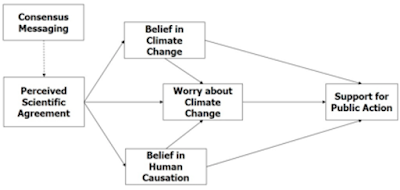

We are facing the next major extinction since the dinosaurs. Scientists have forewarned that a mere 2- degree Celsius rise in temperature on Earth could predict perilous implications such as drought, famine and human conflict. Countries will be underwater due to sea levels rising, and such high levels of drought means an inability to feed populations, generating mass migration or invasion of other countries. Not only are we rapidly approaching this 2- degree danger zone, but we will easily exceed it. A further 7- degree Celsius raise in temperature has the potential to trigger a similar effect which turned Venus into a 460- degree Celsius inhabitable environment. With such alarming warnings from scientists and researchers, it is our responsibility to protect our planet. Figure 1. Cowspiracy filmmakers Kip Anderson (right) andKeegan Kuhn (left)Environmental companies and activists have programmed society to believe the overuse of fossil fuels is the catalyst for climate change. The oil and gas industry is plastered over news and social media sites to be the most damaging environmental practise by humanity. Yet a ground- breaking independent documentary film, Cowspiracy, has exposed the sustainability secrets many environmental agencies have actively avoided. The filmmakers, Kip Anderson and Keegan Kuhn, uncovered an arguably intentional refusal to address the principle yet unforeseen cause of global warming: animal agriculture.Raising livestock produces more dangerous emissions than the entire transportation sector. Consequently, more greenhouse gases are produced from animal agriculture than from the exhausts of all cars, trucks, trains, boats and planes combined. On top of this, methane produced from cattle is 86x more destructive than carbon dioxide. Yet websites of the largest environmental agencies in America have almost no information on the detrimental effects of animal agriculture. The gateway belief model can be greatly applied to such scientific communication. When faced with uncertainty individuals tend to turn to experts for guidance, such as environmental agencies. This guidance is viewed as a consensus, and thus regarded as correct. Therefore, if fossil fuels are noted as the most damaging cause of climate change; the public will believe this as factual. The model also explains that if organisations portrayed animal agriculture as the leading issue, individual perceptions will follow, leading to a greater impact to reduce global warming. In summary, if environmental organisations portrayed animal agriculture as the primary cause of climate change, the public will comply to reduce the effects of greenhouse gases, deforestation and global warming. Agencies simply need to address the impact of animal agriculture. So why haven’t they?

Figure 1. Cowspiracy filmmakers Kip Anderson (right) andKeegan Kuhn (left)Environmental companies and activists have programmed society to believe the overuse of fossil fuels is the catalyst for climate change. The oil and gas industry is plastered over news and social media sites to be the most damaging environmental practise by humanity. Yet a ground- breaking independent documentary film, Cowspiracy, has exposed the sustainability secrets many environmental agencies have actively avoided. The filmmakers, Kip Anderson and Keegan Kuhn, uncovered an arguably intentional refusal to address the principle yet unforeseen cause of global warming: animal agriculture.Raising livestock produces more dangerous emissions than the entire transportation sector. Consequently, more greenhouse gases are produced from animal agriculture than from the exhausts of all cars, trucks, trains, boats and planes combined. On top of this, methane produced from cattle is 86x more destructive than carbon dioxide. Yet websites of the largest environmental agencies in America have almost no information on the detrimental effects of animal agriculture. The gateway belief model can be greatly applied to such scientific communication. When faced with uncertainty individuals tend to turn to experts for guidance, such as environmental agencies. This guidance is viewed as a consensus, and thus regarded as correct. Therefore, if fossil fuels are noted as the most damaging cause of climate change; the public will believe this as factual. The model also explains that if organisations portrayed animal agriculture as the leading issue, individual perceptions will follow, leading to a greater impact to reduce global warming. In summary, if environmental organisations portrayed animal agriculture as the primary cause of climate change, the public will comply to reduce the effects of greenhouse gases, deforestation and global warming. Agencies simply need to address the impact of animal agriculture. So why haven’t they? Figure 2. The gateway belief model demonstrating the pathway for acceptance of climate change.The simple suggestion would be to promote veganism and condense meat production. Yet recent statistics show that only 2% of the UK population and 0.5% of the USA population are vegans. To promote the reduction of meat consumption would impact over 95% of the population, and as such seems an unlikely request from environmental charities. These organisations are businesses, who need to ensure a reliable source of funding. Greenpeace is the largest environmental agency with an estimated $360 million global empire. For this reason, the public is advised to occasionally change their daily routine, for example through recycling and driving less, so they are lead to believe they are helping the environment. Whilst to some extent this is true, they are ignoring the primary cause of global warming. Agencies know that turning vegetarian or vegan is less achievable. Therefore, to sustain donations and interest from the public, animal agriculture is discounted and climate change is attributed to less demanding tasks, such as saving water and recycling plastic.

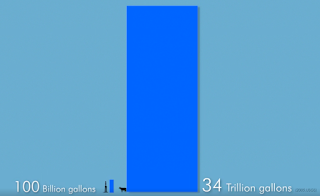

Figure 2. The gateway belief model demonstrating the pathway for acceptance of climate change.The simple suggestion would be to promote veganism and condense meat production. Yet recent statistics show that only 2% of the UK population and 0.5% of the USA population are vegans. To promote the reduction of meat consumption would impact over 95% of the population, and as such seems an unlikely request from environmental charities. These organisations are businesses, who need to ensure a reliable source of funding. Greenpeace is the largest environmental agency with an estimated $360 million global empire. For this reason, the public is advised to occasionally change their daily routine, for example through recycling and driving less, so they are lead to believe they are helping the environment. Whilst to some extent this is true, they are ignoring the primary cause of global warming. Agencies know that turning vegetarian or vegan is less achievable. Therefore, to sustain donations and interest from the public, animal agriculture is discounted and climate change is attributed to less demanding tasks, such as saving water and recycling plastic. Figure 3. The proportional representation of gallons of water used for hydraulic fracking (left) compared to animal agriculture (right) per year in AmericaWhilst climate change is still overlooked by many, our rapidly overcrowded planet must remain sustainable. Leaving the shower on constantly for two months is the equivalent to making one hamburger. Cowspiracy was able to uncover the controversial truth about the damaging effects of animal agriculture, leading to the film backing and funding being dropped. In the last 20 years in Brazil, where deforestation has resulted in an acre of land being cut down every six seconds, 2,100 activists have been killed trying to unravel these sustainability secrets. Animal agriculture is the primary cause of climate change, and whilst environmental agencies have concealed this factor to keep public interest, it must be addressed in order to avert the effects of global warming.References: Van der Linden, S. L., Leiserowitz, A. A., Feinberg, G. D., & Maibach, E. W. (2015). The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: experimental evidence. Plos One, 10(2), e0118489.

Figure 3. The proportional representation of gallons of water used for hydraulic fracking (left) compared to animal agriculture (right) per year in AmericaWhilst climate change is still overlooked by many, our rapidly overcrowded planet must remain sustainable. Leaving the shower on constantly for two months is the equivalent to making one hamburger. Cowspiracy was able to uncover the controversial truth about the damaging effects of animal agriculture, leading to the film backing and funding being dropped. In the last 20 years in Brazil, where deforestation has resulted in an acre of land being cut down every six seconds, 2,100 activists have been killed trying to unravel these sustainability secrets. Animal agriculture is the primary cause of climate change, and whilst environmental agencies have concealed this factor to keep public interest, it must be addressed in order to avert the effects of global warming.References: Van der Linden, S. L., Leiserowitz, A. A., Feinberg, G. D., & Maibach, E. W. (2015). The scientific consensus on climate change as a gateway belief: experimental evidence. Plos One, 10(2), e0118489.

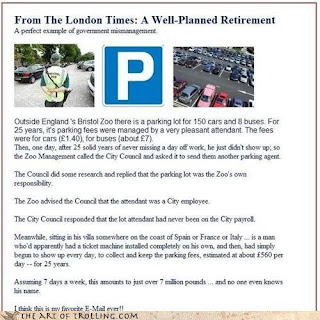

The Bristol Zoo parking attendant

If you are from Bristol or have any friends or family, you will have probably heard about the Bristol Zoo attendant and his cunning scheme to make money, through exploiting the norms of the people around, and obedience to authority.

If you are from Bristol or have any friends or family, you will have probably heard about the Bristol Zoo attendant and his cunning scheme to make money, through exploiting the norms of the people around, and obedience to authority.  Whether this is a true story or not is debatable, however, many people still talk about it, and it got me thinking about how this could be done anywhere and be successful.Bristol Zoo is one of many attractions in Bristol, homing animals of many species and sizes, from Jock the silverback to small insects and bugs. A lovely day out for anyone! There is a car park right outside of the Zoo which gets filled promptly, or an overflow carpark in peak times which is situated on ‘The Downs’, a large greenery area of land sitting in the middle of the City (right next to the Zoo). Story has it, that a very clever man in his 50’s put on a uniform resembling a parking attendant, got himself some equipment that enabled him to print tickets on the spot and walked around the car park, collecting money from visitors and accrediting them a ticket in return. You can imagine just how much this man would have received in a day, charging a few pounds per day for hundreds of cars coming and going. Until one day.. He wasn’t there, anxious visitors asking workers at the Zoo, where to pay for a ticket so they wouldn’t get a fine. They had no idea of course, where their ticket man had gone and why he had not showed up for work! So the workers at Bristol Zoo rang up Bristol City Council and enquired into why their worker (employed by the council) hadn’t showed up, or why they hadn’t sent a replacement. They replied that they do not organise the workers for the carpark at the Zoo and had no records of anyone working for them. Reality struck when they had realised that a stranger had (for about 10 years) been manipulating the system and collecting money for himself. Now he had disappeared and no record of him anyway, he would probably be as far away from the Zoo as possible, with an enormous wad of cash!The aspects of this tale that strike me the most is obedience to authority. Every single person who parked in that car park gave this man money because he had simply placed a uniform on that resembled an authority figure. He looked right, had the appropriate equipment and a name badge. Why would anyone question his authority? In addition, the social norms people have about obedience to authority, and having to pay for parking meant that everyone followed the crowd in a way. After parking in a space, most drivers probably looked around and saw a man who was approached by other likeminded people, taking their money and given a ticket in response. If anyone questioned what the appropriate behaviour was, they would look for social proof and engage in the behaviours of other people around them. Moreover, visitors are probably preoccupied with the fear of getting a parking ticket, or the stress of controlling their excited children, that contributes to the success this man had. Zimbardo (1973) conducted a very famous Standford prison experiment that demonstrated the power of obedience to authority. By assigning two groups of people randomly to the position of a guard or prisoner, and by having the prison officers wear uniform, this created a sense of power between the two groups, and prisoners as a result of social norms would comply with their requests, (similar to visitors to Bristol zoo, complying with rules and abiding with the social norms.)Other experiments have demonstrated that the power of uniform can affect peoples decisions. Bickman (1971) found people were more likely to comply with individuals who were in a uniform, and the type of uniform also influenced how people conformed. In the case of the Bristol Zoo attendant, the uniform he was dressed in created a sense of authority and people would naturally comply accordingly. References:Bickman, L. (1971). The effect of different uniforms on obedience in field situations. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association.Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Reviews, 9(1-17).

Whether this is a true story or not is debatable, however, many people still talk about it, and it got me thinking about how this could be done anywhere and be successful.Bristol Zoo is one of many attractions in Bristol, homing animals of many species and sizes, from Jock the silverback to small insects and bugs. A lovely day out for anyone! There is a car park right outside of the Zoo which gets filled promptly, or an overflow carpark in peak times which is situated on ‘The Downs’, a large greenery area of land sitting in the middle of the City (right next to the Zoo). Story has it, that a very clever man in his 50’s put on a uniform resembling a parking attendant, got himself some equipment that enabled him to print tickets on the spot and walked around the car park, collecting money from visitors and accrediting them a ticket in return. You can imagine just how much this man would have received in a day, charging a few pounds per day for hundreds of cars coming and going. Until one day.. He wasn’t there, anxious visitors asking workers at the Zoo, where to pay for a ticket so they wouldn’t get a fine. They had no idea of course, where their ticket man had gone and why he had not showed up for work! So the workers at Bristol Zoo rang up Bristol City Council and enquired into why their worker (employed by the council) hadn’t showed up, or why they hadn’t sent a replacement. They replied that they do not organise the workers for the carpark at the Zoo and had no records of anyone working for them. Reality struck when they had realised that a stranger had (for about 10 years) been manipulating the system and collecting money for himself. Now he had disappeared and no record of him anyway, he would probably be as far away from the Zoo as possible, with an enormous wad of cash!The aspects of this tale that strike me the most is obedience to authority. Every single person who parked in that car park gave this man money because he had simply placed a uniform on that resembled an authority figure. He looked right, had the appropriate equipment and a name badge. Why would anyone question his authority? In addition, the social norms people have about obedience to authority, and having to pay for parking meant that everyone followed the crowd in a way. After parking in a space, most drivers probably looked around and saw a man who was approached by other likeminded people, taking their money and given a ticket in response. If anyone questioned what the appropriate behaviour was, they would look for social proof and engage in the behaviours of other people around them. Moreover, visitors are probably preoccupied with the fear of getting a parking ticket, or the stress of controlling their excited children, that contributes to the success this man had. Zimbardo (1973) conducted a very famous Standford prison experiment that demonstrated the power of obedience to authority. By assigning two groups of people randomly to the position of a guard or prisoner, and by having the prison officers wear uniform, this created a sense of power between the two groups, and prisoners as a result of social norms would comply with their requests, (similar to visitors to Bristol zoo, complying with rules and abiding with the social norms.)Other experiments have demonstrated that the power of uniform can affect peoples decisions. Bickman (1971) found people were more likely to comply with individuals who were in a uniform, and the type of uniform also influenced how people conformed. In the case of the Bristol Zoo attendant, the uniform he was dressed in created a sense of authority and people would naturally comply accordingly. References:Bickman, L. (1971). The effect of different uniforms on obedience in field situations. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association.Haney, C., Banks, W. C., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison. Naval Research Reviews, 9(1-17).

Remember the ALS Ice Bucket Storm?

I will never forget the summer of 2014. I graduated high school, was eagerly anticipating my next big adventure at university, and had my brother pour a most debilitatingly ice-cold bucket of water over my head in the name of Lou Gehrig’s disease. A social media frenzy had taken over – the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. The exact origins of the fad are unknown but the received wisdom is that it started with a Boston College student who was diagnosed with the disease in 2012. The challenge entailed the simple act of pouring an ice cold bucket of water over one’s head, uploading a video of the act to social media, making a donation to ALS research, and then nominating three other friends to take on the very same challenge. As of August 2014, The ALS Association had received $31.5 million in donations compared to $1.9 million during the same time period (July 29 to August 20) the previous year (Deighton, 2014) and the Ice Bucket Challenge had over 2.4 million tagged videos on Facebook (Stampler, 2014). But how exactly was this social media fad so effective in influencing hordes of individuals to donate towards ALS research? A simple explanation could have been its timing. The challenge was fortuitously instigated at the start of the summer, getting underway in June 2014 and peaking in August 2014. Obviously, high summer is a more suitable time to perform the act of tipping an ice-cold bucket of water over the head than, say, December. However, timing alone could not possibly account for such a social media frenzy and the sheer magnitude of donations that came in. Perhaps psychology can shed some light?1. Perceptual Salience. Could the influence of the ice bucket challenge have had its roots in our perceptual processes? Attention research has shown that the kind of stimuli that capture our gaze is the appearance of new visual objects (Yantis, 1993; Yantis & Jonides, 1996) and objects that are interesting (Elazary & Itty, 2008). Indeed, the ice-bucket challenge presents viewers with both a novel and visually interesting stimulus:-a campaign of this kind had never been implemented before and the nature of the challenge was peculiar. Thus, the novelty and uniqueness of the challenge was likely implicated in it becoming almost hysterically popular with the consequence being the number of donations that came in. 2. Commitment and ConsistencyAccording to Cialdini, one of the most effective ‘weapons of influence’ is our “obsessive desire to be consistent and to appear consistent with what we have already done” (1984 p 37). Compelling evidence for this comes from psychologist Thomas Moriarty who staged thefts on Jones Beach in New York. This study revealed that participants who had previously committed to protecting a confederate’s belongings after being requested to do so were much more likely to intervene during the theft with behaviours including chasing and stopping the thief, restraining the thief physically or even demanding an explanation for the theft (Moriarty, 1975). However, this should not be surprising as psychologist have long understood the power of consistency in motivating human behaviour. For example, Leon Festinger’s (1962) “Effort justification” is one explanation as to why participants of the ice bucket challenge are likely to have donated. One of the most classic examples of effort justification is Aronson and Mills’s (1952) study on a group of young women who volunteered to join a discussion group on the topic of the psychology of sex. The women were placed in a mild-embarrassment condition which involved reading aloud sex-related words (e.g. prostitute or virgin), a severe-embarrassment condition which involved saying highly sexual words (e.g. f*ck or c*ck) and a control group who did not read sex related words at all. All subjects then listened to a recording of a dull discussion about sexual behaviour in animals. When asked to rate the group and its members, the severe-embarrassment group’s ratings were significantly higher whereas control and mild-embarrassment groups did not differ. Aronson and Mills concluded that this was because those whose initiation process was more difficult (embarrassment equalling effort), had to increase their subjective value of the discussion group to resolve their subsequent cognitive dissonance. Stripping into one’s bathing suit, preparing a bucket of ice-cold water, asking one friend to pour the bucket over your head while another films it being poured all over you only for you to then upload it onto social media and to consequently challenge three other friends to do exactly the same thing in the name of ALS research is an effortful and uncomfortable process to say the least. Thus, it makes sense to assume the participants of the Ice Bucket Challenge – who persisted in this effortful task for ALS – donated for the same reason Moriarty’s participants chased the thief and Aronson and Mill’s participants rated their groups so highly – “to be and to appear consistent with what they had already done”.3. Public ImageA further explanation for the success of the ice bucket challenge could have been the communal and innately public nature of it. Psychologists are well aware of how desire to maintain a good reputation is also a powerful ‘weapon of influence’. Results from experimental economic games have shown that manipulating reputational opportunities affects prosocial behaviour and that opportunities for reputation formation can play an important role in sustaining cooperation and prosocial behaviour (Hayley & Fessler, 2005). The nature of the challenge allowed those taking part to publicly display social responsibility through charitable behaviour, and cooperation through accepting the challenge from a friend. Thus, desire to maintain a good reputation is likely to have contributed to the viral spread of the challenge and the magnitude of donations that came in. 4. Use of Role ModelsPerhaps one of the most powerful ‘weapon of influence’ utilised by this campaign was its involvement of celebrities. The influence of celebrities in the 21st century extends far beyond the traditional domain of the entertainment sector. They are important figures in campaigns for social change and the global internet is one of the major drivers of this phenomenon (Choi & Berger, 2010). Celebrities such as Oprah, Selena Gomez and Taylor Swift undertook the challenge. Perhaps more powerfully the challenge was not liable solely for celebrities but famous athletes, leading businessmen and influential entrepreneurs who too took part in the challenge. Lebron James, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg to name a few. For many, these individuals are important role models and research has shown how influential role models can be in dictating our behaviour. Role models can strongly influence purchase intentions and behaviour (Martin & Bush, 2000). An individual’s role model has even been implicated in the prediction of women’s career choices (Quimby & Santis, 2006). Thus, role models are looked up to by others and their actions are emulated by those admirers. The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge is evidence of this. For all those individuals on social media, seeing the singer or athlete they admire most donate and dedicate themselves to ALS was likely a very strong motivation to play a part in spreading the message and fundraising for the cause. But what became of it? As it turns out the funds raised from the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge helped identify a new gene associated with the disease the following year. Although only present in 3% of ALS cases, the NEK1 gene was found present in both inherited and sporadic forms of the disease which researchers believe will provide them a new target for the development of possible treatments (Cirulli et al., 2015). However small this breakthrough may seem, the ALS Ice Bucket challenge highlights two very important things: first, that working together we can bring about real change and awareness of social issues and second, never to underestimate the power of influence in dictating human behaviour. Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 177.Choi, C. J., & Berger, R. (2010). Ethics of celebrities and their increasing influence in 21st century society. Journal of business ethics, 91, 313-318.Cialdini, R. B. (1987). Influence (Vol. 3). A. Michel.Cirulli, E. T., Lasseigne, B. N., Petrovski, S., Sapp, P. C., Dion, P. A., Leblond, C. S., … & Ren, Z. (2015). Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science, 347, 1436-1441.Deighton, J. (2014, August 20). Why the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge is a Social Media Blockbuster. Retrieved from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/why-the-als-ice-bucket-challenge-is-a-social-media-blockbuster.Elazary, L., & Itti, L. (2008). Interesting objects are visually salient. Journal of vision, 8, 3-3.Haley, K. J., & Fessler, D. M. (2005). Nobody’s watching?: Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evolution and Human behavior, 26, 245-256.Moriarty, T. (1975). Crime, commitment, and the responsive bystander: Two field experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 370.Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford university press.Yantis, S. (1993). Stimulus-driven attention capture. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2, 156–161.Yantis, S., & Jonides, J. (1996). Attentional capture by abrupt onsets: New perceptual objects or visual masking? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 22, 1505–1513.Quimby, J. L., & Santis, A. M. (2006). The influence of role models on women’s career choices. The Career Development Quarterly, 54, 297-306. Stampler, L. (2014, August 15) This Is How Many Ice Bucket Challenge Videos People Have Posted on Facebook. Receieved from http://time.com/3117501/als-ice-bucket-challenge-videos-on-facebook/.

As of August 2014, The ALS Association had received $31.5 million in donations compared to $1.9 million during the same time period (July 29 to August 20) the previous year (Deighton, 2014) and the Ice Bucket Challenge had over 2.4 million tagged videos on Facebook (Stampler, 2014). But how exactly was this social media fad so effective in influencing hordes of individuals to donate towards ALS research? A simple explanation could have been its timing. The challenge was fortuitously instigated at the start of the summer, getting underway in June 2014 and peaking in August 2014. Obviously, high summer is a more suitable time to perform the act of tipping an ice-cold bucket of water over the head than, say, December. However, timing alone could not possibly account for such a social media frenzy and the sheer magnitude of donations that came in. Perhaps psychology can shed some light?1. Perceptual Salience. Could the influence of the ice bucket challenge have had its roots in our perceptual processes? Attention research has shown that the kind of stimuli that capture our gaze is the appearance of new visual objects (Yantis, 1993; Yantis & Jonides, 1996) and objects that are interesting (Elazary & Itty, 2008). Indeed, the ice-bucket challenge presents viewers with both a novel and visually interesting stimulus:-a campaign of this kind had never been implemented before and the nature of the challenge was peculiar. Thus, the novelty and uniqueness of the challenge was likely implicated in it becoming almost hysterically popular with the consequence being the number of donations that came in. 2. Commitment and ConsistencyAccording to Cialdini, one of the most effective ‘weapons of influence’ is our “obsessive desire to be consistent and to appear consistent with what we have already done” (1984 p 37). Compelling evidence for this comes from psychologist Thomas Moriarty who staged thefts on Jones Beach in New York. This study revealed that participants who had previously committed to protecting a confederate’s belongings after being requested to do so were much more likely to intervene during the theft with behaviours including chasing and stopping the thief, restraining the thief physically or even demanding an explanation for the theft (Moriarty, 1975). However, this should not be surprising as psychologist have long understood the power of consistency in motivating human behaviour. For example, Leon Festinger’s (1962) “Effort justification” is one explanation as to why participants of the ice bucket challenge are likely to have donated. One of the most classic examples of effort justification is Aronson and Mills’s (1952) study on a group of young women who volunteered to join a discussion group on the topic of the psychology of sex. The women were placed in a mild-embarrassment condition which involved reading aloud sex-related words (e.g. prostitute or virgin), a severe-embarrassment condition which involved saying highly sexual words (e.g. f*ck or c*ck) and a control group who did not read sex related words at all. All subjects then listened to a recording of a dull discussion about sexual behaviour in animals. When asked to rate the group and its members, the severe-embarrassment group’s ratings were significantly higher whereas control and mild-embarrassment groups did not differ. Aronson and Mills concluded that this was because those whose initiation process was more difficult (embarrassment equalling effort), had to increase their subjective value of the discussion group to resolve their subsequent cognitive dissonance. Stripping into one’s bathing suit, preparing a bucket of ice-cold water, asking one friend to pour the bucket over your head while another films it being poured all over you only for you to then upload it onto social media and to consequently challenge three other friends to do exactly the same thing in the name of ALS research is an effortful and uncomfortable process to say the least. Thus, it makes sense to assume the participants of the Ice Bucket Challenge – who persisted in this effortful task for ALS – donated for the same reason Moriarty’s participants chased the thief and Aronson and Mill’s participants rated their groups so highly – “to be and to appear consistent with what they had already done”.3. Public ImageA further explanation for the success of the ice bucket challenge could have been the communal and innately public nature of it. Psychologists are well aware of how desire to maintain a good reputation is also a powerful ‘weapon of influence’. Results from experimental economic games have shown that manipulating reputational opportunities affects prosocial behaviour and that opportunities for reputation formation can play an important role in sustaining cooperation and prosocial behaviour (Hayley & Fessler, 2005). The nature of the challenge allowed those taking part to publicly display social responsibility through charitable behaviour, and cooperation through accepting the challenge from a friend. Thus, desire to maintain a good reputation is likely to have contributed to the viral spread of the challenge and the magnitude of donations that came in. 4. Use of Role ModelsPerhaps one of the most powerful ‘weapon of influence’ utilised by this campaign was its involvement of celebrities. The influence of celebrities in the 21st century extends far beyond the traditional domain of the entertainment sector. They are important figures in campaigns for social change and the global internet is one of the major drivers of this phenomenon (Choi & Berger, 2010). Celebrities such as Oprah, Selena Gomez and Taylor Swift undertook the challenge. Perhaps more powerfully the challenge was not liable solely for celebrities but famous athletes, leading businessmen and influential entrepreneurs who too took part in the challenge. Lebron James, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg to name a few. For many, these individuals are important role models and research has shown how influential role models can be in dictating our behaviour. Role models can strongly influence purchase intentions and behaviour (Martin & Bush, 2000). An individual’s role model has even been implicated in the prediction of women’s career choices (Quimby & Santis, 2006). Thus, role models are looked up to by others and their actions are emulated by those admirers. The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge is evidence of this. For all those individuals on social media, seeing the singer or athlete they admire most donate and dedicate themselves to ALS was likely a very strong motivation to play a part in spreading the message and fundraising for the cause. But what became of it? As it turns out the funds raised from the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge helped identify a new gene associated with the disease the following year. Although only present in 3% of ALS cases, the NEK1 gene was found present in both inherited and sporadic forms of the disease which researchers believe will provide them a new target for the development of possible treatments (Cirulli et al., 2015). However small this breakthrough may seem, the ALS Ice Bucket challenge highlights two very important things: first, that working together we can bring about real change and awareness of social issues and second, never to underestimate the power of influence in dictating human behaviour. Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 177.Choi, C. J., & Berger, R. (2010). Ethics of celebrities and their increasing influence in 21st century society. Journal of business ethics, 91, 313-318.Cialdini, R. B. (1987). Influence (Vol. 3). A. Michel.Cirulli, E. T., Lasseigne, B. N., Petrovski, S., Sapp, P. C., Dion, P. A., Leblond, C. S., … & Ren, Z. (2015). Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science, 347, 1436-1441.Deighton, J. (2014, August 20). Why the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge is a Social Media Blockbuster. Retrieved from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/why-the-als-ice-bucket-challenge-is-a-social-media-blockbuster.Elazary, L., & Itti, L. (2008). Interesting objects are visually salient. Journal of vision, 8, 3-3.Haley, K. J., & Fessler, D. M. (2005). Nobody’s watching?: Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evolution and Human behavior, 26, 245-256.Moriarty, T. (1975). Crime, commitment, and the responsive bystander: Two field experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 370.Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford university press.Yantis, S. (1993). Stimulus-driven attention capture. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2, 156–161.Yantis, S., & Jonides, J. (1996). Attentional capture by abrupt onsets: New perceptual objects or visual masking? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 22, 1505–1513.Quimby, J. L., & Santis, A. M. (2006). The influence of role models on women’s career choices. The Career Development Quarterly, 54, 297-306. Stampler, L. (2014, August 15) This Is How Many Ice Bucket Challenge Videos People Have Posted on Facebook. Receieved from http://time.com/3117501/als-ice-bucket-challenge-videos-on-facebook/.