Guest Blog by Ron Holloway

Ron is the owner of Arrow Coaching, LLC. He pairs his studies and research with the experience with becoming blind and cognitively impaired to an invaluable thought leader in the government and beyond. Connect with him on LinkedIn.

Lessons From Boxing

Mike Tyson once said, “every fighter has a plan until he gets punched in the mouth.”

I want to add that the amateur might forget the plan and get emotional whereas the professional fighter takes it, feels the blow and gets back to the plan. The shock makes the amateur panic and helps the professional focus.

We can say the same about life and emergency management when one encounters their metaphorical punch in the face with either an untrained mind or a trained mind.

What happens after that hit is the result of everything that went into preparing for it.

As, Sun Tzu said, “The battle is won before the fighting.” Or what I learned as a soldier, we don’t rise to the occasion; we default to our level of training.

As an anti-fragility coach and consultant, I prepare individuals and organizations to be like that professional fighter.

In particular, I develop leaders for that moment when everyone turns to them with fear in their eye’s and say, “What do we do?”

Ron’s 4-Part System

My system draws on philosophy, psychology, physiology, and spirituality.

Like boxing there are principles, such as keeping your hands up and throwing combinations. There are also techniques to drill into your muscle memory until they become automatic.

How it Applies to You

But you might be saying, I’m not a boxer what do I need this for? Well, there are benefits in the real world that will come with being a champion.

An example we can draw from is the initial public response to Covid-19. Some people rushed out and bought a ton of toilet paper for a condition that affects the respiratory system not the gastro-intestinal system.

Others asked themselves the classic stoic question of “how do I turn this to my advantage?” and those people invested in Zoom and saw their investment quadruple over the next few months.

Amazon, Circuit City, and Best Buy

This doesn’t only apply on the individual level. A great example is found in the consumer electronics market.

When Amazon entered that ecosystem, Circuit City went into denial and didn’t adapt.

Best Buy adapted and diversified by finding other areas to improve, the Geek Squad, the sale of high-end home appliances and home theatre systems, and training the sales people to develop subject matter expertise in products and to sell not just to husbands but also their wives. These are what make Best Buy the last man standing.

In the Darwinian sense Best Buy is the fittest and Circuit City is extinct. Now this lesson is part of Best Buy’s corporate story and culture and as is often written, culture trumps strategy any day.

Post Pandemic

As we emerge out of the global pandemic, we need to do an after action review. We need to ask ourselves as individuals, organizations, and a country if next time disruption occurs will we waste money and precious time on a lifetime supply of Charmin, or are we going to get the contract for those social distancing stickers in front of every register in every store in the country?

Want to enhance your knowledge about emotions, skills in reading emotions in others, and your own emotion regulation competence? Check out our online courses here!

The post Opportunity Favors the Prepared first appeared on Humintell.

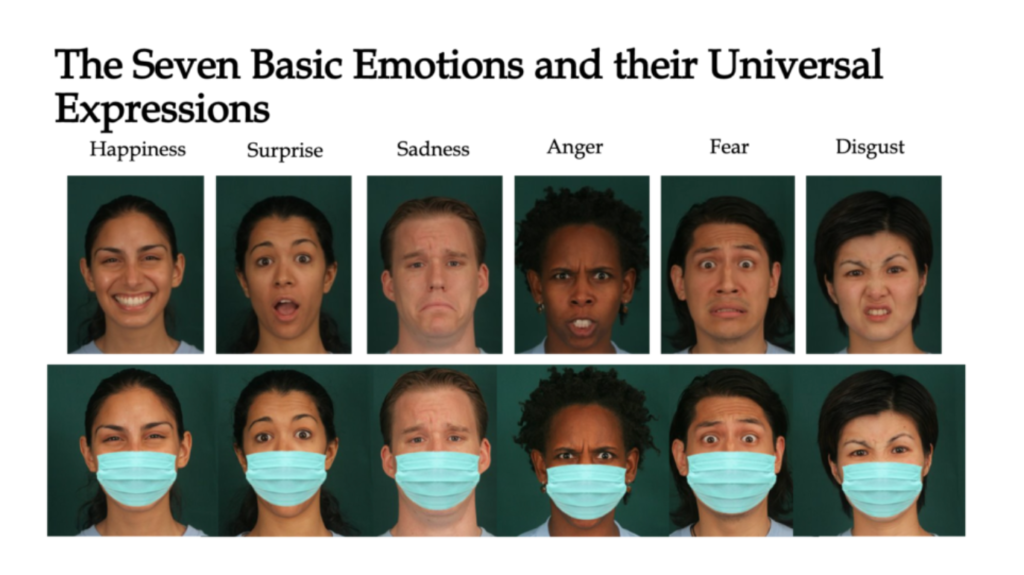

Research has shown that infants as young as 27 weeks old begin to recognize facial expressions of emotion. In addition, a series of studies have shown that babies between the ages of 5 to 7 months recognize facial expressions of happiness, sadness, fear and surprise.

Research has shown that infants as young as 27 weeks old begin to recognize facial expressions of emotion. In addition, a series of studies have shown that babies between the ages of 5 to 7 months recognize facial expressions of happiness, sadness, fear and surprise. While essential emotion processing is evident in infants, early childhood is considered a critical period for the development of understanding emotions and emotion processing.

While essential emotion processing is evident in infants, early childhood is considered a critical period for the development of understanding emotions and emotion processing.