, gestures, and overall demeanor and style. Moreover, these judgments have direct effects on voting preferences and election outcomes.

Many politicians know this and surround themselves with consultants who help politicians change or adjust their nonverbal behavior so as to look and sound more credible, trustworthy, and likable than they truly are. And many are very good at that game, especially polished politicians with years or decades of experience. Some politicians also strategically attempt to degrade the perceived trustworthiness, credibility, or suitability for office of their opponents, rather than debate on future policy or past competence or effectiveness. In this election cycle, it sure seems we are inundated with these perceptions, and NOT focusing on issues concerning future directions, policies that work or don’t work, and how exactly life will be better for all of us.

Don’t get me wrong; I am of course a large proponent of the power of nonverbal behavior. But it seems to me that elections, especially this one, should be about more than our impressions of people that may or may not be artificially produced. Perhaps we should spend more time examining what kinds of policies they advocate that would affect positive change, which ones would not, what has been effective in the past, and what has not, over and above the rhetoric. I think the American public deserves that.

Clowns and Masked Fear

Over the last couple of months, there has been a surge in stories about so-called “creepy clowns” prowling the streets. This trend has caused mild panic as schools fear about the effect on children, and even the White House has weighed in.

Terrifyingly, one such clown, with rainbow polka dots and curly blue hair even tried to abduct a small child earlier this month in Concord, CA. This lends some credence to clown-based fears, but there is more to the story than these incidents. What is it about the very nature of clown suited assailants that so deeply troubles the American public?

Humintell’s Dr. David Matsumoto explains that such a disguise “provides de-identification” for possible assailants. This means that, because their faces are obscured by makeup or fake noses, they are difficult to identify. The clown suits, in other words, create a sense of anonymity. This creates fear as anonymity can result in significant behavioral changes.

When individuals are recognizable or unmasked, they are more likely to follow social cues and expectations. As Dr. Matsumoto pointed out, “Identity is a large part of how society regulates behavior.”

This subject has been extensively studied in the field of social psychology, and researchers have found that people wearing masks tend to act more aggressively, self-evaluate less frequently, and eschew social norms of behavior.

Moreover, clown makeup obscures facial expressions, and clowns are infamous for pulling pranks. Factors such as these exacerbate the existing problem that masks and de-individualization create. In fact, clowns compete with the likes of funeral home directors and taxidermists for the “creepiest” profession.

Clowns often even actively take on an identity different than their own. A lot of clowns have their own pseudonyms, calling themselves something like “Mr. Bibbles” instead of their legal names. This feeds into the idea that they are not acting like themselves, which combined with their anonymity, results in a fear that they will act violently, or at least erratically.

But this phenomenon is not just about why we find clowns creepy. Instead, it is about why we find what seems like a movement of clowns especially creepy. Part of the reason is that de-individualization is deeply intertwined with group conformity.

In a classic study, psychologists analyzed the behavior of masked children on Halloween, in order to determine if anonymity led to them committing a minor transgression: stealing extra candy. Almost unsurprisingly, they found that the majority of masked children would help themselves to the candy bowl, especially if other children were doing the same.

Even if the children lost anonymity after being asked for their names and addresses, the majority continued to steal if the first few children did.

This speaks to the fact that large numbers of masked individuals create a homogenized and de-individualized mass with this apparent proclivity for deviant behavior. This is a lot of what inspires fear over these creepy clowns: they are anonymous, and there is a large group of them. Why are there so many? Why must they disguise themselves?

Or perhaps we have all just read too much Stephen King.

Click here to view the embedded video.

For more information on fear, read our blog on detecting fear here and the unexpectedly direct result of terror here.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- …

- 558

- Next Page »