Stevie Wonder’s hit song “Superstition” exemplifies the presence of superstitions even in an era where science and logic dominates the pursuit for knowledge.The Cambridge dictionary online (2016) defines superstition as a “belief that is not based on human reason or scientific knowledge, but is connected with old ideas about magic”, which allows a wide range of beliefs and practices to fall under this term. Examples include fortune telling, folklore, horoscope, witchcraft and luck-related rituals, all of which are still being practiced today. Beck and Forstmeier (2007) proposed that superstition is born from the adaptive associative learning style of identifying patterns and attempts to explain them. This has been proposed to not only apply to humans but animals as well. Skinner (1948) found that after a period of time, pigeons would perform specific movements when they had been put in a cage with a food hopper that presents food at regular intervals. The pigeons happened to be performing a specific behavior when the food hopper appeared, thus linking that behavior with presentation of food although food was given independent of their behavior. As a result, they repeat the behavior whenever they want food (operant conditioning) due to the representativeness heuristic causing perceived causality between the behavior and food (classical conditioning).This behavior is reflective of many superstitious acts in humans. For example, the customary practice of saying “God bless you” or variations of the phrase following a sneeze which originated from the Middle Ages. Pope Gregory VII was said to have used it as a short prayer against diseases during times of the Great Plague in Europe (Kavka, 1983). The effectiveness of the phrase in warding off diseases is definitely questionable with at least a third of the European population being wiped out by the plague (Benedictow, 2004). However, the practice has been normalised today even though most people using it may not know of the phrase’s function.One possible reason why superstitious acts persist in current society is the effect of performing such acts on the perceived self-efficacy of the person. Damisch, Stoberock and Mussweiler (2010) conducted a series of experiments to test the interaction between superstition, performance and self-efficacy. They found that those who had a lucky charm with them did better at a memory task (Figure 1) as well as reported higher levels of self-efficacy at the task (Figure 2) than those who did not. A follow up experiment showed that this increase in self-efficacy improves performance by increasing task persistence (Figure 3).  Figure 1. Mean performance on memory task for participants with and without lucky charms.

Figure 1. Mean performance on memory task for participants with and without lucky charms. Figure 2. Mean self-efficacy ratings reported by participants with and without lucky charms.

Figure 2. Mean self-efficacy ratings reported by participants with and without lucky charms. Figure 3. Mean time spent by participants with and without lucky charms on anagram task.The results of Damisch et al.’s (2010) study can be fit into the Theory of Planned Behavior (Figure 4) in explaining how superstitions affect behaviors and attitudes (Ajzen, 1985). Indulging in superstitious acts causes an increase in self-efficacy which results in stronger intentions to do well in a specific task. The strengthened intentions then increases persistent behavior, indirectly increasing task performance. This phenomena causes superstitious people to make an illusory correlation or causality between superstitious acts and their performance, further reinforcing the behavior and increasing the likelihood of displaying such acts.

Figure 3. Mean time spent by participants with and without lucky charms on anagram task.The results of Damisch et al.’s (2010) study can be fit into the Theory of Planned Behavior (Figure 4) in explaining how superstitions affect behaviors and attitudes (Ajzen, 1985). Indulging in superstitious acts causes an increase in self-efficacy which results in stronger intentions to do well in a specific task. The strengthened intentions then increases persistent behavior, indirectly increasing task performance. This phenomena causes superstitious people to make an illusory correlation or causality between superstitious acts and their performance, further reinforcing the behavior and increasing the likelihood of displaying such acts. Figure 4. Schematic diagram of the Theory of Planned Behavior.Now that we are informed of the way superstition persists, does it mean effort should be directed into breaking them? While superstitions are not logical nor cause their intended effect directly, perhaps they should be left alone simply because they do improve performance. Michael Jordan himself always wore his old University of North Carolina shorts during games even if he had to wear them underneath his official uniform, and that did not stop him from becoming one of the best basketball players in the world. Perhaps when you “believe in things that you don’t understand” you may not suffer but instead succeed. ReferenceAjzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In Action control (pp. 11-39). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.Beck, J., & Forstmeier, W. (2007). Superstition and belief as inevitable by-products of an adaptive learning strategy. Human Nature, 18, 35-46.Benedictow, O. J. (2004). The medieval demographic system. In The Black Death, 1346-1353: the complete history (pp. 245-256). Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.Cambridge dictionaries online. (2016). Retrieved from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/Damisch, L., Stoberock, B., & Mussweiler, T. (2010). Keep your fingers crossed! How superstition improves performance. Psychological Science, 21, 1014-1020.Kavka, S. J. (1983). The sneeze—blissful or baneful?. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 249, 2304-2305.Skinner, B. F. (1948). ‘Superstition’in the pigeon. Journal of experimental psychology, 38, 168-172.

Figure 4. Schematic diagram of the Theory of Planned Behavior.Now that we are informed of the way superstition persists, does it mean effort should be directed into breaking them? While superstitions are not logical nor cause their intended effect directly, perhaps they should be left alone simply because they do improve performance. Michael Jordan himself always wore his old University of North Carolina shorts during games even if he had to wear them underneath his official uniform, and that did not stop him from becoming one of the best basketball players in the world. Perhaps when you “believe in things that you don’t understand” you may not suffer but instead succeed. ReferenceAjzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In Action control (pp. 11-39). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.Beck, J., & Forstmeier, W. (2007). Superstition and belief as inevitable by-products of an adaptive learning strategy. Human Nature, 18, 35-46.Benedictow, O. J. (2004). The medieval demographic system. In The Black Death, 1346-1353: the complete history (pp. 245-256). Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer.Cambridge dictionaries online. (2016). Retrieved from http://dictionary.cambridge.org/Damisch, L., Stoberock, B., & Mussweiler, T. (2010). Keep your fingers crossed! How superstition improves performance. Psychological Science, 21, 1014-1020.Kavka, S. J. (1983). The sneeze—blissful or baneful?. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 249, 2304-2305.Skinner, B. F. (1948). ‘Superstition’in the pigeon. Journal of experimental psychology, 38, 168-172.

Climate change: The inconvenient truth

We are facing the next major extinction since the dinosaurs. Scientists have forewarned that a mere 2- degree Celsius rise in temperature on Earth could predict perilous implications such as drought, famine and human conflict. Countries will be underwater due to sea levels rising, and such high levels of drought means an inability to feed populations, generating mass migration or invasion of other countries. Not only are we rapidly approaching this 2- degree danger zone, but we will easily exceed it. A further 7- degree Celsius raise in temperature has the potential to trigger a similar effect which turned Venus into a 460- degree Celsius inhabitable environment. With such alarming warnings from scientists and researchers, it is our responsibility to protect our planet. Figure 1. Cowspiracy filmmakers Kip Anderson (right) andKeegan Kuhn (left)Environmental companies and activists have programmed society to believe the overuse of fossil fuels is the catalyst for climate change. The oil and gas industry is plastered over news and social media sites to be the most damaging environmental practise by humanity. Yet a ground- breaking independent documentary film, Cowspiracy, has exposed the sustainability secrets many environmental agencies have actively avoided. The filmmakers, Kip Anderson and Keegan Kuhn, uncovered an arguably intentional refusal to address the principle yet unforeseen cause of global warming: animal agriculture.Raising livestock produces more dangerous emissions than the entire transportation sector. Consequently, more greenhouse gases are produced from animal agriculture than from the exhausts of all cars, trucks, trains, boats and planes combined. On top of this, methane produced from cattle is 86x more destructive than carbon dioxide. Yet websites of the largest environmental agencies in America have almost no information on the detrimental effects of animal agriculture. The gateway belief model can be greatly applied to such scientific communication. When faced with uncertainty individuals tend to turn to experts for guidance, such as environmental agencies. This guidance is viewed as a consensus, and thus regarded as correct. Therefore, if fossil fuels are noted as the most damaging cause of climate change; the public will believe this as factual. The model also explains that if organisations portrayed animal agriculture as the leading issue, individual perceptions will follow, leading to a greater impact to reduce global warming. In summary, if environmental organisations portrayed animal agriculture as the primary cause of climate change, the public will comply to reduce the effects of greenhouse gases, deforestation and global warming. Agencies simply need to address the impact of animal agriculture. So why haven’t they?

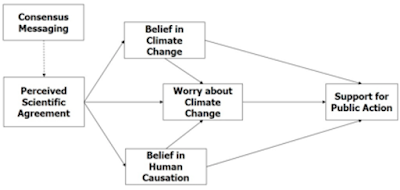

Figure 1. Cowspiracy filmmakers Kip Anderson (right) andKeegan Kuhn (left)Environmental companies and activists have programmed society to believe the overuse of fossil fuels is the catalyst for climate change. The oil and gas industry is plastered over news and social media sites to be the most damaging environmental practise by humanity. Yet a ground- breaking independent documentary film, Cowspiracy, has exposed the sustainability secrets many environmental agencies have actively avoided. The filmmakers, Kip Anderson and Keegan Kuhn, uncovered an arguably intentional refusal to address the principle yet unforeseen cause of global warming: animal agriculture.Raising livestock produces more dangerous emissions than the entire transportation sector. Consequently, more greenhouse gases are produced from animal agriculture than from the exhausts of all cars, trucks, trains, boats and planes combined. On top of this, methane produced from cattle is 86x more destructive than carbon dioxide. Yet websites of the largest environmental agencies in America have almost no information on the detrimental effects of animal agriculture. The gateway belief model can be greatly applied to such scientific communication. When faced with uncertainty individuals tend to turn to experts for guidance, such as environmental agencies. This guidance is viewed as a consensus, and thus regarded as correct. Therefore, if fossil fuels are noted as the most damaging cause of climate change; the public will believe this as factual. The model also explains that if organisations portrayed animal agriculture as the leading issue, individual perceptions will follow, leading to a greater impact to reduce global warming. In summary, if environmental organisations portrayed animal agriculture as the primary cause of climate change, the public will comply to reduce the effects of greenhouse gases, deforestation and global warming. Agencies simply need to address the impact of animal agriculture. So why haven’t they? Figure 2. The gateway belief model demonstrating the pathway for acceptance of climate change.The simple suggestion would be to promote veganism and condense meat production. Yet recent statistics show that only 2% of the UK population and 0.5% of the USA population are vegans. To promote the reduction of meat consumption would impact over 95% of the population, and as such seems an unlikely request from environmental charities. These organisations are businesses, who need to ensure a reliable source of funding. Greenpeace is the largest environmental agency with an estimated $360 million global empire. For this reason, the public is advised to occasionally change their daily routine, for example through recycling and driving less, so they are lead to believe they are helping the environment. Whilst to some extent this is true, they are ignoring the primary cause of global warming. Agencies know that turning vegetarian or vegan is less achievable. Therefore, to sustain donations and interest from the public, animal agriculture is discounted and climate change is attributed to less demanding tasks, such as saving water and recycling plastic.

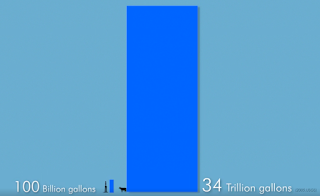

Figure 2. The gateway belief model demonstrating the pathway for acceptance of climate change.The simple suggestion would be to promote veganism and condense meat production. Yet recent statistics show that only 2% of the UK population and 0.5% of the USA population are vegans. To promote the reduction of meat consumption would impact over 95% of the population, and as such seems an unlikely request from environmental charities. These organisations are businesses, who need to ensure a reliable source of funding. Greenpeace is the largest environmental agency with an estimated $360 million global empire. For this reason, the public is advised to occasionally change their daily routine, for example through recycling and driving less, so they are lead to believe they are helping the environment. Whilst to some extent this is true, they are ignoring the primary cause of global warming. Agencies know that turning vegetarian or vegan is less achievable. Therefore, to sustain donations and interest from the public, animal agriculture is discounted and climate change is attributed to less demanding tasks, such as saving water and recycling plastic. Figure 3. The proportional representation of gallons of water used for hydraulic fracking (left) compared to animal agriculture (right) per year in AmericaWhilst climate change is still overlooked by many, our rapidly overcrowded planet must remain sustainable. Leaving the shower on constantly for two months is the equivalent to making one hamburger. Cowspiracy was able to uncover the controversial truth about the damaging effects of animal agriculture, leading to the film backing and funding being dropped. In the last 20 years in Brazil, where deforestation has resulted in an acre of land being cut down every six seconds, 2,100 activists have been killed trying to unravel these sustainability secrets. Animal agriculture is the primary cause of climate change, and whilst environmental agencies have concealed this factor to keep public interest, it must be addressed in order to avert the effects of global warming.References: Van der Linden, S. L., Leiserowitz, A. A., Feinberg, G. D., & Maibach, E. W. (2015). The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: experimental evidence. Plos One, 10(2), e0118489.

Figure 3. The proportional representation of gallons of water used for hydraulic fracking (left) compared to animal agriculture (right) per year in AmericaWhilst climate change is still overlooked by many, our rapidly overcrowded planet must remain sustainable. Leaving the shower on constantly for two months is the equivalent to making one hamburger. Cowspiracy was able to uncover the controversial truth about the damaging effects of animal agriculture, leading to the film backing and funding being dropped. In the last 20 years in Brazil, where deforestation has resulted in an acre of land being cut down every six seconds, 2,100 activists have been killed trying to unravel these sustainability secrets. Animal agriculture is the primary cause of climate change, and whilst environmental agencies have concealed this factor to keep public interest, it must be addressed in order to avert the effects of global warming.References: Van der Linden, S. L., Leiserowitz, A. A., Feinberg, G. D., & Maibach, E. W. (2015). The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: experimental evidence. Plos One, 10(2), e0118489.

The Bristol Zoo parking attendant

If you are from Bristol or have any friends or family, you will have probably heard about the Bristol Zoo attendant and his cunning scheme to make money, through exploiting the norms of the people around, and obedience to authority.

If you are from Bristol or have any friends or family, you will have probably heard about the Bristol Zoo attendant and his cunning scheme to make money, through exploiting the norms of the people around, and obedience to authority.  Whether this is a true story or not is debatable, however, many people still talk about it, and it got me thinking about how this could be done anywhere and be successful.Bristol Zoo is one of many attractions in Bristol, homing animals of many species and sizes, from Jock the silverback to small insects and bugs. A lovely day out for anyone! There is a car park right outside of the Zoo which gets filled promptly, or an overflow carpark in peak times which is situated on ‘The Downs’, a large greenery area of land sitting in the middle of the City (right next to the Zoo). Story has it, that a very clever man in his 50’s put on a uniform resembling a parking attendant, got himself some equipment that enabled him to print tickets on the spot and walked around the car park, collecting money from visitors and accrediting them a ticket in return. You can imagine just how much this man would have received in a day, charging a few pounds per day for hundreds of cars coming and going. Until one day.. He wasn’t there, anxious visitors asking workers at the Zoo, where to pay for a ticket so they wouldn’t get a fine. They had no idea of course, where their ticket man had gone and why he had not showed up for work! So the workers at Bristol Zoo rang up Bristol City Council and enquired into why their worker (employed by the council) hadn’t showed up, or why they hadn’t sent a replacement. They replied that they do not organise the workers for the carpark at the Zoo and had no records of anyone working for them. Reality struck when they had realised that a stranger had (for about 10 years) been manipulating the system and collecting money for himself. Now he had disappeared and no record of him anyway, he would probably be as far away from the Zoo as possible, with an enormous wad of cash!The aspects of this tale that strike me the most is obedience to authority. Every single person who parked in that car park gave this man money because he had simply placed a uniform on that resembled an authority figure. He looked right, had the appropriate equipment and a name badge. Why would anyone question his authority? In addition, the social norms people have about obedience to authority, and having to pay for parking meant that everyone followed the crowd in a way. After parking in a space, most drivers probably looked around and saw a man who was approached by other likeminded people, taking their money and given a ticket in response. If anyone questioned what the appropriate behaviour was, they would look for social proof and engage in the behaviours of other people around them. Moreover, visitors are probably preoccupied with the fear of getting a parking ticket, or the stress of controlling their excited children, that contributes to the success this man had. Zimbardo (1973) conducted a very famous Standford prison experiment that demonstrated the power of obedience to authority. By assigning two groups of people randomly to the position of a guard or prisoner, and by having the prison officers wear uniform, this created a sense of power between the two groups, and prisoners as a result of social norms would comply with their requests, (similar to visitors to Bristol zoo, complying with rules and abiding with the social norms.)Other experiments have demonstrated that the power of uniform can affect peoples decisions. Bickman (1971) found people were more likely to comply with individuals who were in a uniform, and the type of uniform also influenced how people conformed. In the case of the Bristol Zoo attendant, the uniform he was dressed in created a sense of authority and people would naturally comply accordingly. References:Bickman, L. (1971). The effect of different uniforms on obedience in field situations. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association.Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Reviews, 9(1-17).

Whether this is a true story or not is debatable, however, many people still talk about it, and it got me thinking about how this could be done anywhere and be successful.Bristol Zoo is one of many attractions in Bristol, homing animals of many species and sizes, from Jock the silverback to small insects and bugs. A lovely day out for anyone! There is a car park right outside of the Zoo which gets filled promptly, or an overflow carpark in peak times which is situated on ‘The Downs’, a large greenery area of land sitting in the middle of the City (right next to the Zoo). Story has it, that a very clever man in his 50’s put on a uniform resembling a parking attendant, got himself some equipment that enabled him to print tickets on the spot and walked around the car park, collecting money from visitors and accrediting them a ticket in return. You can imagine just how much this man would have received in a day, charging a few pounds per day for hundreds of cars coming and going. Until one day.. He wasn’t there, anxious visitors asking workers at the Zoo, where to pay for a ticket so they wouldn’t get a fine. They had no idea of course, where their ticket man had gone and why he had not showed up for work! So the workers at Bristol Zoo rang up Bristol City Council and enquired into why their worker (employed by the council) hadn’t showed up, or why they hadn’t sent a replacement. They replied that they do not organise the workers for the carpark at the Zoo and had no records of anyone working for them. Reality struck when they had realised that a stranger had (for about 10 years) been manipulating the system and collecting money for himself. Now he had disappeared and no record of him anyway, he would probably be as far away from the Zoo as possible, with an enormous wad of cash!The aspects of this tale that strike me the most is obedience to authority. Every single person who parked in that car park gave this man money because he had simply placed a uniform on that resembled an authority figure. He looked right, had the appropriate equipment and a name badge. Why would anyone question his authority? In addition, the social norms people have about obedience to authority, and having to pay for parking meant that everyone followed the crowd in a way. After parking in a space, most drivers probably looked around and saw a man who was approached by other likeminded people, taking their money and given a ticket in response. If anyone questioned what the appropriate behaviour was, they would look for social proof and engage in the behaviours of other people around them. Moreover, visitors are probably preoccupied with the fear of getting a parking ticket, or the stress of controlling their excited children, that contributes to the success this man had. Zimbardo (1973) conducted a very famous Standford prison experiment that demonstrated the power of obedience to authority. By assigning two groups of people randomly to the position of a guard or prisoner, and by having the prison officers wear uniform, this created a sense of power between the two groups, and prisoners as a result of social norms would comply with their requests, (similar to visitors to Bristol zoo, complying with rules and abiding with the social norms.)Other experiments have demonstrated that the power of uniform can affect peoples decisions. Bickman (1971) found people were more likely to comply with individuals who were in a uniform, and the type of uniform also influenced how people conformed. In the case of the Bristol Zoo attendant, the uniform he was dressed in created a sense of authority and people would naturally comply accordingly. References:Bickman, L. (1971). The effect of different uniforms on obedience in field situations. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association.Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Reviews, 9(1-17).

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- …

- 562

- Next Page »