The Snickers chocolate bar advertisement campaign is well-known. You have probably seen television or poster advertisements online and in public areas.Why is it so successful? The consistent repetition of the simple phrase; ‘you’re not you when you’re hungry’ acts as a constant reminder of the branding that Snickers aims to create. Suggesting that Snickers ‘satisfies’. This makes the message easier to remember and therefore recall at a later date. The availability heuristic suggests that this may make individuals place more importance on the message and therefore the Snickers brand because they are using this ease of retrieval as an indicator of its overall importance. Previous research has found evidence to support this availability heuristic in many different topic areas. For example, do you think there are more words that start with the letter ‘K’ or have the letter ‘K’ as the third letter?Most of you probably opted for the first choice and thought that more words start with ‘K’. This is because these words come to mind more readily and therefore you think there are more of them. When in fact, the latter option is the correct one, but these words are often harder to think of and so you place less importance on them and think there are fewer (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). This is an example of the availability heuristic and can be applied to many advertisement campaigns, such as with Snickers.The agenda setting theory develops this idea further. Studies have found that when a form of the availability heuristic is applied to other settings, such as the news, people perceive the importance of issues by how much they are repeated or emphasised (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). When items and ideas easily come to mind, due to them being repeated and emphasised persistently, we think they are more important or true! In this case, because the snickers slogan easily comes to mind we place more emphasis on it and believe it to be true, making us more likely to invest in the advertisement idea and ultimately buy the chocolate bar. In summary, you are what you expose yourself to. According to this theory, the more you expose yourself to the Snickers adverts, ultimately the more likely you are to buy the chocolate bar.The mere exposure effect (Zajonc, 1968) suggests that this frequent repetition is effective advertising because those items which we are exposed to more frequently we will later deem to be more favourable or desirable. This is the power of familiarity and suggests that the more familiar and frequently seen the advertisements and Snicker chocolate bar are, the more popular and desirable they will become.The television video advertisements above demonstrate an individual in each acting negatively out of character, who then returns to normal after eating a Snickers. The positive change and outcome in behaviour demonstrated by these individuals is desirable for others to also want to achieve. From a behaviourism perspective, Skinner (1958) may have suggested that this is a form of reinforcement of the behaviour created by eating the Snickers. This type of reinforcement makes the behaviour more likely to be repeated by others following observation, through operant conditioning.Bandura, Ross and Ross (1986) demonstrated the behaviourism perspective through social learning theory with their bobo doll experiment. Children who observed an adult displaying aggressive behaviour were then more likely to display an increased amount of aggressive behaviour, when they became frustrated, whilst interacting with the bobo doll. Ultimately this implies that people learn by observing others. Similar results were found when children watched a real-life model or a film-mediated model (Bandura, Ross & Ross, 1963). The same can therefore be applied to advertisements. People here are learning that these individuals behaviour and outcomes are preferable once they have eaten the Snickers chocolate bar. This vicarious reinforcement makes other individuals watching the advertisement want to emulate and reproduce the behaviour and success the have observed by buying and eating the Snickers chocolate bar.Social Cognitive Theory

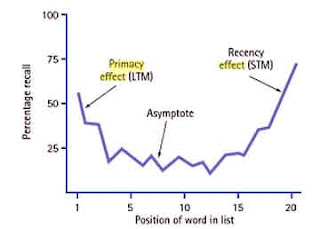

The consistent repetition of the simple phrase; ‘you’re not you when you’re hungry’ acts as a constant reminder of the branding that Snickers aims to create. Suggesting that Snickers ‘satisfies’. This makes the message easier to remember and therefore recall at a later date. The availability heuristic suggests that this may make individuals place more importance on the message and therefore the Snickers brand because they are using this ease of retrieval as an indicator of its overall importance. Previous research has found evidence to support this availability heuristic in many different topic areas. For example, do you think there are more words that start with the letter ‘K’ or have the letter ‘K’ as the third letter?Most of you probably opted for the first choice and thought that more words start with ‘K’. This is because these words come to mind more readily and therefore you think there are more of them. When in fact, the latter option is the correct one, but these words are often harder to think of and so you place less importance on them and think there are fewer (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). This is an example of the availability heuristic and can be applied to many advertisement campaigns, such as with Snickers.The agenda setting theory develops this idea further. Studies have found that when a form of the availability heuristic is applied to other settings, such as the news, people perceive the importance of issues by how much they are repeated or emphasised (Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). When items and ideas easily come to mind, due to them being repeated and emphasised persistently, we think they are more important or true! In this case, because the snickers slogan easily comes to mind we place more emphasis on it and believe it to be true, making us more likely to invest in the advertisement idea and ultimately buy the chocolate bar. In summary, you are what you expose yourself to. According to this theory, the more you expose yourself to the Snickers adverts, ultimately the more likely you are to buy the chocolate bar.The mere exposure effect (Zajonc, 1968) suggests that this frequent repetition is effective advertising because those items which we are exposed to more frequently we will later deem to be more favourable or desirable. This is the power of familiarity and suggests that the more familiar and frequently seen the advertisements and Snicker chocolate bar are, the more popular and desirable they will become.The television video advertisements above demonstrate an individual in each acting negatively out of character, who then returns to normal after eating a Snickers. The positive change and outcome in behaviour demonstrated by these individuals is desirable for others to also want to achieve. From a behaviourism perspective, Skinner (1958) may have suggested that this is a form of reinforcement of the behaviour created by eating the Snickers. This type of reinforcement makes the behaviour more likely to be repeated by others following observation, through operant conditioning.Bandura, Ross and Ross (1986) demonstrated the behaviourism perspective through social learning theory with their bobo doll experiment. Children who observed an adult displaying aggressive behaviour were then more likely to display an increased amount of aggressive behaviour, when they became frustrated, whilst interacting with the bobo doll. Ultimately this implies that people learn by observing others. Similar results were found when children watched a real-life model or a film-mediated model (Bandura, Ross & Ross, 1963). The same can therefore be applied to advertisements. People here are learning that these individuals behaviour and outcomes are preferable once they have eaten the Snickers chocolate bar. This vicarious reinforcement makes other individuals watching the advertisement want to emulate and reproduce the behaviour and success the have observed by buying and eating the Snickers chocolate bar.Social Cognitive Theory The diagram above demonstrating the social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) provides insight into the behaviours. According to the theory behaviour that is observed creates an environment. The person observes other individuals abilities to perform certain behaviours and so they believe that they are also able to complete these behaviour and tasks. For example, eat a Snickers chocolate bar and improve their behaviour. This is referred to as self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977). Together the vertices of the triangle influence one another and the behaviour of eating a Snickers becomes more likely due to the advertisements in their environment. Both advertisement videos above depict an individual who is struggling to fit into their ingroup. They eventually manage to be accepted and adapt their behaviour once they have eaten a Snickers bar. This implies that the Snickers bar has enabled them to fit into their ingroup and identify with them once more. According to the social identity theory (Tajfel, 1981) individuals have a desire to obtain membership within their ingroup and associate with the group by adopting group norms. The videos therefore indicate that the Snicker bar helps individuals achieve this and so promotes the bar to the audience. When watching the two YouTube video advertisements above, consider; ‘Who says what, by what means, to whom?’ These are important principles when analysing advertisements and the embedded persuasion to purchase the product within them. The Yale Attitude Change Approach (Hovland, 1953) suggests that persuasion is influenced by 3 factors:The source (Who) – Within these videos well known figures, such as Mr Bean, played by Rowan Atkinson, are used. These celebrities represent individuals that people recognise, associate with and want to be like, altering subjective norms and therefore individuals intention for their behaviour. This is according to the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). Also, they are portrayed in ways that make them similar and relatable. This makes the source and overall advertisement have a greater impact and persuading influence on consumers to buy the Snickers chocolate bar. The Message (What it is) – According the primacy-recency effect (Murdock, 1962), the messages presented at the beginning and end are most likely to be remembered. The messages in the middle are most likely to be displaced and forgotten. This is often known as the serial position effect. Murdock (1962) asked participants to recall word lists consisting of 20 words. Murdock found that words were more often remembered if they appeared near the start or end of the word list, as displayed in the graph below.

The diagram above demonstrating the social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) provides insight into the behaviours. According to the theory behaviour that is observed creates an environment. The person observes other individuals abilities to perform certain behaviours and so they believe that they are also able to complete these behaviour and tasks. For example, eat a Snickers chocolate bar and improve their behaviour. This is referred to as self-efficacy (Bandura, 1977). Together the vertices of the triangle influence one another and the behaviour of eating a Snickers becomes more likely due to the advertisements in their environment. Both advertisement videos above depict an individual who is struggling to fit into their ingroup. They eventually manage to be accepted and adapt their behaviour once they have eaten a Snickers bar. This implies that the Snickers bar has enabled them to fit into their ingroup and identify with them once more. According to the social identity theory (Tajfel, 1981) individuals have a desire to obtain membership within their ingroup and associate with the group by adopting group norms. The videos therefore indicate that the Snicker bar helps individuals achieve this and so promotes the bar to the audience. When watching the two YouTube video advertisements above, consider; ‘Who says what, by what means, to whom?’ These are important principles when analysing advertisements and the embedded persuasion to purchase the product within them. The Yale Attitude Change Approach (Hovland, 1953) suggests that persuasion is influenced by 3 factors:The source (Who) – Within these videos well known figures, such as Mr Bean, played by Rowan Atkinson, are used. These celebrities represent individuals that people recognise, associate with and want to be like, altering subjective norms and therefore individuals intention for their behaviour. This is according to the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). Also, they are portrayed in ways that make them similar and relatable. This makes the source and overall advertisement have a greater impact and persuading influence on consumers to buy the Snickers chocolate bar. The Message (What it is) – According the primacy-recency effect (Murdock, 1962), the messages presented at the beginning and end are most likely to be remembered. The messages in the middle are most likely to be displaced and forgotten. This is often known as the serial position effect. Murdock (1962) asked participants to recall word lists consisting of 20 words. Murdock found that words were more often remembered if they appeared near the start or end of the word list, as displayed in the graph below. The most important message within the video advertisement is displayed at the end. This shows the Snicker chocolate bar, the slogan and the positive effects eating the bar has. According to this theory these are most likely to be remembered. As previously mentioned repetition amongst the whole Snickers advertising campaign for the key message is used. For example, the slogan ‘you’re not you when you’re hungry’ is repeated throughout. Hitler has said that a good propagandist technique ‘must confine itself to a few points and repeat them over and over again’. The campaign attempts to achieve this and ultimately increase liking and validity of the messages. The Audience (To whom) – The advertisements require limited prior knowledge and can therefore be understood easily by a wide audience. This encourages the audience to use the peripheral route to persuasion by paying limited attention, according to the Elaboration-Likelihood Model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The Elaboration-Likelihood Model

The most important message within the video advertisement is displayed at the end. This shows the Snicker chocolate bar, the slogan and the positive effects eating the bar has. According to this theory these are most likely to be remembered. As previously mentioned repetition amongst the whole Snickers advertising campaign for the key message is used. For example, the slogan ‘you’re not you when you’re hungry’ is repeated throughout. Hitler has said that a good propagandist technique ‘must confine itself to a few points and repeat them over and over again’. The campaign attempts to achieve this and ultimately increase liking and validity of the messages. The Audience (To whom) – The advertisements require limited prior knowledge and can therefore be understood easily by a wide audience. This encourages the audience to use the peripheral route to persuasion by paying limited attention, according to the Elaboration-Likelihood Model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). The Elaboration-Likelihood Model Alternatively, showing role-models achieve desired behaviour caused by eating the Snickers increases the audiences self-esteem and belief that they can also achieve this by eating the chocolate bar.

Alternatively, showing role-models achieve desired behaviour caused by eating the Snickers increases the audiences self-esteem and belief that they can also achieve this by eating the chocolate bar. Other advertisements, such as this image above, encourage people to use the peripheral route of persuasion. This is an advert containing an attractive person and the message is associated with positive ‘rewards’, such as those with sexual connotations. This is presented in such an eye-catching way that the audience will be unable to defend themselves from making these associations. This means that the audience is unlikely to process the information through thoughtful or careful thinking via the central route. Instead they will use the cues present in the advertisement and work on general impressions of the product. This is also due to the message of chocolate bars being relatively unimportant and so individuals will become cognitive misers, reducing cognitive effort by not elaborating or thinking in depth about the message. They are using system 1 or heuristic processing, which is fast, implicit and associative according to the heuristic-systematic model (Chaiken et al., 1989). This advertisement could also be described as a clever use of pictorial analogy, making the audience more likely to remember such an image. Other clever advertisements have also been created for the Snickers chocolate bar. For example, the image below provides a competition template, where Snickers is wrapped up using other chocolate bar wrappers. Below, we have the wrapping of the Bounty bar on the left and the Twix bar on the right.

Other advertisements, such as this image above, encourage people to use the peripheral route of persuasion. This is an advert containing an attractive person and the message is associated with positive ‘rewards’, such as those with sexual connotations. This is presented in such an eye-catching way that the audience will be unable to defend themselves from making these associations. This means that the audience is unlikely to process the information through thoughtful or careful thinking via the central route. Instead they will use the cues present in the advertisement and work on general impressions of the product. This is also due to the message of chocolate bars being relatively unimportant and so individuals will become cognitive misers, reducing cognitive effort by not elaborating or thinking in depth about the message. They are using system 1 or heuristic processing, which is fast, implicit and associative according to the heuristic-systematic model (Chaiken et al., 1989). This advertisement could also be described as a clever use of pictorial analogy, making the audience more likely to remember such an image. Other clever advertisements have also been created for the Snickers chocolate bar. For example, the image below provides a competition template, where Snickers is wrapped up using other chocolate bar wrappers. Below, we have the wrapping of the Bounty bar on the left and the Twix bar on the right.

Extreme situation template has also been used. Below this is displayed showing a Zebra chasing a Lion.

Extreme situation template has also been used. Below this is displayed showing a Zebra chasing a Lion. To briefly conclude, successful advertisements and their underlying persuasion and influence on the audience are rather more complex then they first appear!References: Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review, 84(2), 191.Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Vicarious reinforcement and imitative learning. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(6), 601.Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(1), 3.Chaiken, S., & Eagly, A. H. (1989). Heuristic and systematic information processing within and. Unintended thought, 212.Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion; psychological studies of opinion change.Murdock Jr, B. B. (1962). The serial position effect of free recall. Journal of experimental psychology, 64(5), 482.Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and persuasion (pp. 1-24). Springer New York.Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of communication, 57(1), 9-20.Skinner, B. F. (1958). Reinforcement today. American Psychologist, 13(3), 94.Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories: Studies in social psychology. CUP Archive.Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive psychology, 5(2), 207-232.Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9(2p2), 1.

To briefly conclude, successful advertisements and their underlying persuasion and influence on the audience are rather more complex then they first appear!References: Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 50(2), 179-211.Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review, 84(2), 191.Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Inc.Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Vicarious reinforcement and imitative learning. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(6), 601.Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1963). Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66(1), 3.Chaiken, S., & Eagly, A. H. (1989). Heuristic and systematic information processing within and. Unintended thought, 212.Hovland, C. I., Janis, I. L., & Kelley, H. H. (1953). Communication and persuasion; psychological studies of opinion change.Murdock Jr, B. B. (1962). The serial position effect of free recall. Journal of experimental psychology, 64(5), 482.Petty, R. E., & Cacioppo, J. T. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. In Communication and persuasion (pp. 1-24). Springer New York.Scheufele, D. A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of communication, 57(1), 9-20.Skinner, B. F. (1958). Reinforcement today. American Psychologist, 13(3), 94.Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories: Studies in social psychology. CUP Archive.Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive psychology, 5(2), 207-232.Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9(2p2), 1.

Dove’s Legacy campaign

Personal care brand Dove has kick- started a campaign to promote beauty between mothers and daughters. After their award- winning “Real Beauty Sketches” project, the Dove Legacy campaign is the next creation to boost self- confidence in women. The short film begins by asking a small group of mothers how they felt about their body. The responses were overwhelmingly negative, ranging from “my eyes are wonky” to “I have very big legs.” This is relatively expected, as recent statistics have shown that 61% of women in the US, 87% in China and a staggering 96% in the UK feel anxious about the way they look. To see how this has impacted their children, the filmmakers then continue to ask their daughters the same question. Unfortunately, yet unsurprisingly, the mothers and daughters’ answers were close to identical. When the mothers were asked to read out their child’s list, comments such as “we both don’t like our nose” and “she doesn’t like her arms either” quickly made the mothers realise “she really picks up on a lot of my ways.” It becomes evident throughout the film clip that the complaints mothers have about their own bodies, will soon be applied to their young daughters too. The short film clip and campaign have raised an awareness for mothers to boost their daughters’ confidence, by first displaying their own self- confidence.You can view the campaign here: The success of the campaign is largely due to the underlying message Dove has cleverly devised. Modelling is a psychological phenomenon referring to the imitation of an individual, in this instance the mother, by another individual, the daughter. Resultantly new behaviours and skills can be developed. The relationship between mothers and daughters is a highly researched area of psychology, due to the natural maternal instinct present since birth. A recent study by Diedrichs et at (2016) investigated the effect of a mothers’ body image on their daughters self- reflected body image. It was found that mothers who participated in the Dove Self Esteem Project Website for Parents reported significantly higher self- esteem post exposure. Consequently, the daughters of these mothers also had a correlated higher self- esteem and reduced negative affect after a six week follow up. This study evidences a clear link between how a mother views their body image, and how it significantly impacts the body image of their daughter. The Dove campaign, along with critical research, highlights the importance of a positive female role model on a young girls’ self- esteem. Such views on body image are passed down generations and can continue throughout an individual’s lifetime. The take home message from the Legacy campaign encourages mothers and female role models to display self- confidence, to inspire young girls to do the same. References: Diedrichs, P. C., Atkinson, M. J., Garbett, K. M., Williamson, H., Halliwell, E., Rumsey, N., & Barlow, F. K. (2016). Randomized controlled trial of an online mother- daughter body image and well- being intervention. Health Psychology: Official Journal Of The Division Of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(9), 996-1006.

Media Coverage of Suicides and Werther Effect

It is shameful to say, but my home country South Korea’s suicide rate remains highest among members of the OECD and this is also apparent among students. In fact, suicide is the leading cause of death among South Korean teenagers. Statistics Korea (2014) reported that suicide was the number one cause of death among people aged 10 to 39. As teenagers are emotionally unstable and are susceptible to other people’s behavior, they are largely influenced by media coverage of suicides. The influence maximizes when the report is about a celebrity’s suicide. Consequence could be as serious as more teenagers committing suicides, following what they’ve seen in the media. Such increase of copycat suicides after a “widely publicized suicide” is called Werther effect.  Monthly total number of suicides (South Korea 2005-2008). Arrows indicate points of celebrity suicides. There were seven cases of celebrity suicides from 2005 to 2008 in South Korea, and each one of them produced numerous follow-up reports on all kinds of media including newspaper and television. An analysis of subsequent suicides revealed that they definitely induced copycat suicides (Jang, Sung, Park, & Jeon, 2016). There was a great increase in the number of suicides, especially among people of the same gender, and many of them used the same method. The Korean Association for Suicide Prevention suggested a “recommendation for media reports on suicide” in 2004, yet substantial media coverage has still been reported. Stronger regulations are needed for better media reporting of suicides. For instance, specific depiction of the suicide method should be restricted. In addition to stricter measures to media coverage, there has to be an effective system within the society ready to cope with potential copycat suicides.References Jang, S. A., Sung, J. M., Park, J. Y., & Jeon, W. T. (2016). Copycat suicide induced by entertainment celebrity suicides in South Korea. Psychiatry investigation, 13(1), 74-81. Ji, N. J., Lee, W. Y., Noh, M. S., & Yip, P. S. (2014). The impact of indiscriminate media coverage of a celebrity suicide on a society with a high suicide rate: epidemiological findings on copycat suicides from South Korea. Journal of affective disorders, 156, 56-61. Korea, S. (2014). Cause of death statistics of Korea. Stack, S. (1987). Celebrities and suicide: A taxonomy and analysis, 1948-1983. American sociological review, 401-412.

Monthly total number of suicides (South Korea 2005-2008). Arrows indicate points of celebrity suicides. There were seven cases of celebrity suicides from 2005 to 2008 in South Korea, and each one of them produced numerous follow-up reports on all kinds of media including newspaper and television. An analysis of subsequent suicides revealed that they definitely induced copycat suicides (Jang, Sung, Park, & Jeon, 2016). There was a great increase in the number of suicides, especially among people of the same gender, and many of them used the same method. The Korean Association for Suicide Prevention suggested a “recommendation for media reports on suicide” in 2004, yet substantial media coverage has still been reported. Stronger regulations are needed for better media reporting of suicides. For instance, specific depiction of the suicide method should be restricted. In addition to stricter measures to media coverage, there has to be an effective system within the society ready to cope with potential copycat suicides.References Jang, S. A., Sung, J. M., Park, J. Y., & Jeon, W. T. (2016). Copycat suicide induced by entertainment celebrity suicides in South Korea. Psychiatry investigation, 13(1), 74-81. Ji, N. J., Lee, W. Y., Noh, M. S., & Yip, P. S. (2014). The impact of indiscriminate media coverage of a celebrity suicide on a society with a high suicide rate: epidemiological findings on copycat suicides from South Korea. Journal of affective disorders, 156, 56-61. Korea, S. (2014). Cause of death statistics of Korea. Stack, S. (1987). Celebrities and suicide: A taxonomy and analysis, 1948-1983. American sociological review, 401-412.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- …

- 64

- Next Page »