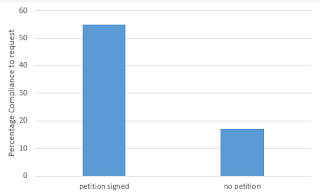

I’m somebody who generally goes about social interaction in a very natural way; I don’t think too much about my word choice or persuasive techniques. Because of this, I am always fascinated by people who are different from me in this way, people who regularly calculate their interaction and use every conversation to their advantage. I have a good friend who does just this. They work in commission only sales and they’re damn good at it. I recently asked them to write down some of the techniques or phrases they use most commonly, and I have to say I was surprised by how many of them I could apply theoretical content to.Giving them the factsObviously whenever you buy anything, you want the facts. You want to know what your options are and what the benefits of each are. All salespeople will do this. But, without being aware of the theory behind its effectiveness, most salespeople will tell you what the most popular option is. This might be the actual best seller, or it might be the item they’re currently trying to increase the sales of. When we look at this theoretically, we can refer to Azjen’s (1985) Theory of Planned Behaviour. Being told the ‘most popular’ choice can influence behaviour through subjective norms, we come to believe that owning that specific product is seen favourable by other people. Another way to look at it is social proof. We evaluate the information to believe that other people have looked at the options and made the decision that it is the best product. Building rapport and gaining information “Never underestimate the power of making someone like you, but keep it focused. Use it to gather knowledge about the person so you can make the sale personal”.Through building rapport with a customer, salespeople are able to have open conversations with you about your needs as a customer. Gathering this information is much easier if they have a natural conversation with you rather than interrogating you about whether you need the highest processing speed on your new laptop or the additional engine power in your car. The majority of the time, you won’t know the answers to these questions anyway, and by learning about you as a customer the salesperson can assess your needs, sell you the product best suited to you, and therefore present the most convincing pitch possible. A salesperson (or a good one at least) will constantly bring back the topic of conversation to how your personality and lifestyle relate to your choice of product. “Oh you enjoy… You will definitely benefit from this upgrade”. Even better, they might ask you questions based on your lifestyle so that you as the customer are convincing yourself that you need the product. “Oh you enjoy… Does that mean you’ll need a product with this feature or that function?”. We can look at the success of the above conversations with regard to the foot-in-the-door technique. This technique refers to the increased likelihood of a person making a large commitment if they have first made smaller commitments to the same thing. This effectiveness of this simple method has been supported by many difference pieces of research an example of which is Freedman and Fraser (1966). In this research, individuals were asked to sign a petition for safe driving. A couple of weeks later the same people were asked to place a large and unattractive sign in their front garden that read “Drive Carefully”. Compliance with the request to put the large sign up increase from 17% (not asked to sign a petition) to 55% (foot-in-the-door condition). In terms of being sold an item, asking you questions such as “do you tend to take a lot of pictures on your phone” may serve as a good way to gain incremental commitment from a customer and, eventually lead them to buy a more expensive phone with a better camera.  Figure one: Graph to show results of Freedman and Fraser (1966)“The Assumptive Close” This technique refers to any action which assumes the customer has already decided to buy the product. A good example of this might be saying “We can deliver the goods to you by Friday at the earliest, would you prefer it in the morning or afternoon?”. As people, we don’t particularly like to correct others. Asking something like this makes it very difficult for the customer to then respond with something like “actually I don’t want it at all”. Asking questions like this can act as a form of presumed commitment. It works much in the same way as the foot-in-the-door technique. In this context, the response to the question acts as the smaller commitment leader to the bigger commitment (purchasing the item). Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) showed that individuals are more likely to make internal attributions when they experience cognitive dissonance in regard to the task. Individuals participated in a long and boring task and then had to tell another participant waiting to do the task that they had found it enjoyable. Participants were either paid £1 or £20. Individuals rated it as more enjoyable if they were paid less money. It is proposed that individuals who were paid £1 attribute the act of telling other people they enjoyed the task as internal because they can’t use the payment as justification and so they experience cognitive dissonance and change their attitude towards the task. In comparison, those who were paid £20 experience no dissonance and so their attitude towards the task remains stable – they found it boring.

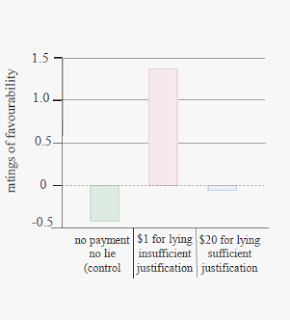

Figure one: Graph to show results of Freedman and Fraser (1966)“The Assumptive Close” This technique refers to any action which assumes the customer has already decided to buy the product. A good example of this might be saying “We can deliver the goods to you by Friday at the earliest, would you prefer it in the morning or afternoon?”. As people, we don’t particularly like to correct others. Asking something like this makes it very difficult for the customer to then respond with something like “actually I don’t want it at all”. Asking questions like this can act as a form of presumed commitment. It works much in the same way as the foot-in-the-door technique. In this context, the response to the question acts as the smaller commitment leader to the bigger commitment (purchasing the item). Festinger and Carlsmith (1959) showed that individuals are more likely to make internal attributions when they experience cognitive dissonance in regard to the task. Individuals participated in a long and boring task and then had to tell another participant waiting to do the task that they had found it enjoyable. Participants were either paid £1 or £20. Individuals rated it as more enjoyable if they were paid less money. It is proposed that individuals who were paid £1 attribute the act of telling other people they enjoyed the task as internal because they can’t use the payment as justification and so they experience cognitive dissonance and change their attitude towards the task. In comparison, those who were paid £20 experience no dissonance and so their attitude towards the task remains stable – they found it boring. Figure two: Graph to show results of Festinger and Carlsmith (1959)This may be applicable to assumptive closes in that you as the customer, may justify your answering of the small commitment questions by attributing it internally – “I actually want the product”. This would therefore lead to increased likelihood of purchasing. Perhaps I’m particularly naïve, but I’d never quite realised how carefully structured my conversations in a salesperson/customer interaction had been before, but then again, maybe that explains my impulsive spending. I like to think that with the knowledge I now have, I’ll be much more equipped to challenge my urges to buy and maybe even save some money. I hope this helps you all as much as it will (hopefully) help me.Vicky HillReferencesAzjen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control (pp.11-39). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203.Freedman, J.L., & Fraser, S.C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 195-202.

Figure two: Graph to show results of Festinger and Carlsmith (1959)This may be applicable to assumptive closes in that you as the customer, may justify your answering of the small commitment questions by attributing it internally – “I actually want the product”. This would therefore lead to increased likelihood of purchasing. Perhaps I’m particularly naïve, but I’d never quite realised how carefully structured my conversations in a salesperson/customer interaction had been before, but then again, maybe that explains my impulsive spending. I like to think that with the knowledge I now have, I’ll be much more equipped to challenge my urges to buy and maybe even save some money. I hope this helps you all as much as it will (hopefully) help me.Vicky HillReferencesAzjen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In Action Control (pp.11-39). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. Festinger, L., & Carlsmith, J. M. (1959). Cognitive consequences of forced compliance. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 58, 203.Freedman, J.L., & Fraser, S.C. (1966). Compliance without pressure: The foot-in-the-door technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4, 195-202.