Anyone who knows me personally would know that when it comes to religion and God, I am a huge skeptic. However, by looking at the statistics, it is obvious that a lot of people have been convinced and persuaded by ‘God’s words and teachings’ (Pew Research Center, 2015). Each person has their own personal reason for their belief, however, after a few lectures on persuasion and influence, I soon came to recognise that many of the techniques found to be persuasively successful have also been used by religion. I agree that it would be a tremendous oversimplification to claim that these techniques are the reason behind the spread and acceptance of theology. Nevertheless, I do believe that they have a significant impact on people’s decision to believe in a certain religion.  According to Robert Cialdini, one of the six main principles that are involved when influencing people’s attitudes and behaviour is the Reciprocity Principle. The principle states that humans tend to give back, or reciprocate, the same behaviour that they have received. Therefore, in order to be able to persuade someone to do something for us, we must first do something for them. Once the favour has been done, they would then feel indebted and thus more likely to be persuaded to behave in a certain manner. Further support is provided Garner(2005) who found that participants given a hand written note were more likely to fill in a survey than those asked verbally. According to Cialdini, the effort that had gone through writing a note was recognized by the participant and obligated them into reciprocating that effort. This is why, participants who were provided the hand written note were also found to provide better quality responses. In religion, especially the Abrahamic ones, it is a common belief that most of the things we possess, including our soul and body, were created by the all-powerful God. Now, if I were to believe in God, I could easily see how people would feel indebted and obligated to spend their lives worshipping their creator. The Principle of Commitment and Consistency, which is another of Cialdini’s six core principles, can also be found in the Abrahamic religions. According to this principle, people are more likely to actually do something once they have publicly claimed or promised to do so. Once we make a promise, we feel obliged to fulfill our promise and stay true to our words. In addition, once we have made a decision and committed to something, we try and convince ourselves that we have made the right call by developing new justifications to confirm our decision. One of the most obvious examples of this tactic being used in religion is the sacrament of Confirmation performed in Christianity. The confirmation ritual allows those who have already been baptized to confirm their belief and the promises made on their behalf. Unfortunately, the act of baptism, which is mainly performed at infancy, creates a sense of commitment itself, and many would feel obliged to stay consistent with the decision made on their behalf as a child. In addition, most Catholic churches carry out the ritual around the age of 14, when the child still lacks the intellectual capacity and sufficient knowledge needed to make such a significant judgment. This is one of the reasons why many people, including myself, believe that the notion of theology should not be introduced to a child until much later in their lives. If we were to allow children to live the first 20 years of their lives without the mention of any God or religion, we would be able to provide them with the opportunity to make a well-balanced decision, rather than indoctrinate them and force them down a certain path.Another persuasive tactic, which arguably could be religions’ most effective technique, is providing a sense of belonging. This was actually brought to my attention by an atheist friend who claimed that growing up in a Hindu family, with religious parents and relatives, actually created a sense of alienation for her. The religion, according to her, formed a community for the rest, which she felt left out of. As pointed out in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we are social beings who need to interact and communicate

According to Robert Cialdini, one of the six main principles that are involved when influencing people’s attitudes and behaviour is the Reciprocity Principle. The principle states that humans tend to give back, or reciprocate, the same behaviour that they have received. Therefore, in order to be able to persuade someone to do something for us, we must first do something for them. Once the favour has been done, they would then feel indebted and thus more likely to be persuaded to behave in a certain manner. Further support is provided Garner(2005) who found that participants given a hand written note were more likely to fill in a survey than those asked verbally. According to Cialdini, the effort that had gone through writing a note was recognized by the participant and obligated them into reciprocating that effort. This is why, participants who were provided the hand written note were also found to provide better quality responses. In religion, especially the Abrahamic ones, it is a common belief that most of the things we possess, including our soul and body, were created by the all-powerful God. Now, if I were to believe in God, I could easily see how people would feel indebted and obligated to spend their lives worshipping their creator. The Principle of Commitment and Consistency, which is another of Cialdini’s six core principles, can also be found in the Abrahamic religions. According to this principle, people are more likely to actually do something once they have publicly claimed or promised to do so. Once we make a promise, we feel obliged to fulfill our promise and stay true to our words. In addition, once we have made a decision and committed to something, we try and convince ourselves that we have made the right call by developing new justifications to confirm our decision. One of the most obvious examples of this tactic being used in religion is the sacrament of Confirmation performed in Christianity. The confirmation ritual allows those who have already been baptized to confirm their belief and the promises made on their behalf. Unfortunately, the act of baptism, which is mainly performed at infancy, creates a sense of commitment itself, and many would feel obliged to stay consistent with the decision made on their behalf as a child. In addition, most Catholic churches carry out the ritual around the age of 14, when the child still lacks the intellectual capacity and sufficient knowledge needed to make such a significant judgment. This is one of the reasons why many people, including myself, believe that the notion of theology should not be introduced to a child until much later in their lives. If we were to allow children to live the first 20 years of their lives without the mention of any God or religion, we would be able to provide them with the opportunity to make a well-balanced decision, rather than indoctrinate them and force them down a certain path.Another persuasive tactic, which arguably could be religions’ most effective technique, is providing a sense of belonging. This was actually brought to my attention by an atheist friend who claimed that growing up in a Hindu family, with religious parents and relatives, actually created a sense of alienation for her. The religion, according to her, formed a community for the rest, which she felt left out of. As pointed out in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, we are social beings who need to interact and communicate  with one another. Religion, tactfully, uses this need and merges social interaction and religious rituals together, hence creating a community of people with similar attitudes and beliefs. This, in my opinion, is actually one of the few positive aspects of religion. However, this too can be used as a persuasive tool, especially if a person does not already hold a strong view towards a certain faith. People who are born or move into such communities with different beliefs may begin to feel excluded. In order to be able to feel like they belong, they may begin to partake in some of theses rituals. Eventually, this could create a cognitive dissonance, where one’s attitudes are no longer aligned with their behaviour. However, as mentioned previously, people seek consistency and thus when an inconsistency arises, they begin to try and change something in order to eliminate the dissonance. Many would consider changing their behaviour first, however, unsurprisingly, humans find it more difficult to change their behaviour than their attitude. In our case, their behaviour allows them to interact with the rest of the community and provides them with a sense of belonging. Hence, in most cases, it is our attitudes that are changed to accommodate our behaviour.

with one another. Religion, tactfully, uses this need and merges social interaction and religious rituals together, hence creating a community of people with similar attitudes and beliefs. This, in my opinion, is actually one of the few positive aspects of religion. However, this too can be used as a persuasive tool, especially if a person does not already hold a strong view towards a certain faith. People who are born or move into such communities with different beliefs may begin to feel excluded. In order to be able to feel like they belong, they may begin to partake in some of theses rituals. Eventually, this could create a cognitive dissonance, where one’s attitudes are no longer aligned with their behaviour. However, as mentioned previously, people seek consistency and thus when an inconsistency arises, they begin to try and change something in order to eliminate the dissonance. Many would consider changing their behaviour first, however, unsurprisingly, humans find it more difficult to change their behaviour than their attitude. In our case, their behaviour allows them to interact with the rest of the community and provides them with a sense of belonging. Hence, in most cases, it is our attitudes that are changed to accommodate our behaviour.  The last technique that I will be discussing is the ‘appeal to fear’. Fear appeal is when persuasion is attempted through the presentation of potential risk and an arousal of fear. The stimuli creates a sense of anxiety, which in turn leads to a negative physiological state that compels the body to respond in any way in order to get rid of the threat and decrease the level of distress. If we take a look at Islam and Christianity, we are able to see that their Gods have presented them with similar notions of hell; a place made for the torment and punishment of those who have sinned and disobeyed His laws. By presenting them with an endless fear-evoking stimulus, many people may alter their beliefs and attitudes purely to eradicate the sense of anxiety. As Bertrand Russell points out, “Religion is based primarily and mainly upon fear. It is partly the terror of the unknown and partly the wish to feel that you have a kind of elder brother who will stand by you in all your troubles and disputes. Fear is the basis of the whole thing – fear of the mysterious, fear of defeat, fear of death” (Russell, 1957).As mentioned previously, persuasive techniques may not be the only answer to why religion has been able to spread so vastly, yet it is one of many rational responses. Most of the techniques I have discussed do not refer to logic in any way and instead, they appeal to emotions such as fear and a sense of belonging. Maybe if the ideas proposed were a bit more realistic and consistent, then they would no longer need to scare us into believing; reasoning with us would be enough. ReferencesGarner, R. (2005). Post-It® Note Persuasion: A Sticky Influence. Journal of Consumer Psychology , 15 (3), 230-237. Huitt, W. (2007). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Educational Psychology InteractivePew Research Center. (2015, April 2). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050. Retrieved November 29, 2016, from Pew Research Center: http://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/ Russell, B. (1957). Why I am not a Christian, and other essays on religion and related subjects. New York City, NY: Simon and Schuster.

The last technique that I will be discussing is the ‘appeal to fear’. Fear appeal is when persuasion is attempted through the presentation of potential risk and an arousal of fear. The stimuli creates a sense of anxiety, which in turn leads to a negative physiological state that compels the body to respond in any way in order to get rid of the threat and decrease the level of distress. If we take a look at Islam and Christianity, we are able to see that their Gods have presented them with similar notions of hell; a place made for the torment and punishment of those who have sinned and disobeyed His laws. By presenting them with an endless fear-evoking stimulus, many people may alter their beliefs and attitudes purely to eradicate the sense of anxiety. As Bertrand Russell points out, “Religion is based primarily and mainly upon fear. It is partly the terror of the unknown and partly the wish to feel that you have a kind of elder brother who will stand by you in all your troubles and disputes. Fear is the basis of the whole thing – fear of the mysterious, fear of defeat, fear of death” (Russell, 1957).As mentioned previously, persuasive techniques may not be the only answer to why religion has been able to spread so vastly, yet it is one of many rational responses. Most of the techniques I have discussed do not refer to logic in any way and instead, they appeal to emotions such as fear and a sense of belonging. Maybe if the ideas proposed were a bit more realistic and consistent, then they would no longer need to scare us into believing; reasoning with us would be enough. ReferencesGarner, R. (2005). Post-It® Note Persuasion: A Sticky Influence. Journal of Consumer Psychology , 15 (3), 230-237. Huitt, W. (2007). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Educational Psychology InteractivePew Research Center. (2015, April 2). The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050. Retrieved November 29, 2016, from Pew Research Center: http://www.pewforum.org/2015/04/02/religious-projections-2010-2050/ Russell, B. (1957). Why I am not a Christian, and other essays on religion and related subjects. New York City, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Boohoo are little rascals

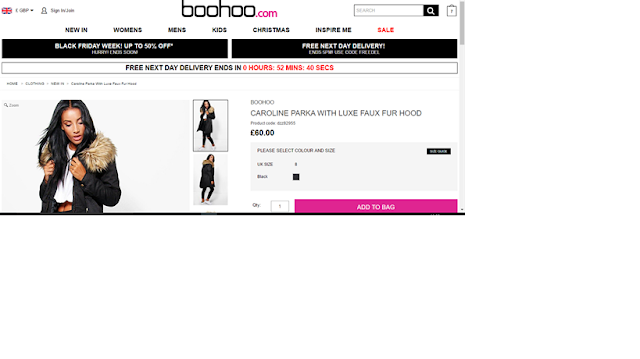

I know what you’re thinking, ANOTHER blog about online shopping…And all I have to say to that is… yes, you are right.Last week, I realised this cold weather is not a joke and the cold air freezing my moisturised hands into shrivelled nanny fingers reminded me that not only do I need gloves, but I need a COAT. And what better time to buy a coat than on, BLACK FRIDAY week(end) yhhhhhhh boiiiiii. So, I went on my usual websites and then ended up on boohoo, and well there is nothing that gets my attention like free food, free parking and FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY, especially when it is written right next to RED CAPITAL WRITING.

So, I went on my usual websites and then ended up on boohoo, and well there is nothing that gets my attention like free food, free parking and FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY, especially when it is written right next to RED CAPITAL WRITING. In my old, dire, non-informed days, this would have made me rush my purchase, feeling as though I need to decide on something quick and that there is no other option but to leave this website having bought something.But with the behaviour change module comes tranquillity (no seriously, that system 1 system 2 lecture made me decide I don’t want to system 1 my life away!). Anywaaaaaaaaaaay, I was feeling such beautiful tranquillity despite the anxiety/stress inducing sales tactic, because I knew that I didn’t need to rush because as I just said, I was aware it was a tactic. Tactics are only used when the opponent has a high chance of losing (Deanne Hay, 2016), so in this case I felt that boohoo are aware they may lose (defined by people visiting their website but not buying anything) so they used this tactic, having it bold at the top of the page but also having the reminder shop with you (left hand side and bottom of the page). They did this to make the customer have to continually and subconsciously make the decision of whether they want to be a part of this offer, again and again and, again – with the hope that they eventually, crumble.

In my old, dire, non-informed days, this would have made me rush my purchase, feeling as though I need to decide on something quick and that there is no other option but to leave this website having bought something.But with the behaviour change module comes tranquillity (no seriously, that system 1 system 2 lecture made me decide I don’t want to system 1 my life away!). Anywaaaaaaaaaaay, I was feeling such beautiful tranquillity despite the anxiety/stress inducing sales tactic, because I knew that I didn’t need to rush because as I just said, I was aware it was a tactic. Tactics are only used when the opponent has a high chance of losing (Deanne Hay, 2016), so in this case I felt that boohoo are aware they may lose (defined by people visiting their website but not buying anything) so they used this tactic, having it bold at the top of the page but also having the reminder shop with you (left hand side and bottom of the page). They did this to make the customer have to continually and subconsciously make the decision of whether they want to be a part of this offer, again and again and, again – with the hope that they eventually, crumble.  But each time I saw the words free next day delivery I didn’t light up with glee like I usually do or think about whether I should divulge in the offer straight away, instead I thought (I MUST WRITE ABOUT THIS). This coat is probably going to last me 4 months, maybe even years and now that I’m a system 2 person, I wasn’t going to rush and decide right now, instead I went on different websites, made lists of everything I liked and kept sieving this list until I reached a small number. However, I nearly fell out of my seat when I went back to boohoo the next day and found…..THIS!

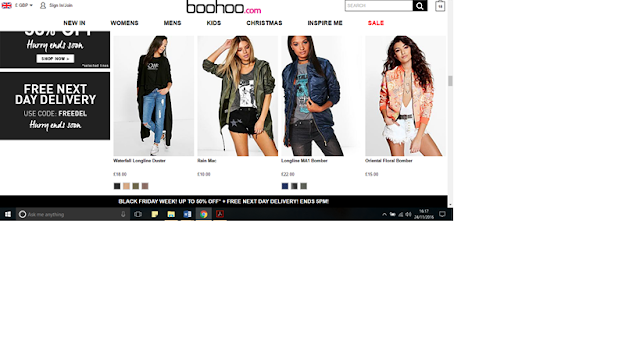

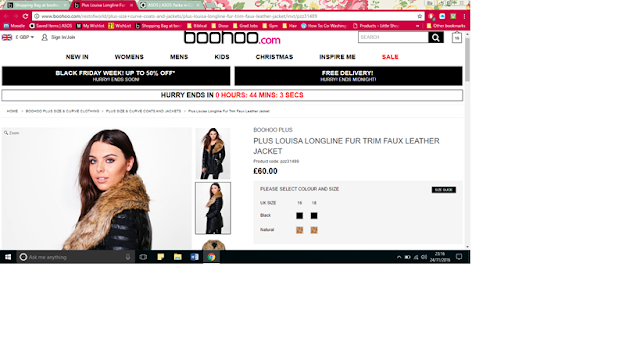

But each time I saw the words free next day delivery I didn’t light up with glee like I usually do or think about whether I should divulge in the offer straight away, instead I thought (I MUST WRITE ABOUT THIS). This coat is probably going to last me 4 months, maybe even years and now that I’m a system 2 person, I wasn’t going to rush and decide right now, instead I went on different websites, made lists of everything I liked and kept sieving this list until I reached a small number. However, I nearly fell out of my seat when I went back to boohoo the next day and found…..THIS! Yet, ANOTHER deal that customers should be hurrying to get.It made me question: does boohoo think I’m stupid? And as each day went by (between my first visit and writing this post) I would check back to their website and there was ALWAYS, something to be in a hurry for, whether it be FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY, FREE STANDARD DELIVERY, NEXT DAY DELIVERY FOR 99P (a discounted price). The psychologists in me knows this isn’t 1) because they want to be genuinely nice to customers and 2) is not an accident or “mistake”Instead it is a very thought out promotional tactic and even has evidence to back its’ effectiveness.System 1 and System 2Although us crazy homo-sapiens are very complex creatures, (yes creatures, I was raised with two older brothers). In the renowned Thinking, Fast and Slow book (Kahneman, 2011) the author put forward the idea that choices that us creatures make, behaviour that we exhibit and well, essentially, everything we think or do is put through/aligned with one of two systems, system 1 (fast and thoughtless) or system 2 (slow and effortful). Take driving for example, when I learnt I was SCARED, I thought WOW my mum said drivers are stupid but here I am having to do and remember so many things at one time, this is so HARD, so the drivers I see MUST be smart. Learning did not come naturally to me, I was not the next Vin Diesel like I thought I would be, instead I was Mrs Mugoo (if you don’t know, get to know). However now that I have held my licence for nearly a year and a half, no one and I mean no one can tell me I’m not the best driver. I know the size of my car (and trust me, this is a big deal because many don’t – oh person driving your little Peugeot why can’t you see that you can fit through the gap????) and I can do many things at once whilst not crashing (I know that isn’t the standard but you get me).BACK to boohoo.When people are, anxious or feel led to be rushed in to something, their following actions tend to be through system 1. For example, without the RED CAPITAL WRITING inducing anxiety, someone may have read FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY and if they were typically a system 1 thinker, they would have been likely to be tempted and buy something. Whereas if said person was typically a system 2 thinker, due to being less likely to feel anxious (no red writing) they would be more likely to effortfully thinking about the offer at hand. Boohoo cleverly induced urgency/anxiety and with reminders plastered all over the website, they made a system 1 environment and hoped for the best, and the fact that this tactic is still being used shows us, it must be working in their favour.Scarcity We want things that a running low, we want things nearly out of stock and we want to get things that are on a limited time frame, this is the crux of the theory of scarcity. Researchers have found empirical evidence for both limited-time scarcity and limited-quantity scarcity, demonstrating their effectiveness in influencing (future and current) customers, (Aggarwal, Jun& Huh, 2011). Parker (2011) did an experimental study on scarcity based in a simulated store, participants were asked to explain their choices from the store and the study found that people significantly selected more scarce items than those which had plenty in stock (see figure from study below).

Yet, ANOTHER deal that customers should be hurrying to get.It made me question: does boohoo think I’m stupid? And as each day went by (between my first visit and writing this post) I would check back to their website and there was ALWAYS, something to be in a hurry for, whether it be FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY, FREE STANDARD DELIVERY, NEXT DAY DELIVERY FOR 99P (a discounted price). The psychologists in me knows this isn’t 1) because they want to be genuinely nice to customers and 2) is not an accident or “mistake”Instead it is a very thought out promotional tactic and even has evidence to back its’ effectiveness.System 1 and System 2Although us crazy homo-sapiens are very complex creatures, (yes creatures, I was raised with two older brothers). In the renowned Thinking, Fast and Slow book (Kahneman, 2011) the author put forward the idea that choices that us creatures make, behaviour that we exhibit and well, essentially, everything we think or do is put through/aligned with one of two systems, system 1 (fast and thoughtless) or system 2 (slow and effortful). Take driving for example, when I learnt I was SCARED, I thought WOW my mum said drivers are stupid but here I am having to do and remember so many things at one time, this is so HARD, so the drivers I see MUST be smart. Learning did not come naturally to me, I was not the next Vin Diesel like I thought I would be, instead I was Mrs Mugoo (if you don’t know, get to know). However now that I have held my licence for nearly a year and a half, no one and I mean no one can tell me I’m not the best driver. I know the size of my car (and trust me, this is a big deal because many don’t – oh person driving your little Peugeot why can’t you see that you can fit through the gap????) and I can do many things at once whilst not crashing (I know that isn’t the standard but you get me).BACK to boohoo.When people are, anxious or feel led to be rushed in to something, their following actions tend to be through system 1. For example, without the RED CAPITAL WRITING inducing anxiety, someone may have read FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY and if they were typically a system 1 thinker, they would have been likely to be tempted and buy something. Whereas if said person was typically a system 2 thinker, due to being less likely to feel anxious (no red writing) they would be more likely to effortfully thinking about the offer at hand. Boohoo cleverly induced urgency/anxiety and with reminders plastered all over the website, they made a system 1 environment and hoped for the best, and the fact that this tactic is still being used shows us, it must be working in their favour.Scarcity We want things that a running low, we want things nearly out of stock and we want to get things that are on a limited time frame, this is the crux of the theory of scarcity. Researchers have found empirical evidence for both limited-time scarcity and limited-quantity scarcity, demonstrating their effectiveness in influencing (future and current) customers, (Aggarwal, Jun& Huh, 2011). Parker (2011) did an experimental study on scarcity based in a simulated store, participants were asked to explain their choices from the store and the study found that people significantly selected more scarce items than those which had plenty in stock (see figure from study below).  Although the above study is done on limited quantity and that research has found limited-quantity to be slightly more effective (i.e. boohoo saying they can only offer 500 people FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY and then having a live status of that), limited time like explained earlier is also effective.The reasoning why scarcity of both kinds are so effective is because we tend to attach more value to things when we know other people are competing for (http://www.referralcandy.com/blog/hurry-stocks-last-13-examples-scarcity-principle-used-marketing/). Even though there wasn’t a limited amount, customers could have felt as though they were in a speed buying competition and that winning this competition would be defined as having an online shopping cart ready before the deal in the countdown ends. When engaging in this competition the customer is likely to add more value to it and want these items more than ever – even if they only came to the website to browse (this is why losing EBay bids is so distressing, when you lose, that added value asks you how on earth will you live without this item in your life).This phenomenon is a part of social proof. Although boohoo doesn’t let you explicitly see other people’s buying habits (like Misguided), customers may feel as though other logical people like themselves would have lapped up the chance of FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY and that they should too, acting as a trigger for this speed buying competition to begin.Mere ExposureBoohoo’s mere exposure was not exposure of an item as typically used by other brands but instead their FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY, as Boohoo were aware that if they could “sell” this to customers then they can rope in other profits with it. As seen by the three pictures taken from Boohoo’s website, FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY and HURRY were not words that a customer could escape, even if consciously ignoring it their subconscious would see it each time. Constantly seeing this offer could tempt many customers, as researchers have found that mere exposure (through banner ads) induces liking (Fang, 2007). Other research found that whatever we are exposed to on a more frequent basis is deemed more favourable compared to things that we barely see. Zajonc (1968) studied differential exposure to faces for “visual memory” and then asked participants what they thought of the man they saw. When assessing the manipulation of the differential exposure to Chinese characters they were then asked how good they think the meaning of the character might be. The study found that exposure effects: those which were exposed more frequently were rated to have a good character meaning more often than those who had a low frequency of exposure.

Although the above study is done on limited quantity and that research has found limited-quantity to be slightly more effective (i.e. boohoo saying they can only offer 500 people FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY and then having a live status of that), limited time like explained earlier is also effective.The reasoning why scarcity of both kinds are so effective is because we tend to attach more value to things when we know other people are competing for (http://www.referralcandy.com/blog/hurry-stocks-last-13-examples-scarcity-principle-used-marketing/). Even though there wasn’t a limited amount, customers could have felt as though they were in a speed buying competition and that winning this competition would be defined as having an online shopping cart ready before the deal in the countdown ends. When engaging in this competition the customer is likely to add more value to it and want these items more than ever – even if they only came to the website to browse (this is why losing EBay bids is so distressing, when you lose, that added value asks you how on earth will you live without this item in your life).This phenomenon is a part of social proof. Although boohoo doesn’t let you explicitly see other people’s buying habits (like Misguided), customers may feel as though other logical people like themselves would have lapped up the chance of FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY and that they should too, acting as a trigger for this speed buying competition to begin.Mere ExposureBoohoo’s mere exposure was not exposure of an item as typically used by other brands but instead their FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY, as Boohoo were aware that if they could “sell” this to customers then they can rope in other profits with it. As seen by the three pictures taken from Boohoo’s website, FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY and HURRY were not words that a customer could escape, even if consciously ignoring it their subconscious would see it each time. Constantly seeing this offer could tempt many customers, as researchers have found that mere exposure (through banner ads) induces liking (Fang, 2007). Other research found that whatever we are exposed to on a more frequent basis is deemed more favourable compared to things that we barely see. Zajonc (1968) studied differential exposure to faces for “visual memory” and then asked participants what they thought of the man they saw. When assessing the manipulation of the differential exposure to Chinese characters they were then asked how good they think the meaning of the character might be. The study found that exposure effects: those which were exposed more frequently were rated to have a good character meaning more often than those who had a low frequency of exposure.  These effects can be applied to retail and customer behaviour too. As based on the findings of Zajonc’s study, being exposed to the FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY so frequently was likely to imply to customers that this FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY is an absolute necessity, whereas if they only saw it once when they first visited the page and then never again, they may have been able to think about it in a system 2 manner and not attribute it as a necessity until after this effortful thought. (If you wondering if I ended up using this FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY, yes, I did, two days after. However, this wasn’t due to their techniques but instead because I had items in my wish list prior to visiting their website.)So how do you feel now? Ready to take on this online shopping world and not be a fool to their money-making schemes?I sure AM! ReferencesAggarwal, P., Jun, S. Y., & Huh, J. H. (2011). Scarcity messages. Journal of Advertising, 40, 19-30.Fang, X., Singh, S., & Ahluwalia, R. (2007). An examination of different explanations for the mere exposure effect. Journal of consumer research, 34, 97-103.Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.Parker, J. R., & Lehmann, D. R. (2011). When shelf-based scarcity impacts consumer preferences. Journal of Retailing, 87, 142-155.Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9, 1.

These effects can be applied to retail and customer behaviour too. As based on the findings of Zajonc’s study, being exposed to the FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY so frequently was likely to imply to customers that this FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY is an absolute necessity, whereas if they only saw it once when they first visited the page and then never again, they may have been able to think about it in a system 2 manner and not attribute it as a necessity until after this effortful thought. (If you wondering if I ended up using this FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY, yes, I did, two days after. However, this wasn’t due to their techniques but instead because I had items in my wish list prior to visiting their website.)So how do you feel now? Ready to take on this online shopping world and not be a fool to their money-making schemes?I sure AM! ReferencesAggarwal, P., Jun, S. Y., & Huh, J. H. (2011). Scarcity messages. Journal of Advertising, 40, 19-30.Fang, X., Singh, S., & Ahluwalia, R. (2007). An examination of different explanations for the mere exposure effect. Journal of consumer research, 34, 97-103.Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.Parker, J. R., & Lehmann, D. R. (2011). When shelf-based scarcity impacts consumer preferences. Journal of Retailing, 87, 142-155.Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9, 1.

Why do I have so many coupons in my wallet?

One day, I just realized that I have many coupons in my wallet. Why do they make this kind of coupons? Why do they spend time and money for making regular customers? Let’s think about our own experiences. Have you ever regret to order a new menu in a restaurant? Have you ever regret to change your job? These kinds of experiences can be explained by the ‘status quo bias’.Samuelson & Zeckhause (1988) first proposed the term ‘status quo bias’. They defined ‘Status quo bias’ as an evident when people prefer things to stay the same by doing nothing or by sticking with a decision made previously. This means that people do not like to take a risk for trying something new, but instead they prefer to sick with a decision made previously. That’s why people tend to choose the same menu in a restaurant. They used a questionnaire in which subjects faced a series of decision problems which were alternately framed to be with and without pre-existing status quo position. They found that subjects tended to remain with the status quo when such a position was offered to the,m. This idea is basically related to loss aversion. (Tversky & Kahneman, 1991). People try to make decisions which avoid the risk rather than decisions that maximize the profit.This idea also can explain the reason why customers have high brand loyalty. This is why many firms try to target children. If a person became a regular customer for a brand they tend to continue their brand loyalty until they die. The marketing which is trying to prevent customers to go to other places is called ‘CRM marketing (Customer Relationship Management Marketing’ or ‘loyalty marketing’.We can find these examples from everyday life as the photo shows.References:Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of risk and uncertainty, 1(1), 7-59.Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. The quarterly journal of economics, 1039-1061.

One day, I just realized that I have many coupons in my wallet. Why do they make this kind of coupons? Why do they spend time and money for making regular customers? Let’s think about our own experiences. Have you ever regret to order a new menu in a restaurant? Have you ever regret to change your job? These kinds of experiences can be explained by the ‘status quo bias’.Samuelson & Zeckhause (1988) first proposed the term ‘status quo bias’. They defined ‘Status quo bias’ as an evident when people prefer things to stay the same by doing nothing or by sticking with a decision made previously. This means that people do not like to take a risk for trying something new, but instead they prefer to sick with a decision made previously. That’s why people tend to choose the same menu in a restaurant. They used a questionnaire in which subjects faced a series of decision problems which were alternately framed to be with and without pre-existing status quo position. They found that subjects tended to remain with the status quo when such a position was offered to the,m. This idea is basically related to loss aversion. (Tversky & Kahneman, 1991). People try to make decisions which avoid the risk rather than decisions that maximize the profit.This idea also can explain the reason why customers have high brand loyalty. This is why many firms try to target children. If a person became a regular customer for a brand they tend to continue their brand loyalty until they die. The marketing which is trying to prevent customers to go to other places is called ‘CRM marketing (Customer Relationship Management Marketing’ or ‘loyalty marketing’.We can find these examples from everyday life as the photo shows.References:Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of risk and uncertainty, 1(1), 7-59.Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. The quarterly journal of economics, 1039-1061.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- …

- 562

- Next Page »