When I work with students in the Principles of Persuasion workshop we talk about three kinds of persuasion practitioners: bunglers, smugglers and detectives. Here’s a quick synopsis of each:Detectives are folks who understand the principles of influence and look for genuine opportunities to use them in order to create a win for themselves as well as the person or people they seek to influence.Smugglers are individuals who also have some understanding but they look for shortcuts through manipulation. They find it easier to distort the truth or lie outright in their use of the principles of influence so they can get what they want no matter the cost to others. Bunglers are people who don’t understand the persuasion process or principles and therefore miss opportunities to be more effective when it come to persuasion. Or, they might intuitively know a few things about the principles but don’t understand how to effectively use them. Unfortunately the vast majority of people fall into this category and they make predictable mistakes.In this post we’ll look at some of the most common mistakes people make when trying to persuade others. No offense, but if you find yourself doing these things, you’re bungling away persuasion opportunities.Validating undesirable behavior. There’s a lot of bad stuff that happens in society. For example; too many kids try cigarettes and cheat in school; far too many people don’t vote; violent behavior seems to be on the rise, etc. When you talk about what many people are doing – consensus – you tend to validate the bad behavior. This can cause more people to do the very thing you’re preaching against! Instead, you want to point out good behavior you want people to emulate. This approach was validated in the last two presidential elections where people were told to get to the polls early because record turnouts were expected. Those turnouts materialized. Highlighting gain instead of loss. I’ve shared in recent posts about homeowners who, when told about energy saving recommendations, were informed they would either save $180 by implementing the energy saving ideas or that they would lose $180 if they failed to implement the ideas, the latter of which is an application of the principle of scarcity. Everyone I share that study with correctly guesses more people in the “lose” group made the necessary changes. And they’re correct — 150% more people in the lose group chose to incorporate the energy saving ideas. Despite intuitively knowing this, most people still go out and talk about all the things someone will gain, or save, by going with their idea. Perhaps they fear coming across as negative but they’re failing to apply the most persuasive approach and they won’t hear yes as often.Confusing contracts with reciprocity. Reciprocity explains the reality that people feel obligated to return a favor. In other words, if I do something for you you’ll feel some obligation to want to do something for me in return. An example would be; I’ll do A and I hope you’ll do B in return. This is very different than entering into a contract – I’ll do A IF you’ll do B. Quite often you can engage reciprocity by doing or offering far less and still get the same behavior in return. Mixing up positional authority with perceived authority. Believing you’re an authorityis far different than other people perceiving you to be an authority. Sometimes others need to know your credentials. When people rely solely on their position to gain compliance it will never be as effective as it could be if they engaged people in the persuasion process by highlighting their credentials. It’s one thing for me to do something because the boss says so versus doing the very same thing because I see the value in doing so because an expert convinced me.Failing to connect on liking. Effective persuasion has a lot to do with relationships built on the principle of liking. It’s not always enough that someone likes your product or service. Quite often the difference maker is whether or not they like you. It doesn’t matter if you’re a salesperson, manager or someone else, spending too much time describing ideas, products, services, etc., without getting the other person to like you is going to make persuasion harder. And here’s the gem – make sure you create time to learn a bit about the other person so you come to like them and you’ll be amazed at the difference it can make!Telling instead of asking. Telling someone what to do isn’t nearly as effective as asking because asking engages consistency. This principle tells us people feel internal psychological pressure as well as external social pressure to be consistent in what they say and do. By asking and getting a “Yes” the odds that someone will do what you want increase significantly. In the POP workshop we talk about a restaurant owner who saw no shows fall from 30% to just 10% by having the hostess go from saying, “Please call of you cannot make your reservation” to asking, “Will you please call if you cannot keep your reservation?” The first sentence is a statement but the second is a question that engages consistency. Failure to give a reason. When you want someone to do something, giving a reason tagged with “because” can make all the difference. As I’ve share with State Auto claim reps, “Can you get me your medical records?” will not be as effective as “Can you get me your medical records because without them I cannot process your claim and pay you?” This approach was validated in a copier study where 50% more people (93% up from 60%) were willing to let someone go ahead of them in line when the person asking gave them a reason using the word “because.”So there you have some of the most common persuasion mistakes. By pointing them out hopefully you’ll change your ways if you’ve made these mistakes before. If you’ve not bungled like this then hopefully you’ll avoid these mistakes now that you’re aware of them.

When I work with students in the Principles of Persuasion workshop we talk about three kinds of persuasion practitioners: bunglers, smugglers and detectives. Here’s a quick synopsis of each:Detectives are folks who understand the principles of influence and look for genuine opportunities to use them in order to create a win for themselves as well as the person or people they seek to influence.Smugglers are individuals who also have some understanding but they look for shortcuts through manipulation. They find it easier to distort the truth or lie outright in their use of the principles of influence so they can get what they want no matter the cost to others. Bunglers are people who don’t understand the persuasion process or principles and therefore miss opportunities to be more effective when it come to persuasion. Or, they might intuitively know a few things about the principles but don’t understand how to effectively use them. Unfortunately the vast majority of people fall into this category and they make predictable mistakes.In this post we’ll look at some of the most common mistakes people make when trying to persuade others. No offense, but if you find yourself doing these things, you’re bungling away persuasion opportunities.Validating undesirable behavior. There’s a lot of bad stuff that happens in society. For example; too many kids try cigarettes and cheat in school; far too many people don’t vote; violent behavior seems to be on the rise, etc. When you talk about what many people are doing – consensus – you tend to validate the bad behavior. This can cause more people to do the very thing you’re preaching against! Instead, you want to point out good behavior you want people to emulate. This approach was validated in the last two presidential elections where people were told to get to the polls early because record turnouts were expected. Those turnouts materialized. Highlighting gain instead of loss. I’ve shared in recent posts about homeowners who, when told about energy saving recommendations, were informed they would either save $180 by implementing the energy saving ideas or that they would lose $180 if they failed to implement the ideas, the latter of which is an application of the principle of scarcity. Everyone I share that study with correctly guesses more people in the “lose” group made the necessary changes. And they’re correct — 150% more people in the lose group chose to incorporate the energy saving ideas. Despite intuitively knowing this, most people still go out and talk about all the things someone will gain, or save, by going with their idea. Perhaps they fear coming across as negative but they’re failing to apply the most persuasive approach and they won’t hear yes as often.Confusing contracts with reciprocity. Reciprocity explains the reality that people feel obligated to return a favor. In other words, if I do something for you you’ll feel some obligation to want to do something for me in return. An example would be; I’ll do A and I hope you’ll do B in return. This is very different than entering into a contract – I’ll do A IF you’ll do B. Quite often you can engage reciprocity by doing or offering far less and still get the same behavior in return. Mixing up positional authority with perceived authority. Believing you’re an authorityis far different than other people perceiving you to be an authority. Sometimes others need to know your credentials. When people rely solely on their position to gain compliance it will never be as effective as it could be if they engaged people in the persuasion process by highlighting their credentials. It’s one thing for me to do something because the boss says so versus doing the very same thing because I see the value in doing so because an expert convinced me.Failing to connect on liking. Effective persuasion has a lot to do with relationships built on the principle of liking. It’s not always enough that someone likes your product or service. Quite often the difference maker is whether or not they like you. It doesn’t matter if you’re a salesperson, manager or someone else, spending too much time describing ideas, products, services, etc., without getting the other person to like you is going to make persuasion harder. And here’s the gem – make sure you create time to learn a bit about the other person so you come to like them and you’ll be amazed at the difference it can make!Telling instead of asking. Telling someone what to do isn’t nearly as effective as asking because asking engages consistency. This principle tells us people feel internal psychological pressure as well as external social pressure to be consistent in what they say and do. By asking and getting a “Yes” the odds that someone will do what you want increase significantly. In the POP workshop we talk about a restaurant owner who saw no shows fall from 30% to just 10% by having the hostess go from saying, “Please call of you cannot make your reservation” to asking, “Will you please call if you cannot keep your reservation?” The first sentence is a statement but the second is a question that engages consistency. Failure to give a reason. When you want someone to do something, giving a reason tagged with “because” can make all the difference. As I’ve share with State Auto claim reps, “Can you get me your medical records?” will not be as effective as “Can you get me your medical records because without them I cannot process your claim and pay you?” This approach was validated in a copier study where 50% more people (93% up from 60%) were willing to let someone go ahead of them in line when the person asking gave them a reason using the word “because.”So there you have some of the most common persuasion mistakes. By pointing them out hopefully you’ll change your ways if you’ve made these mistakes before. If you’ve not bungled like this then hopefully you’ll avoid these mistakes now that you’re aware of them. Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”.

Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”.

Angry Facial Expressions in Negotiation

Wouldn’t you want to know the negotiation secret to closing the deal or securing that lucrative contract? Now new research out of Harvard University suggests your best weapon may be your facial expressions.

Wouldn’t you want to know the negotiation secret to closing the deal or securing that lucrative contract? Now new research out of Harvard University suggests your best weapon may be your facial expressions.

In a new paper entitled “The Commitment Function of Angry Facial Expressions” published in Psychological Science, Harvard University psychology post-doc Lawrence Ian Reed suggests that angry facial expressions seem to boost the effectiveness of threats without actual aggression.

Reed and colleagues Peter DeScioli of Stony Brook University and Steven Pinker of Harvard University conducted an online study of over 870 participants who were told they were playing a negotiation game.

As described in an article on Science Daily, during the study, participants acting as the “proposer,” would decide how to split a sum of $1.00 with another participant, the “responder.” Each person would receive the specified sum if the responder accepted the split that was offered, but neither person would receive any money if the responder rejected the split.

Before making their offers, each proposer was shown a threat that supposedly came from the responder. In reality, the responder was played by the same female actor, who was instructed to create specific facial expressions in the video clips. One clip showed her making a neutral expression, while another showed her making an angry expression.

The clips were accompanied by a written demand for either an equal cut of 50% or a larger cut of 70%, (which would leave only 30% for the proposer).

After they saw the threat, the proposers were asked to state their offer.

The data revealed that the responder’s facial expression did have an impact on the amount offered by the proposer, but only when the responder demanded the larger share.

That is, proposers offered more money if the responder showed an angry expression compared to when they showed a neutral expression, but only when the responder demanded 70% of the take.

Facial expression had no influence on proposers’ offers when the responder demanded an equal share, presumably because the demand was already viewed as credible.

Interestingly, proposers offered greater amounts in response to angry facial expressions compared to neutral expressions even when they were told that they belonged to a “typical responder,” rather than their specific partner.

The researchers claim this works because genuine facial expressions of emotions are hard to fake. Since it’s difficult to fake your emotional expression, people unconsciously assign that more importance than what you’re actually saying. “We pay attention to what people ‘say’ with their faces more than what they say with words,” Reed says.

“The effectiveness of the threat depends on how credible it is,” he says. An angry expression makes a threat more credible because people intuitively think it’s genuine. Whoever you’re negotiating with is more likely to think you’ll follow through on taking your business elsewhere or walking away on a job offer if your words are delivered with the look you’d give a person with a cart full of groceries in the express checkout lane.

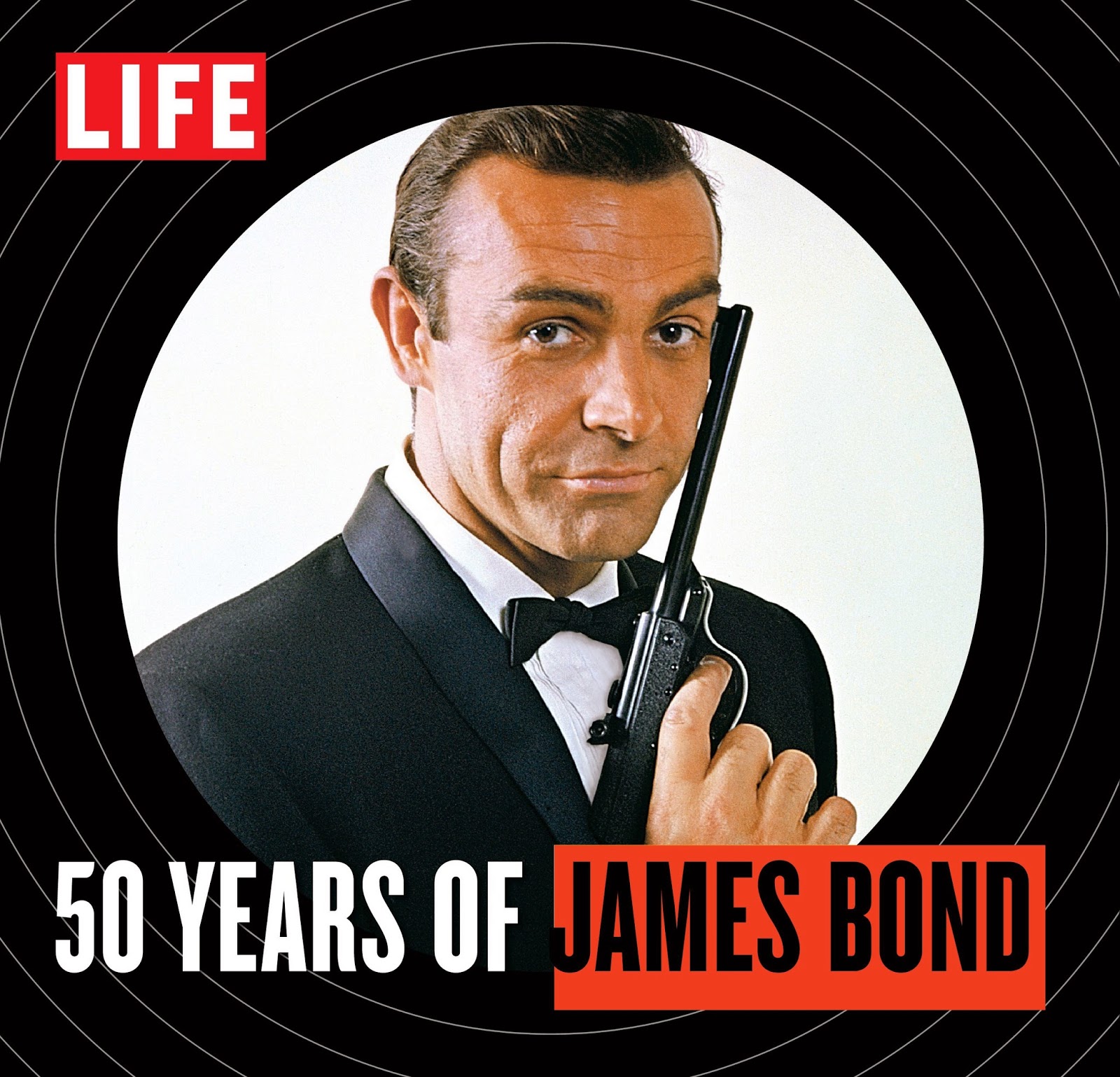

James Bond needs no introduction, but you do!

I read an article not too long ago that a friend passed along and felt compelled to share my thoughts about it. The article appeared in Forbes.com and was titled “Why Public Speakers Need To Copy James Bond.” That’s a compelling title for Bond fans and speakers alike – of which I’m both – so I got sucked in and read. The author’s piece was well written and compelling…unless you know something about the psychology of persuasion. The gist of the article was this – Bond movies open with compelling action-packed scenes, not the credits, to immediately hook moviegoers. Speakers should do the same by starting immediately with a compelling story. I wholeheartedly agree that a speaker starting with a good story hooks the audience but foregoing a brief introduction misses out on a golden opportunity to utilize the principle of authority which will make you more persuasive, according to the science of influence. Imagine going to a conference and getting ready to listen to a speaker you’ve never heard of before. Will you pay more or less attention if you quickly learn beforehand the speaker was the top salesperson in their organization, or had a doctorate, or was one of only a handful in the world who does what he/she does, or had some other fact that established him or her as an expert? I’m willing to bet you’ll be more interested to listen after learning something compelling about the speaker. Several years ago, Joshua Bell, one of the most accomplished violinists in the world, was playing a million dollar Stradivarius violin in a public subway. Despite the fact that people pay several hundred dollars to hear him in concert, hardly anyone paid attention that particular day in the subway. His beautiful music was the equivalent of a compelling story but it wasn’t enough to grab people’s attention. Do you think people would have stopped to listen if they knew he was one of the greatest violinists in the world and that he was playing a million dollar instrument? I’d bet you any amount of money that many, many more people would have paid attention to him and his music. James Bond enjoys a brand very few individuals can claim. Warren Buffett, Bill Clinton and a few others would need no introduction before giving a speech, but you and I do, so here are six tips for your intro when presenting to a group of any size: You write the introduction. Don’t leave this to chance because nobody knows you and your expertise like you do.Keep it short. An intro of 100-200 words is plenty because too long and it’s boring, but too short and you may omit something important.Make sure it’s audience-appropriate. There may be interesting things you’ve accomplished that have nothing to do with the talk so leave out those things.Include something personal. This allows audience members to connect with you on a personal level which invokes the principle of liking.Have a third party introduce you. You do this because someone else can say things about you that will sound like bragging if you say them.Make sure the introduction happens before the talk. Unlike the movies where the credits come later, you want people to feel compelled to listen before you even open your mouth.Talking about Bond as a model for speaking makes for a compelling headline but not everything he does will work for you and me. That’s the difference between movies and reality. So my advice is this; find out what the science says then diligently apply it and you’re sure to give a more persuasive presentation.

I read an article not too long ago that a friend passed along and felt compelled to share my thoughts about it. The article appeared in Forbes.com and was titled “Why Public Speakers Need To Copy James Bond.” That’s a compelling title for Bond fans and speakers alike – of which I’m both – so I got sucked in and read. The author’s piece was well written and compelling…unless you know something about the psychology of persuasion. The gist of the article was this – Bond movies open with compelling action-packed scenes, not the credits, to immediately hook moviegoers. Speakers should do the same by starting immediately with a compelling story. I wholeheartedly agree that a speaker starting with a good story hooks the audience but foregoing a brief introduction misses out on a golden opportunity to utilize the principle of authority which will make you more persuasive, according to the science of influence. Imagine going to a conference and getting ready to listen to a speaker you’ve never heard of before. Will you pay more or less attention if you quickly learn beforehand the speaker was the top salesperson in their organization, or had a doctorate, or was one of only a handful in the world who does what he/she does, or had some other fact that established him or her as an expert? I’m willing to bet you’ll be more interested to listen after learning something compelling about the speaker. Several years ago, Joshua Bell, one of the most accomplished violinists in the world, was playing a million dollar Stradivarius violin in a public subway. Despite the fact that people pay several hundred dollars to hear him in concert, hardly anyone paid attention that particular day in the subway. His beautiful music was the equivalent of a compelling story but it wasn’t enough to grab people’s attention. Do you think people would have stopped to listen if they knew he was one of the greatest violinists in the world and that he was playing a million dollar instrument? I’d bet you any amount of money that many, many more people would have paid attention to him and his music. James Bond enjoys a brand very few individuals can claim. Warren Buffett, Bill Clinton and a few others would need no introduction before giving a speech, but you and I do, so here are six tips for your intro when presenting to a group of any size: You write the introduction. Don’t leave this to chance because nobody knows you and your expertise like you do.Keep it short. An intro of 100-200 words is plenty because too long and it’s boring, but too short and you may omit something important.Make sure it’s audience-appropriate. There may be interesting things you’ve accomplished that have nothing to do with the talk so leave out those things.Include something personal. This allows audience members to connect with you on a personal level which invokes the principle of liking.Have a third party introduce you. You do this because someone else can say things about you that will sound like bragging if you say them.Make sure the introduction happens before the talk. Unlike the movies where the credits come later, you want people to feel compelled to listen before you even open your mouth.Talking about Bond as a model for speaking makes for a compelling headline but not everything he does will work for you and me. That’s the difference between movies and reality. So my advice is this; find out what the science says then diligently apply it and you’re sure to give a more persuasive presentation.Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”.As noted last week; Dr. Cialdini has a new book coming out that he’s coauthored with Steve Martin and Noah Goldstein, Ph.D. The book is called The Small Big and can be pre-ordered here.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- …

- 128

- Next Page »