Written by Jessica Hamzelou for New Scientist Magazine

Written by Jessica Hamzelou for New Scientist Magazine

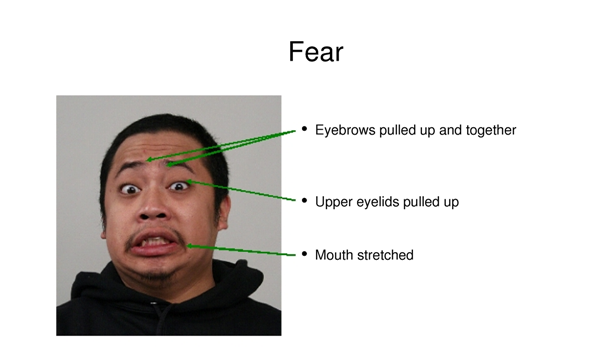

Wide eyes and mouth agape – you might think a fearful face is easy to recognize. That doesn’t seem to be the case for people who repeatedly commit antisocial offences. For the first time, training offenders to better read facial expressions has reduced violent crime.

The computer-based training – which only requires one person and a laptop to administer – is a promising new lead for managing antisocial behavior.

Under UK law, such behavior is defined as that which causes harassment, alarm or distress to another person, and includes violent crime, theft and criminal damage. People that repeatedly engage in this kind of behavior, with scant regard for those they hurt, are described as having antisocial personality disorder by the American Psychological Association.

“People tend to think that children who show antisocial behaviors are just criminals,” says Stephane de Brito at the University of Birmingham, UK. “But if these behaviors persist, they are at an increased risk of developing so many problems, such as psychotic illness, depression and substance abuse.”

In an effort to avoid this, children can be monitored and receive training from youth offender services. Other approaches target schools with anti-bullying programs, or offer support to parents. “There’s a lot done, and a lot of money is invested, but the programs are not having as much success as one would hope for,” says Stephanie van Goozen, a biological psychologist at Cardiff University in Wales.

Reading Faces

Van Goozen and her colleagues decided to try a different approach. The team turned to the psychological theory that people who harm others may do so because they can’t tell that their victim is distressed. Research has shown that both adult psychopaths and children diagnosed with “conduct disorder”, which is associated with antisocial behavior, struggle to recognize fear in the faces of other people.

When these children engage in behavior that is unpleasant or causes pain, they can’t tell that that the other person is suffering, so feel no need to correct their behavior, says van Goozen.

To find out if learning to recognize emotions would help these children to rein in their behavior, van Goozen’s team used a computer-based program that teaches people to recognize facial expressions. The system was originally developed by a team in the US to help people with brain injuries relearn the rules of social interactions.

They trained half of a group of 50 boys who had been convicted of a crime to recognize happiness, sadness, fear and anger in facial expressions. Each participant was aged between 12 and 18, and completed a total of between 7 and 9 hours of training over two or three sessions. “Gradually you teach people to pay attention to the right signals in the face, such as the eyes and the mouth – the things that tell you how intensely people feel,” says van Goozen. Her team also made a note of the crimes that all the boys had committed in the past, and those that were committed in the six months following training.

The team found that boys who received training significantly improved in their ability to recognize fear, anger and sadness in others’ faces, while those who had no training did not. Moreover, while all of the participants committed fewer offences than in the six months before the training – probably because they were closely monitored – in those who’d had training the crimes were significantly less violent and severe, and tended to involve theft rather than physical aggression. It is the first time that emotion training has been found to affect real-world crime.

Costly Crime

“It’s an important study,” says Richard Rowe, a psychologist who specializes in antisocial behavior at Sheffield University in the UK. While it is too early to make policy decisions based on one relatively small study, he says the findings represent an exciting new lead.

One advantage is the technique’s low cost. Antisocial behavior is expensive – by the age of 28, those who have engaged in it persistently from age 10 can end up costing society around 10 times more than those without a similar history, due to lost productivity as well as education and criminal justice system costs.

Money is currently spent on initiatives like support programs for the parents of offenders, but these tend to work best in families with the least problems. “My issue is that these programs might work in some kids but they don’t work in all kids, and they particularly don’t work in kids that need it most,” says van Goozen.

Van Goozen’s technique seems promising and low-cost, says Rowe. “All you need is one person and a laptop,” says van Goozen, who now plans to test the program in more young people, as well as children as young as 4 who might be at risk of developing antisocial behavior, because they have been abused, for example. She thinks it could work in adults too, given the success of similar training programs aimed at adults with brain injury in the US.

Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”.

Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”. The perceived trustworthiness of an inmate’s face may determine the severity of the sentence he receives, according to new research using photos and sentencing data for inmates in the state of Florida. The research, published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, reveals that inmates whose faces were rated as low in trustworthiness by independent observers were more likely to have received the death sentence than inmates whose faces were perceived as more trustworthy, even when the inmates were later exonerated of the crime.

The perceived trustworthiness of an inmate’s face may determine the severity of the sentence he receives, according to new research using photos and sentencing data for inmates in the state of Florida. The research, published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science, reveals that inmates whose faces were rated as low in trustworthiness by independent observers were more likely to have received the death sentence than inmates whose faces were perceived as more trustworthy, even when the inmates were later exonerated of the crime.