Selfies themselves have exploded in popularity alongside the ever-expanding world of social media. Ellen DeGeneres’ Oscars selfie in 2014 became the most retweeted post in history at 2,070,132 retweets by the end of the Oscars ceremony (Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them, 2014). Tom Hanks congratulated a newly-wed couple by sharing a selfie on Instagram, whilst the UK’s Prime Minister posed for selfies on the red carpet on Monday evening (Theresa Manyia, 2016), all captured in figure one. Figures from 2014 state over 1,000,000 #selfies are taken each day, with 50% of men and 52% of woman having taken a selfie (The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures, 2014). Perhaps it is no surprise then that the selfie phenomena provided an opportunity for the charity Cancer Research UK to raise over £8,000,000 (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). Figure One. Left to right: Ellen’s Oscar selfie, Tom Hanks wedding congratulations selfie, Theresa May posing for red carpet selfies with the public The #nomakeupselfie was initiated by Laura Lipmann, for a different reason and with a different hashtag, but before long the internet had worked its magic and the no make-up selfie was generating tens of thousands of tweets a day. Cancer Research UK noticed the hashtag gaining momentum and attached a donation text number to the posts, raising £2,000,000 in the first 48 hours (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). It is safe to say the no make-up selfies are a perfect example of ‘going viral’. How was it then that a simple selfie influenced so many people to donate? How was a viral phenomenon influencing people’s behaviour a) getting them to upload a post they would not usually post, and b) getting them to donate money they would not have considered doing before-hand? Below are various influence techniques that appear to have been at play throughout the #nomakeupselfie phenomena. Availability Heuristic and Social NormsThe availability heuristic suggests the easier something comes to mind, the higher we estimate the frequency of an event (Schwarz et al, 1991). Agenda setting theory extends this and suggests the media can manipulate what we think about by the frequency of which it shares a story (Walgrave & Aelst, 2006). With tens of thousands of woman engaging, it is not surprising the posts filled our timelines and reached mainstream media (Deller & Tilton, 2015). The no-make up selfie was then at the forefront of our minds, and we very quickly believed that everyone was doing it.Sherif and Sherif (1953) first defined social norms as our standards formed through our group interactions, that we will follow as individuals. Through the surge of no make-up selfie posts, the media ensured we perceived the no-make selfies as the latest norm. In the interest of fitting in and wanting to part of the in-group of our online friendship networks, we soon are likely to have taken the selfie ourselves and are contributing to the mass selfie uploads and adding to the growing donations. Celebrity Endorsement

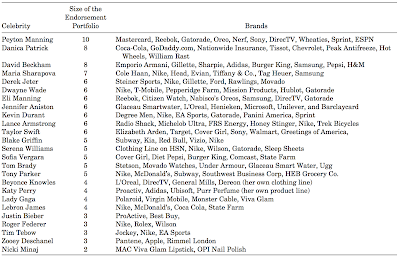

Figure One. Left to right: Ellen’s Oscar selfie, Tom Hanks wedding congratulations selfie, Theresa May posing for red carpet selfies with the public The #nomakeupselfie was initiated by Laura Lipmann, for a different reason and with a different hashtag, but before long the internet had worked its magic and the no make-up selfie was generating tens of thousands of tweets a day. Cancer Research UK noticed the hashtag gaining momentum and attached a donation text number to the posts, raising £2,000,000 in the first 48 hours (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). It is safe to say the no make-up selfies are a perfect example of ‘going viral’. How was it then that a simple selfie influenced so many people to donate? How was a viral phenomenon influencing people’s behaviour a) getting them to upload a post they would not usually post, and b) getting them to donate money they would not have considered doing before-hand? Below are various influence techniques that appear to have been at play throughout the #nomakeupselfie phenomena. Availability Heuristic and Social NormsThe availability heuristic suggests the easier something comes to mind, the higher we estimate the frequency of an event (Schwarz et al, 1991). Agenda setting theory extends this and suggests the media can manipulate what we think about by the frequency of which it shares a story (Walgrave & Aelst, 2006). With tens of thousands of woman engaging, it is not surprising the posts filled our timelines and reached mainstream media (Deller & Tilton, 2015). The no-make up selfie was then at the forefront of our minds, and we very quickly believed that everyone was doing it.Sherif and Sherif (1953) first defined social norms as our standards formed through our group interactions, that we will follow as individuals. Through the surge of no make-up selfie posts, the media ensured we perceived the no-make selfies as the latest norm. In the interest of fitting in and wanting to part of the in-group of our online friendship networks, we soon are likely to have taken the selfie ourselves and are contributing to the mass selfie uploads and adding to the growing donations. Celebrity Endorsement Figure Two: Celebrity endorsement portfolios (Keating & Rice, 2013)Celebrity endorsement ties into the influence of both availability heuristic and social norms, with multiple brands using celebrities to advertise their goods, as outlined in figure two (Keating & Rice, 2013). Research by Keating and Rice (2013) measured recall of products when they were presented with a celebrity (celebrity cue) or with no cue. When looking at their results (displayed in figure three), it is understandable why such a vast majority of brands invest in celebrity marketing techniques, with moderate levels of celebrity cues significantly increasing recall of the products.

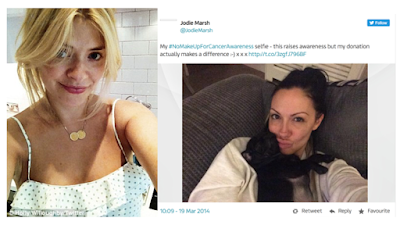

Figure Two: Celebrity endorsement portfolios (Keating & Rice, 2013)Celebrity endorsement ties into the influence of both availability heuristic and social norms, with multiple brands using celebrities to advertise their goods, as outlined in figure two (Keating & Rice, 2013). Research by Keating and Rice (2013) measured recall of products when they were presented with a celebrity (celebrity cue) or with no cue. When looking at their results (displayed in figure three), it is understandable why such a vast majority of brands invest in celebrity marketing techniques, with moderate levels of celebrity cues significantly increasing recall of the products.  Figure Three: Percentage of consumers who recalled the product with and without celebrity cues (Keating & Rice, 2013)If we extend this outside of purchasing environments, individuals are likely to have higher chances of recalling a given ‘thing’ if a celebrity has been associated with it. Once again, the availability heuristic is at play; if the celebrities are taking part (as demonstrated by Holly Willoughby and Jodie Marsh in figure three), everyone must be doing it. Thus, we are more likely to upload a no make-up selfie ourselves and make a donation in order to fit in with the ever-growing social norms.

Figure Three: Percentage of consumers who recalled the product with and without celebrity cues (Keating & Rice, 2013)If we extend this outside of purchasing environments, individuals are likely to have higher chances of recalling a given ‘thing’ if a celebrity has been associated with it. Once again, the availability heuristic is at play; if the celebrities are taking part (as demonstrated by Holly Willoughby and Jodie Marsh in figure three), everyone must be doing it. Thus, we are more likely to upload a no make-up selfie ourselves and make a donation in order to fit in with the ever-growing social norms. Figure Three. Left to right: Holly Willoughby’s and Jodie Marsh’s #nomakeupselfieRole ModelsIn addition, celebrities are traditionally seen as attractive and likeable individuals who are considered to be highly influential (Kamins et al, 1989), and therefore can be important influencers of behaviour (Bush, Martin & Bush, 2004). If individuals are aspiring to be like a celebrity role model, they could be more likely to model their behaviours (Singh, Vinnicombe & James, 2006) and in this case, also upload a no make-up selfie and make the donation to Cancer Research UK.Just AskOne of the key ‘weapons’ Cialdini (2000) identifies for influencing behaviour is simply asking for what you want. Research has shown, for example that 56% of females asked by a male stranger would agree to go on a date with him (Clark & Hatfield, 1989). As the #nomakeupselfie posts continued to grow, girls began to nominate three friends within their posts who should do the selfie next (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Like asking strangers on dates, people are more likely to conform to a behaviour when they are asked to do so directly, which could again, be increasing the likelihood of individuals posting no make-up selfies and donating. AttitudesThe British culture is one very heavily influenced by what others think of us. It is no secret we want to be viewed positively by our peers; a view that can be created through giving generously and selflessly (Li, Pickles & Savage, 2005). Compassion and generosity have been rated as two of the most important factors when rating how much we like other peers (Hartley et al, 2016). With these pre-conceived attitudes within the British culture, it is easy to see how so many were influenced to donate to Cancer Research UK; fast to be perceived as generous, selfless and therefore likeable to others. The no-make up selfies were considered both selfless through the donations and brave in uploading a photo in which they were not comfortable uploading, and as stated by Deller and Tilton (2015), selflessness and bravery is rewarded. ConsistencyCialdini (2000) also identifies consistency as one of the weapons in influencing behaviour. This is a phenomenon that states once we have made a stand, particularly in public, we are more likely to act consistent with this behaviour. For example, students were significantly more likely to stick to the estimates they had given for the length of a line when they declared the length publicly, as opposed to privately (Deutch & Gerard, 1955). Once individuals have taken their no-make up selfie and shared it on social media, they have made a public stand for their support for Cancer Research UK, and are therefore more likely to donate to the charity alongside their selfie, hence the £8,000,000 raised alongside the tens of thousands of selfies uploaded (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014).Above are just a select few of the techniques that may have encouraged people to participate in the #nomakeupselfie’s themselves, with others ranging from peer pressure to becoming a ‘killjoy’ for not taking part (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Whatever it was that made people get involved has got charities and marketers hunting it down in in order to become the next fund-raising phenomenon. If we are to take anything away from these viral selfies, realise and remember that behavioural influences can be used for the greater good. Thanks to the posts and donations of bare-faced woman, 10 new clinical trials could be funded, amongst other streams of research (#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered, 2014). A step closer to a cure for cancer has got to be making the world a better place. References#nomakeupselfie – why it worked. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2014/mar/25/nomakeupselfie-viral-campaign-cancer-research#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2014/03/25/nomakeupselfie-some-questions-answered/Bush, A. J., Martin, C. A., & Bush, V. D. (2004). Sports celebrity influence on the behavioral intentions of generation Y. Journal of Advertising Research, 44(01), 108-118.Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Collins.Clark, R. D. & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of psychology and human sexuality, 2, 39-55.Deller, R. A. & Tilton, S. (2015). Selfies as charitable meme: charity and national identity in the #nomakeupselfie and the #thumbsupforstephen campaigns. International journal of communication, 9, 1788-1805. Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The journal of abnormal and social psychology, 51(3), 629.Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them. (2014, March 7). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/mar/07/oscars-selfie-most-retweeted-everHartley, A. G., Furr, R. M., Helzer, E. G., Jayawickreme, E., Velasquez, K. R., & Fleeson, W. (2016). Morality’s centrality to liking, respecting, and understanding others. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1948550616655359.Kelting, K., & Rice, D. H. (2013). Should we hire David Beckham to endorse our brand? Contextual interference and consumer memory for brands in a celebrity’s endorsement portfolio. Psychology & Marketing, 30(7), 602-613.Li, Y., Pickles, A., & Savage, M. (2005). Social capital and social trust in Britain. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 109-123.Michael, A. K., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: the impact on advertising effectiveness and credibility. Journal of advertising, 18, 4-10.Radha, G. & Jija, P. (2013). Influence of celebrity endorsement on the consumer’s purchase decision. International journal of scientific and research publications, 3, 1-28.Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 61(2), 195.Sherif, M. & Sherif, C. W. (1953). Groups in harmony and tension. New York: Harper. Singh, V., Vinnicombe, S., & James, K. (2006). Constructing a professional identity: how young female managers use role models. Women in Management Review, 21(1), 67-81.The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures. (2014, March 19). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/selfie-statistics-2014/497309Theresa Maynia! (2016, October 31). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3891738/Theresa-Maynia-Selfies-autographs-red-carpet-PM-works-crowd-like-true-lister-Pride-Britain-awards.htmlWalgrave, S., & Van Aelst, P. (2006). The contingency of the mass media’s political agenda setting power: toward a preliminary theory. Journal of communication, 56, 88-109.

Figure Three. Left to right: Holly Willoughby’s and Jodie Marsh’s #nomakeupselfieRole ModelsIn addition, celebrities are traditionally seen as attractive and likeable individuals who are considered to be highly influential (Kamins et al, 1989), and therefore can be important influencers of behaviour (Bush, Martin & Bush, 2004). If individuals are aspiring to be like a celebrity role model, they could be more likely to model their behaviours (Singh, Vinnicombe & James, 2006) and in this case, also upload a no make-up selfie and make the donation to Cancer Research UK.Just AskOne of the key ‘weapons’ Cialdini (2000) identifies for influencing behaviour is simply asking for what you want. Research has shown, for example that 56% of females asked by a male stranger would agree to go on a date with him (Clark & Hatfield, 1989). As the #nomakeupselfie posts continued to grow, girls began to nominate three friends within their posts who should do the selfie next (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Like asking strangers on dates, people are more likely to conform to a behaviour when they are asked to do so directly, which could again, be increasing the likelihood of individuals posting no make-up selfies and donating. AttitudesThe British culture is one very heavily influenced by what others think of us. It is no secret we want to be viewed positively by our peers; a view that can be created through giving generously and selflessly (Li, Pickles & Savage, 2005). Compassion and generosity have been rated as two of the most important factors when rating how much we like other peers (Hartley et al, 2016). With these pre-conceived attitudes within the British culture, it is easy to see how so many were influenced to donate to Cancer Research UK; fast to be perceived as generous, selfless and therefore likeable to others. The no-make up selfies were considered both selfless through the donations and brave in uploading a photo in which they were not comfortable uploading, and as stated by Deller and Tilton (2015), selflessness and bravery is rewarded. ConsistencyCialdini (2000) also identifies consistency as one of the weapons in influencing behaviour. This is a phenomenon that states once we have made a stand, particularly in public, we are more likely to act consistent with this behaviour. For example, students were significantly more likely to stick to the estimates they had given for the length of a line when they declared the length publicly, as opposed to privately (Deutch & Gerard, 1955). Once individuals have taken their no-make up selfie and shared it on social media, they have made a public stand for their support for Cancer Research UK, and are therefore more likely to donate to the charity alongside their selfie, hence the £8,000,000 raised alongside the tens of thousands of selfies uploaded (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014).Above are just a select few of the techniques that may have encouraged people to participate in the #nomakeupselfie’s themselves, with others ranging from peer pressure to becoming a ‘killjoy’ for not taking part (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Whatever it was that made people get involved has got charities and marketers hunting it down in in order to become the next fund-raising phenomenon. If we are to take anything away from these viral selfies, realise and remember that behavioural influences can be used for the greater good. Thanks to the posts and donations of bare-faced woman, 10 new clinical trials could be funded, amongst other streams of research (#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered, 2014). A step closer to a cure for cancer has got to be making the world a better place. References#nomakeupselfie – why it worked. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2014/mar/25/nomakeupselfie-viral-campaign-cancer-research#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2014/03/25/nomakeupselfie-some-questions-answered/Bush, A. J., Martin, C. A., & Bush, V. D. (2004). Sports celebrity influence on the behavioral intentions of generation Y. Journal of Advertising Research, 44(01), 108-118.Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Collins.Clark, R. D. & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of psychology and human sexuality, 2, 39-55.Deller, R. A. & Tilton, S. (2015). Selfies as charitable meme: charity and national identity in the #nomakeupselfie and the #thumbsupforstephen campaigns. International journal of communication, 9, 1788-1805. Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The journal of abnormal and social psychology, 51(3), 629.Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them. (2014, March 7). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/mar/07/oscars-selfie-most-retweeted-everHartley, A. G., Furr, R. M., Helzer, E. G., Jayawickreme, E., Velasquez, K. R., & Fleeson, W. (2016). Morality’s centrality to liking, respecting, and understanding others. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1948550616655359.Kelting, K., & Rice, D. H. (2013). Should we hire David Beckham to endorse our brand? Contextual interference and consumer memory for brands in a celebrity’s endorsement portfolio. Psychology & Marketing, 30(7), 602-613.Li, Y., Pickles, A., & Savage, M. (2005). Social capital and social trust in Britain. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 109-123.Michael, A. K., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: the impact on advertising effectiveness and credibility. Journal of advertising, 18, 4-10.Radha, G. & Jija, P. (2013). Influence of celebrity endorsement on the consumer’s purchase decision. International journal of scientific and research publications, 3, 1-28.Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 61(2), 195.Sherif, M. & Sherif, C. W. (1953). Groups in harmony and tension. New York: Harper. Singh, V., Vinnicombe, S., & James, K. (2006). Constructing a professional identity: how young female managers use role models. Women in Management Review, 21(1), 67-81.The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures. (2014, March 19). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/selfie-statistics-2014/497309Theresa Maynia! (2016, October 31). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3891738/Theresa-Maynia-Selfies-autographs-red-carpet-PM-works-crowd-like-true-lister-Pride-Britain-awards.htmlWalgrave, S., & Van Aelst, P. (2006). The contingency of the mass media’s political agenda setting power: toward a preliminary theory. Journal of communication, 56, 88-109.

So, you want to be like Kylie Jenner? The Psychology of Celebrity Endorsement.

It might not surprise you, but Kylie Jenner doesn’t ACTUALLY buy her lavish clothes from the high street store ‘Miss Pap’, and no, she’s not ‘in love’ with her new Daniel Wellington watch – she’s got her own 50K alternative, you do the maths. So why is she posting all these products on her social media pages? Throughout this blog, I shall delve into the concept of ‘celebrity endorsements’, how these celebs use their roles in the social world, image and popularity to create persuasion like no other.  As of 2015, there has been recorded to be around $2.3 billion active social users. Within this, these social networks have earned what is estimated to be around $8.3 billion from advertising alone. It might not then be too unexpected to hear that a huge 91% of retail brands actually use 2 or more social medial channels, spending up to 20% of their budgets on this social media advertisement, (“96 amazing social media statistics and facts for 2016,” 2016). In an analysis of consumer responses to identical brand publicity in seven popular blogs and seven popular online magazines, Colliander and Dahlen (2011), found that blogs generated higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions. In today’s new, social media frenzied world; we see celebrity product placement, whether it be on Instagram, Twitter or Snapchat most of our browsing days. One might ask, why do celebrities use these product placements? Product placement isn’t a new craze, it can be seen throughout even the 1790’s – starting with royal endorsements and the promotion of ‘Wedgwood’, a pottery and chinaware company, (I know, nothing like the constant bombardment of the oh so ‘popular’ Boo Tea shakes; which apparently every celeb is using these days as a result of needing to ‘get back at it after the weekend’ – their diet presumably, see Figure 1).

As of 2015, there has been recorded to be around $2.3 billion active social users. Within this, these social networks have earned what is estimated to be around $8.3 billion from advertising alone. It might not then be too unexpected to hear that a huge 91% of retail brands actually use 2 or more social medial channels, spending up to 20% of their budgets on this social media advertisement, (“96 amazing social media statistics and facts for 2016,” 2016). In an analysis of consumer responses to identical brand publicity in seven popular blogs and seven popular online magazines, Colliander and Dahlen (2011), found that blogs generated higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions. In today’s new, social media frenzied world; we see celebrity product placement, whether it be on Instagram, Twitter or Snapchat most of our browsing days. One might ask, why do celebrities use these product placements? Product placement isn’t a new craze, it can be seen throughout even the 1790’s – starting with royal endorsements and the promotion of ‘Wedgwood’, a pottery and chinaware company, (I know, nothing like the constant bombardment of the oh so ‘popular’ Boo Tea shakes; which apparently every celeb is using these days as a result of needing to ‘get back at it after the weekend’ – their diet presumably, see Figure 1).Figure 1. (Celebrity Endorsement – Throughout the Ages, 2004)I mean, chances of them actually using these products are very slim – they’re only in it for he paycheck, as so beautifully demonstrated by Scott Disick in this hilarious post, see Figure 2:

Figure 2. (O’Toole, 2016)In this quickly deleted, but forever unforgotten; Instagram post, Scott Disick reveals details on his social media product placement extents by LITERALLY COPYING AND PASTING instructions given to him by Boo Tea on how to promote their product, a big mistake to make when you are earning up to $20,000 for posting. So why do these celebrities endorse products in which they probably have no need, or want; to use in the first place? In the 2000’s, research has shown that by having celebrity ambassadors promote your products, sales dramatically improve. An example demonstrating this finding comes from Nike – by using Tiger Woods to promote their golf balls, a $50 million increase in golf ball sales occurred between 1996 and 2002, (Celebrity Endorsement – Throughout the Ages, 2004). How did this simple use of a celebrity provide such dramatic increase in sales? We can look at this through the psychological phenomena..Social Proof

The more it appears everyone is doing it, the more likely others will join and agree. We seem to determine what is correct by looking at what other people think is correct, (Lun et al,. 2007). In reference to product placement, the way in which celebrity endorsements promote sales could be explained by this phenomena. A simple study by Latane and Darley (1968), demonstrates this perfectly. You’re sat in a room and suddenly it begins to fill with smoke, you’re going to get out, right? I mean, that seems like the obvious answer to me, however; this study exhibited different findings. The researchers found that where there were 2 passive confederates whom acted as though nothing was wrong, whilst the room filled with smoke; only 10% of the subjects in their study actually left the room or reported the problem. The rest of them carried on with their task, simply waving the smoke from their faces. Back to product placement – when we are constantly seeing that people, who are deemed to be representative of what is desirable in society; are using these certain products – we are going to want to use them to. It is this provision of both normative and informational influence which promotes us to try out these ‘great’ products. Like the participants in the above study, we simply follow what it looks like most people are doing. We don’t have to think ourselves that a certain product is good, we only need to think that others think it is good. Associative Learning

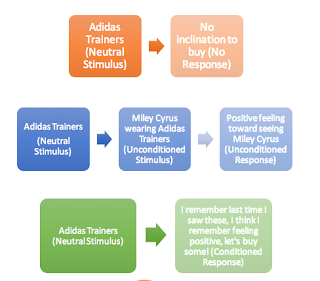

The more it appears everyone is doing it, the more likely others will join and agree. We seem to determine what is correct by looking at what other people think is correct, (Lun et al,. 2007). In reference to product placement, the way in which celebrity endorsements promote sales could be explained by this phenomena. A simple study by Latane and Darley (1968), demonstrates this perfectly. You’re sat in a room and suddenly it begins to fill with smoke, you’re going to get out, right? I mean, that seems like the obvious answer to me, however; this study exhibited different findings. The researchers found that where there were 2 passive confederates whom acted as though nothing was wrong, whilst the room filled with smoke; only 10% of the subjects in their study actually left the room or reported the problem. The rest of them carried on with their task, simply waving the smoke from their faces. Back to product placement – when we are constantly seeing that people, who are deemed to be representative of what is desirable in society; are using these certain products – we are going to want to use them to. It is this provision of both normative and informational influence which promotes us to try out these ‘great’ products. Like the participants in the above study, we simply follow what it looks like most people are doing. We don’t have to think ourselves that a certain product is good, we only need to think that others think it is good. Associative Learning  If you received an award in front of someone you previously were neutral towards, the probability of liking them increases. The positive aspects of the reward become associated with the person, (Lott & Lott, 1965).The effect of celebrity endorsements within the world of advertising can be explained through these associative learning principles. As demonstrated in Brian Till’s 1998 paper, when we see pictures of our favourite celebrities appearing on our newsfeed or in our search bars, we feel a certain amount of positive feeling – it is nice to see someone you like or perhaps look up to, right? By getting these celebrities with large fan bases to endorse products, we learn to associate these positive feelings we have about the celebrity alone with the product that they commonly endorse. Like the research findings from Lott and Lott (1965), the positive aspects of the celebrity become associated with the product. This leads us to think we have these positive feelings to, a certain trainer brand let’s say; and is going to make us much more likely to pick this brand over another when it comes to it. Look to the diagram above for a visual explanation!Source Credibility

If you received an award in front of someone you previously were neutral towards, the probability of liking them increases. The positive aspects of the reward become associated with the person, (Lott & Lott, 1965).The effect of celebrity endorsements within the world of advertising can be explained through these associative learning principles. As demonstrated in Brian Till’s 1998 paper, when we see pictures of our favourite celebrities appearing on our newsfeed or in our search bars, we feel a certain amount of positive feeling – it is nice to see someone you like or perhaps look up to, right? By getting these celebrities with large fan bases to endorse products, we learn to associate these positive feelings we have about the celebrity alone with the product that they commonly endorse. Like the research findings from Lott and Lott (1965), the positive aspects of the celebrity become associated with the product. This leads us to think we have these positive feelings to, a certain trainer brand let’s say; and is going to make us much more likely to pick this brand over another when it comes to it. Look to the diagram above for a visual explanation!Source Credibility Credibility is an important aspect to persuasion. If a message comes from a credible source, we are more likely to trust and act upon it. A study by Goldsmith, Lafferty, & Newell (2000), assessed the impact endorser credibility had on the shaping of attitudes towards brands. It was found that endorser credibility had the strongest impact on the participants’ attitudes towards the brand and purchase intentions, even more so than the corporates’ own credibility. If you are a huge fan of a certain celebrity, you probably perceive them as a trustworthy person. People who are trustworthy, physically attractive, have high social status and power must hold the correct attitudes. If they say that a product is good, it is good. People are more likely to attribute credibility to a company if they are using endorsement through a celebrity that you trust. Landscaping Techniques‘If you want to move a marble on a table, you can push it or you can lift the opposite end of the table. Pushing it is persuasion, lifting is pre-persuasion’ (Pratkanis, 2007) Celebrity endorsements can be considered as an example of pre-propaganda, through the creation of images and stereotypes – ‘It is cool to use this product because Justin Bieber does’; is a type of preconditioning of the public. Social Modelling

Credibility is an important aspect to persuasion. If a message comes from a credible source, we are more likely to trust and act upon it. A study by Goldsmith, Lafferty, & Newell (2000), assessed the impact endorser credibility had on the shaping of attitudes towards brands. It was found that endorser credibility had the strongest impact on the participants’ attitudes towards the brand and purchase intentions, even more so than the corporates’ own credibility. If you are a huge fan of a certain celebrity, you probably perceive them as a trustworthy person. People who are trustworthy, physically attractive, have high social status and power must hold the correct attitudes. If they say that a product is good, it is good. People are more likely to attribute credibility to a company if they are using endorsement through a celebrity that you trust. Landscaping Techniques‘If you want to move a marble on a table, you can push it or you can lift the opposite end of the table. Pushing it is persuasion, lifting is pre-persuasion’ (Pratkanis, 2007) Celebrity endorsements can be considered as an example of pre-propaganda, through the creation of images and stereotypes – ‘It is cool to use this product because Justin Bieber does’; is a type of preconditioning of the public. Social Modelling As most famously demonstrated in the ‘Bobo doll’ study, Bandura, Ross and Ross (1961), provided evidence for the case of learning via observation, imitation and modelling. People learn from one another. The celebrities you follow on your own social media feeds can be considered to be your important role models. It has been found that role models play a big part on teenager purchase intentions (Makgosa, 2010). By seeing your favourite role model endorse something, the likelihood of you to then consequently buy that product increases. We learn how to behave, in relation to our consumerism, by the way that our role models demonstrate we should. These celebrity endorsements are actually shaping our own purchase intentions. Agenda Setting and the Availability Heuristic

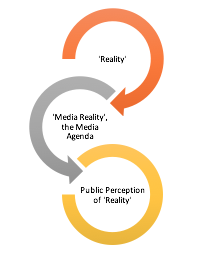

As most famously demonstrated in the ‘Bobo doll’ study, Bandura, Ross and Ross (1961), provided evidence for the case of learning via observation, imitation and modelling. People learn from one another. The celebrities you follow on your own social media feeds can be considered to be your important role models. It has been found that role models play a big part on teenager purchase intentions (Makgosa, 2010). By seeing your favourite role model endorse something, the likelihood of you to then consequently buy that product increases. We learn how to behave, in relation to our consumerism, by the way that our role models demonstrate we should. These celebrity endorsements are actually shaping our own purchase intentions. Agenda Setting and the Availability Heuristic This theory relates to the ability of the media to influence what topics are salient in the public agenda. Things which are placed highly on this agenda will appear to be more important and subsequently used to define the criteria used in the general public’s’ subsequent decisions. By setting agendas, the media (the products in which are regularly endorsed by celebrities, in this case) can limit the items that are thought about by the public exclusively to those that they want you thinking about. For example, repeated discussion of an issue in the media leads viewers to think it is more important, (Iyengar & Simon, 1983).Taking an instagram feed for example, if one were to follow a set of celebrities from the same sort of group, it would be likely to find that they were endorsing similar products. This provides these specific products to be top of my agenda. When it comes to purchases, I am much more likely to sway towards these. My ‘reality’ may be that I do not have any need for a Boo Tea prescription. However, when I see Louis Tomlinson, (along with many other celebs on my feed) tell me day to day that Boo Tea is an important aspect of his life, that becomes the ‘Media Reality’ – Boo Tea is needed. My new reality is a fabrication of what I have seen being promoted most regularly in the media, which leads me to want to purchase said product. This ties in with availability heuristics, a form of System 1 automatic and effortless thinking leading to preferential consumer patterns for those products most available to mind. Regularly endorsed products have seen, on average, a 2% increase in stock returns as compared to those less regularly endorsed by celebrities, (Elberse & Verleun 2012). Oh, so that’s why companies pay thousands to celebrities to post pictures of them with their products… Message Repetition and Mere ExposureWith a slightly similar basis to agenda setting and availability heuristics, message repetition can increase believability and acceptance. Mere, repeated exposure of an individual to a stimulus enhances his or her attitude towards it, the mere exposure provides a condition which makes the stimulus more accessible to perception, (Zajonk, 1968). The idea of mere exposure has been used to explain product placement (Vollmers & Mizerski, 1994). Mere exposure, in relation to product placement, can be explained like this – viewers will develop more favourable feelings towards a brand simply because of their repeated exposure to it – as demonstrated by Baker, (1999). This mere exposure doesn’t even need to be recalled, a simple repetition of exposure will lead to more favourable attitudes towards that brand (Janiszewski, 1993). It is common to see that celebrities have a select range of products in which they are regular endorsers for. This provides repetition of the message ‘buy this’ for each of those products to create stronger want to purchase said product. This explains the rise in sales for these regularly endorsed products. Theory of Planned Behaviour The theory of planned behaviour (Figure 3) comprises of three suggested components that lead to an intention to perform said behaviour.

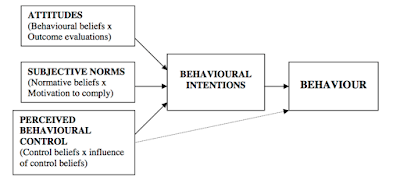

This theory relates to the ability of the media to influence what topics are salient in the public agenda. Things which are placed highly on this agenda will appear to be more important and subsequently used to define the criteria used in the general public’s’ subsequent decisions. By setting agendas, the media (the products in which are regularly endorsed by celebrities, in this case) can limit the items that are thought about by the public exclusively to those that they want you thinking about. For example, repeated discussion of an issue in the media leads viewers to think it is more important, (Iyengar & Simon, 1983).Taking an instagram feed for example, if one were to follow a set of celebrities from the same sort of group, it would be likely to find that they were endorsing similar products. This provides these specific products to be top of my agenda. When it comes to purchases, I am much more likely to sway towards these. My ‘reality’ may be that I do not have any need for a Boo Tea prescription. However, when I see Louis Tomlinson, (along with many other celebs on my feed) tell me day to day that Boo Tea is an important aspect of his life, that becomes the ‘Media Reality’ – Boo Tea is needed. My new reality is a fabrication of what I have seen being promoted most regularly in the media, which leads me to want to purchase said product. This ties in with availability heuristics, a form of System 1 automatic and effortless thinking leading to preferential consumer patterns for those products most available to mind. Regularly endorsed products have seen, on average, a 2% increase in stock returns as compared to those less regularly endorsed by celebrities, (Elberse & Verleun 2012). Oh, so that’s why companies pay thousands to celebrities to post pictures of them with their products… Message Repetition and Mere ExposureWith a slightly similar basis to agenda setting and availability heuristics, message repetition can increase believability and acceptance. Mere, repeated exposure of an individual to a stimulus enhances his or her attitude towards it, the mere exposure provides a condition which makes the stimulus more accessible to perception, (Zajonk, 1968). The idea of mere exposure has been used to explain product placement (Vollmers & Mizerski, 1994). Mere exposure, in relation to product placement, can be explained like this – viewers will develop more favourable feelings towards a brand simply because of their repeated exposure to it – as demonstrated by Baker, (1999). This mere exposure doesn’t even need to be recalled, a simple repetition of exposure will lead to more favourable attitudes towards that brand (Janiszewski, 1993). It is common to see that celebrities have a select range of products in which they are regular endorsers for. This provides repetition of the message ‘buy this’ for each of those products to create stronger want to purchase said product. This explains the rise in sales for these regularly endorsed products. Theory of Planned Behaviour The theory of planned behaviour (Figure 3) comprises of three suggested components that lead to an intention to perform said behaviour. Figure 3. The first component, perceived behavioural control; is the belief that you can in fact control your own behaviour – this could be related to the idea of an internal locus of control. Perhaps you never thought you could be similar to your favourite celebrity, but where you see constant posts surrounding the sorts of products celebrities buy – you can do the same and increase your similarities! Next, we have social norms. The fact that so many credible sources are advertising how good a product is, and that they actually use it themselves; increases the norms relating to that product. Something which may not have been considered as a purchase is suddenly becoming something that most people are using, so you should too. Attitudes towards the behaviour relate to what you actually think about something, in terms of products this could be, for example, your opinions on the use of home teeth whitening kits, which are highly endorsed by celebrities. We may have certain predispositions towards the health implications these teeth whitening kits may have, but perhaps due to this high exposure of people in the public eye using them and having no problems, these attitudes could become more positive. Theory of planned behaviour suggests that where you have a combination of these 3 components, there will be intent to perform the behaviour – in this case being buying the product that has been endorsed by the celebrity.So as we can see, perhaps it isn’t so crazy to be paying a celebrity $20,000 to post a picture of your products after all. Although it does cost, it does work – and pretty effectively too. Celebrity endorsements are extremely powerful in nature, and whilst they are used to increase sales of non harmful products, one must worry about the implications if they were to endorse anything else.. References Baker, W. E. (1999). When can affective conditioning and mere exposure directly influence brand choice? Journal of Advertising, 28, 31-46.Bandura, A., Ross, D. & Ross, S.A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63, 575-82.Celebrity Endorsement – Through the Ages. (2004). Retrieved October 27, 2016, from http://ibscdc.org/Free%20Cases/Celebrity%20Endorsement%20Through%20the%20Ages%20p1.htm Colliander, J., & Dahlen, M. (2011). Following the fashionable friend: The power of social media – weighing the publicity effectiveness of Blogs versus online magazines. Journal of Advertising Research, 51, 313.Iberse, A., & Verleun, J. (2012). The economic value of celebrity endorsements. Journal of Advertising Research, 52, 149.Goldsmith, R. E., Lafferty, B. A., & Newell, S. J. (2000). The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity credibility on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. Journal of Advertising, 29, 43–54.Iyengar, S., & Simon, A. (1993). News coverage of the gulf crisis and public opinion: A study of agenda-setting, priming, and framing. Communication Research, 20, 365–383.Janiszewski, C. (1993). Preattentive mere exposure effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 376-392. Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group Inhibition of Bystander Intervention in Emergencies. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 10, 215–221.Lott, A. J., & Lott, B. E. (1965). Group cohesiveness as interpersonal attraction: A review of relationships with antecedent and consequent variables. Psychological Bulletin, 64, 259–309Lun, J., Sinclair, S., Whitchurch, E. R., & Glenn, C. (2007). (Why) do I think what you think? Epistemic social tuning and implicit prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 957–972.Makgosa, R. (2010). The influence of vicarious role models on purchase intentions of Botswana teenagers. Young Consumers, 11, 307–319.O’Toole, C. (2016, May 19). Scott Disick appears to copy and paste Instagram product placement. Daily Mail. Retrieved October 27, 2016, from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3599720/Scott-Disick-appears-copy-paste-Instagram-product-placement-instructions-social-media.html#ixzz4OH9J2tkHPratkanis, A. R. (2007). The science of social influence: Advances and future progress. New York: Psychology Press.Till, B. D. (1998). Using celebrity endorsers effectively: Lessons from associative learning. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 7, 400–409.Vollmers, S., & Mizerski, R. (1994) A review and investigation into the effectiveness of product placement in films. In K. W. King (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1994 conference of the American Academy of Advertising (pp. 97-102). Athens, GA: American Academy of Advertising. Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1-27.96 amazing social media statistics and facts for 2016. (2016, March 7). Retrieved October 27, 2016, from Marketing, https://www.brandwatch.com/2016/03/96-amazing-social-media-statistics-and-facts-for-2016/

Killer Clowns, Agenda Setting Theory and the Theory of Planned Behaviour

By now, we’ve all seen them in one way or another. Whether it be in person (Halloween is approaching…), on our social media newsfeeds or in the media. Newspaper headlines read ‘Killer clown craze: 12 of the creepiest UK sightings’ (The Telegraph, 17th Oct), ‘Killer clown with machete threatens two girls in Suffolk’ (The Telegraph, 16th Oct), ‘Childline flooded with calls about killer clown craze’ (Daily Mail, 13th Oct). With the number of these ‘killer clowns’ growing exponentially, you’ve got to ask the question of what took this from a Halloween outfit to a craze confining communities to their homes.It may not come as a surprise that research has shown the media is strikingly successful in telling its audience what to think about. The more the media reports something, the more available that information is to us and the more frequently we think about it. The agenda setting theory, first proposed in 1922, outlines this effect. It is not surprising then, that killer clowns have become the topic of conversation with them consecutively filling newspaper headlines and their masks filling every scroll down social media. Could it be that this high exposure is what has caused the ‘craze’? Could it be that the volume of others putting on a mask is what is encouraging so many more to do the same?

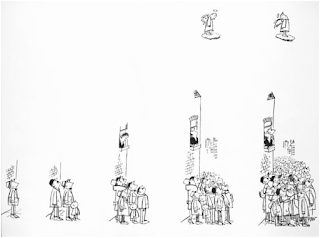

By now, we’ve all seen them in one way or another. Whether it be in person (Halloween is approaching…), on our social media newsfeeds or in the media. Newspaper headlines read ‘Killer clown craze: 12 of the creepiest UK sightings’ (The Telegraph, 17th Oct), ‘Killer clown with machete threatens two girls in Suffolk’ (The Telegraph, 16th Oct), ‘Childline flooded with calls about killer clown craze’ (Daily Mail, 13th Oct). With the number of these ‘killer clowns’ growing exponentially, you’ve got to ask the question of what took this from a Halloween outfit to a craze confining communities to their homes.It may not come as a surprise that research has shown the media is strikingly successful in telling its audience what to think about. The more the media reports something, the more available that information is to us and the more frequently we think about it. The agenda setting theory, first proposed in 1922, outlines this effect. It is not surprising then, that killer clowns have become the topic of conversation with them consecutively filling newspaper headlines and their masks filling every scroll down social media. Could it be that this high exposure is what has caused the ‘craze’? Could it be that the volume of others putting on a mask is what is encouraging so many more to do the same?  Figure One: The Theory of Planned BehaviourThe theory of planned behaviour suggests there are three components that lead to an intention to perform a certain behaviour (see figure one). Perceived behavioural control is simply the belief that you can control your behaviour. Perhaps the consequence of going out and scaring your community is too high; a risk of arrest, for example. But, thanks to the medias mass publications of clowns filling the streets, their perceived behavioural control is reassessed. An individual’s belief that they can to perform this behaviour grows, under the cover of a mask. Suddenly, a behaviour that seemed out of reach is not so anymore. This of course, ties in with social norms. Whilst it may have been considered unacceptable to go and scare your local community before, suddenly a lot more people doing it and it rapidly becomes a much more normative, and therefore an accepted behaviour to perform. Of course, it is the media that ensures we are aware of the growing number of clowns in our streets. The attitude towards the behaviour, in this example at least, is likely to build from the other components. The majority of us are probably horrified by these killer clowns, however, there are clearly individuals who have a more positive attitude to the craze. Or perhaps a more positive attitude of the behaviour has been formed as a result of the high exposure; it could be considered humourous rather than horrifying. According to the theory of planned behaviour, the combination of these three components lead to an intent to perform a behaviour. Although hard to get inside the head of a killer clown, you can see how putting on a mask, wig and wandering the local streets can suddenly be perceived as more acceptable; a belief that we possibly owe to media sources for sharing. This media exposure should boldly take its place in the diagram of the theory of planned behaviour, feeding into the three components that influence behaviour intentions (see figure two).

Figure One: The Theory of Planned BehaviourThe theory of planned behaviour suggests there are three components that lead to an intention to perform a certain behaviour (see figure one). Perceived behavioural control is simply the belief that you can control your behaviour. Perhaps the consequence of going out and scaring your community is too high; a risk of arrest, for example. But, thanks to the medias mass publications of clowns filling the streets, their perceived behavioural control is reassessed. An individual’s belief that they can to perform this behaviour grows, under the cover of a mask. Suddenly, a behaviour that seemed out of reach is not so anymore. This of course, ties in with social norms. Whilst it may have been considered unacceptable to go and scare your local community before, suddenly a lot more people doing it and it rapidly becomes a much more normative, and therefore an accepted behaviour to perform. Of course, it is the media that ensures we are aware of the growing number of clowns in our streets. The attitude towards the behaviour, in this example at least, is likely to build from the other components. The majority of us are probably horrified by these killer clowns, however, there are clearly individuals who have a more positive attitude to the craze. Or perhaps a more positive attitude of the behaviour has been formed as a result of the high exposure; it could be considered humourous rather than horrifying. According to the theory of planned behaviour, the combination of these three components lead to an intent to perform a behaviour. Although hard to get inside the head of a killer clown, you can see how putting on a mask, wig and wandering the local streets can suddenly be perceived as more acceptable; a belief that we possibly owe to media sources for sharing. This media exposure should boldly take its place in the diagram of the theory of planned behaviour, feeding into the three components that influence behaviour intentions (see figure two).  Figure Two: Addition of Agenda Setting to Theory of Planned BehaviourThe role of the media treads a very fine line. The damaging effects of them sharing the latest craze can clearly be seen, essentially taking what could have been a few separate instances to the ‘killer clown craze’. But, how long would it take for us to begin to resent the media should they stop sharing the latest horrors? Would we not be outraged if we came face-to-face with a killer clown only to find we could have been warned to stay in our homes, if the media had published the latest instances it had been informed of? Regardless, this latest craze illustrates the strength of agenda setting theory, and the power the media has over us and our behaviours.ReferencesFrancis, J. J., Eccles, M. P., Johnston, M., Walker, A., Grimshaw, J., Foy, R., Kaner, E. F. S., Smith, L., & Bonetti, D. (2004). Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour. A manual for health services researchers, 2010, 2-12. Rogers, E. M., Dearing, J. W., & Bregman, D. (1993). The anatomy of agenda‐setting research. Journal of communication, 43(2), 68-84.

Figure Two: Addition of Agenda Setting to Theory of Planned BehaviourThe role of the media treads a very fine line. The damaging effects of them sharing the latest craze can clearly be seen, essentially taking what could have been a few separate instances to the ‘killer clown craze’. But, how long would it take for us to begin to resent the media should they stop sharing the latest horrors? Would we not be outraged if we came face-to-face with a killer clown only to find we could have been warned to stay in our homes, if the media had published the latest instances it had been informed of? Regardless, this latest craze illustrates the strength of agenda setting theory, and the power the media has over us and our behaviours.ReferencesFrancis, J. J., Eccles, M. P., Johnston, M., Walker, A., Grimshaw, J., Foy, R., Kaner, E. F. S., Smith, L., & Bonetti, D. (2004). Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour. A manual for health services researchers, 2010, 2-12. Rogers, E. M., Dearing, J. W., & Bregman, D. (1993). The anatomy of agenda‐setting research. Journal of communication, 43(2), 68-84.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- …

- 88

- Next Page »