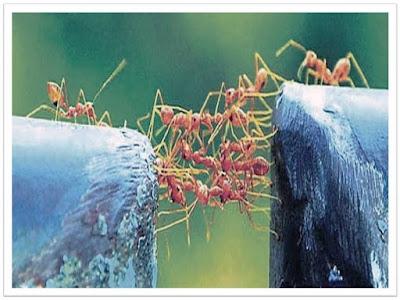

Where does our tendency to cooperate come from? Is it natural for us to cooperate or is it the result of social learning? It’s tempting to think that we’re born as non-cooperative beasts that need to be tamed via education and other forms of cultural learning. The whole idea of ‘human civilization’ revolves around the assumption that humans have somehow risen above animals because they can cooperate, have morals and be kind to one another.But even a casual look at nature will convince you that cooperation is not exclusive to humans. Chimpanzees cooperate, bees cooperate, wolves cooperate, birds cooperate, ants cooperate… the list goes on and on. There are myriad species in nature that cooperate with their conspecifics.This leads one to think that cooperation in humans must also have its roots in natural selection- that cooperation may not be entirely the result of cultural conditioning but something that we’re born with.Evolution of cooperationCooperation is usually a good thing for species to possess because it enables them to do things efficiently. What an individual cannot do by itself a group can. If you’ve ever observed ants carefully you must’ve seen how they share the load of a particularly heavy grain that a single ant couldn’t possibly carry. Tiny yet fascinating! Ants building a bridge out of themselves to help others cross over.In us humans too, cooperation is something that should be favoured by natural selection because it’s beneficial. By cooperating humans can better their chances of survival and reproduction. Individuals who cooperate are more likely to pass on their genes.But there’s a flipside to the story. Individuals who cheat and don’t cooperate are also more likely to be reproductively successful. Individuals who receive all the benefits a group provides but don’t contribute anything have an evolutionary advantage over those who do cooperate. Such individuals lay their hands on more resources and hardly incur any costs. Since the availability of resources can be correlated with reproductive success, over evolutionary time, the number of cheaters in a population must increase.The only way in which the evolution of cooperation can happen is if humans have the psychological mechanisms to detect, avoid and punish cheaters. If cooperators can detect cheaters and interact with only like-minded cooperators, cooperation and reciprocal altruism can gain a toehold and evolve over time.Psychological mechanisms favouring cooperationIf you pause to think about all psychological mechanisms that we possess to detect and avoid cheaters, you’ll soon realize that a rather great part of our psyche is devoted to these ends.We have the ability to recognize many different individuals, not just by their names but also by the way they talk, walk and the sound of their voice. Identifying many different individuals helps us identify who is cooperative and who is non-cooperative.No sooner do new people meet than they form quick judgments about each other, mostly about how cooperative or non-cooperative they’re going to be.“She’s nice and very helping.” “He has a kind heart.”“She’s selfish.”“He’s not the type who shares his stuff.”Similarly, we have the ability to remember our past interactions with different people. If someone deceives us, we tend to remember this event vividly and vow never to trust that person again or demand an apology. Those who help us we put them in our good books.Imagine what chaos would ensue if you were unable to keep track of those who’ve been non-cooperative toward you? They’d continue to take advantage of you causing you tremendous loss.Interestingly, we not only keep track of those who’re good or bad to us but also how much they’re good or bad to us. This is where reciprocal altruism kicks in. If a person does x amount of favour upon us, we feel obliged to return the favour in x amount. If a person does a huge favour upon us, we feel obliged to repay in a big way (the common expression, “How can I repay you?”). If person does a not-so-big favour for us, we return them a not-so-big favour.Add to all this our capacity to understand each other’s needs, convey our own and feel guilty or bad if we’re disappointed or if we disappoint others. All these things are in-built in us to promote cooperation.It all boils down to cost v/s benefitsJust because we’re evolved to cooperate does not mean non-cooperation does not happen. Given the right circumstances, when the benefit of not cooperating is greater than the benefit of cooperating, non-cooperation can and does happen.The evolution of cooperation in humans only suggests that there is a general tendency in the human psyche to cooperate with others for mutual benefit. Generally, we feel good when cooperation that is beneficial to us happens and feel bad when non-cooperation that is harmful for us happens.

Tiny yet fascinating! Ants building a bridge out of themselves to help others cross over.In us humans too, cooperation is something that should be favoured by natural selection because it’s beneficial. By cooperating humans can better their chances of survival and reproduction. Individuals who cooperate are more likely to pass on their genes.But there’s a flipside to the story. Individuals who cheat and don’t cooperate are also more likely to be reproductively successful. Individuals who receive all the benefits a group provides but don’t contribute anything have an evolutionary advantage over those who do cooperate. Such individuals lay their hands on more resources and hardly incur any costs. Since the availability of resources can be correlated with reproductive success, over evolutionary time, the number of cheaters in a population must increase.The only way in which the evolution of cooperation can happen is if humans have the psychological mechanisms to detect, avoid and punish cheaters. If cooperators can detect cheaters and interact with only like-minded cooperators, cooperation and reciprocal altruism can gain a toehold and evolve over time.Psychological mechanisms favouring cooperationIf you pause to think about all psychological mechanisms that we possess to detect and avoid cheaters, you’ll soon realize that a rather great part of our psyche is devoted to these ends.We have the ability to recognize many different individuals, not just by their names but also by the way they talk, walk and the sound of their voice. Identifying many different individuals helps us identify who is cooperative and who is non-cooperative.No sooner do new people meet than they form quick judgments about each other, mostly about how cooperative or non-cooperative they’re going to be.“She’s nice and very helping.” “He has a kind heart.”“She’s selfish.”“He’s not the type who shares his stuff.”Similarly, we have the ability to remember our past interactions with different people. If someone deceives us, we tend to remember this event vividly and vow never to trust that person again or demand an apology. Those who help us we put them in our good books.Imagine what chaos would ensue if you were unable to keep track of those who’ve been non-cooperative toward you? They’d continue to take advantage of you causing you tremendous loss.Interestingly, we not only keep track of those who’re good or bad to us but also how much they’re good or bad to us. This is where reciprocal altruism kicks in. If a person does x amount of favour upon us, we feel obliged to return the favour in x amount. If a person does a huge favour upon us, we feel obliged to repay in a big way (the common expression, “How can I repay you?”). If person does a not-so-big favour for us, we return them a not-so-big favour.Add to all this our capacity to understand each other’s needs, convey our own and feel guilty or bad if we’re disappointed or if we disappoint others. All these things are in-built in us to promote cooperation.It all boils down to cost v/s benefitsJust because we’re evolved to cooperate does not mean non-cooperation does not happen. Given the right circumstances, when the benefit of not cooperating is greater than the benefit of cooperating, non-cooperation can and does happen.The evolution of cooperation in humans only suggests that there is a general tendency in the human psyche to cooperate with others for mutual benefit. Generally, we feel good when cooperation that is beneficial to us happens and feel bad when non-cooperation that is harmful for us happens.

Reciprocal altruism: Helping and forming bonds with nonrelatives

It was the birthday of a co-worker of Monica’s. It had been four years now them working together. Previously, they just used to greet each other on their respective birthdays. But this year Monica’s friend gave her a gift on her birthday. Monica felt compelled to the same for her friend, even though she’d never done it before.When someone does a favor for us, why do we feel tempted to return it?Why are we likely to help those who’ve helped us before?Why do we tend to buy gifts for those who do the same for us?Reciprocal altruismOne should expect altruistic acts from one’s immediate family- one’s closest genetic relatives. This is because by helping each other survive and reproduce, a family is essentially helping its shared genes to successfully pass on to the next generation.But what explains altruism outside of the family?Why do people form close bonds with those who’re not related to them?It’s all due to a psychological phenomenon known as reciprocal altruism. In simple words, reciprocal altruism is nothing but mutual benefit. We form bonds with people and help them so that we may get helped in return. Friendships simply can’t exist without the prospect of mutual benefit. Origins of reciprocal altruismDuring most of our evolutionary history, hunting was the main activity for procuring food. But success from hunting was unpredictable and erratic. One week a hunter would obtain more meat than required and another week he’d acquire nothing at all. Add to this the fact that meat can’t be stored for long and is easily spoiled. Our hunter ancestors therefore could only survive if they somehow ensured a continual supply of food. This generated selection pressure for reciprocal altruism, meaning that those who had mutual altruistic tendencies were more likely to survive and out-reproduce those who did not have such tendencies. Those who were helped, helped others in the future. Therefore, altruistic tendencies are widespread amongst today’s humans.Reciprocal altruism is found in the animal kingdom too. Chimpanzees, our closest cousins, form alliances to boost their chances of survival and reproduction. A dominant male-male alliance in chimps is likely to out-reproduce other males.Vampire bats that suck cattle blood at night don’t always succeed. It has been observed that these bats provide regurgitated blood to their ‘friends’ when they’re in dire need. These ‘friends’ are bats who had provided them with blood in the past! They form close associations with each other even though they’re unrelated.Shadow of the futureReciprocal altruism is likely to occur when there’s a large shadow of the future. If the other person thinks that they’ll be interacting with you frequently in the extended future, then they have a strong incentive to be altruistic towards you. They expect you’ll be altruistic towards them in the future too.On the other hand, if the other person thinks that they won’t be interacting with you for long (i.e. a small shadow of the future), then there seems to be no point in being altruistic. This is one reason why most friendships in schools and colleges happen at the beginning of the academic year and not when the course is nearing its end.At the beginning, students seek other students who might benefit them during the course. There’s simply no point in making friends when you’re hardly going to interact in the future. If it looks like a friend is going to be altruistic towards you beyond college, then you’re likely to form a lifelong bond with that friend. If a friend has helped you a lot in the past and so have you, then you’re likely to form a lifelong friendship with them because you’ve both already demonstrated your respective commitment to reciprocal altruism.When there’s no future to look forward to, chances of reciprocal altruism are less. It’s all about mutual benefit.

Origins of reciprocal altruismDuring most of our evolutionary history, hunting was the main activity for procuring food. But success from hunting was unpredictable and erratic. One week a hunter would obtain more meat than required and another week he’d acquire nothing at all. Add to this the fact that meat can’t be stored for long and is easily spoiled. Our hunter ancestors therefore could only survive if they somehow ensured a continual supply of food. This generated selection pressure for reciprocal altruism, meaning that those who had mutual altruistic tendencies were more likely to survive and out-reproduce those who did not have such tendencies. Those who were helped, helped others in the future. Therefore, altruistic tendencies are widespread amongst today’s humans.Reciprocal altruism is found in the animal kingdom too. Chimpanzees, our closest cousins, form alliances to boost their chances of survival and reproduction. A dominant male-male alliance in chimps is likely to out-reproduce other males.Vampire bats that suck cattle blood at night don’t always succeed. It has been observed that these bats provide regurgitated blood to their ‘friends’ when they’re in dire need. These ‘friends’ are bats who had provided them with blood in the past! They form close associations with each other even though they’re unrelated.Shadow of the futureReciprocal altruism is likely to occur when there’s a large shadow of the future. If the other person thinks that they’ll be interacting with you frequently in the extended future, then they have a strong incentive to be altruistic towards you. They expect you’ll be altruistic towards them in the future too.On the other hand, if the other person thinks that they won’t be interacting with you for long (i.e. a small shadow of the future), then there seems to be no point in being altruistic. This is one reason why most friendships in schools and colleges happen at the beginning of the academic year and not when the course is nearing its end.At the beginning, students seek other students who might benefit them during the course. There’s simply no point in making friends when you’re hardly going to interact in the future. If it looks like a friend is going to be altruistic towards you beyond college, then you’re likely to form a lifelong bond with that friend. If a friend has helped you a lot in the past and so have you, then you’re likely to form a lifelong friendship with them because you’ve both already demonstrated your respective commitment to reciprocal altruism.When there’s no future to look forward to, chances of reciprocal altruism are less. It’s all about mutual benefit.

Why rural families tend to have more children

Numerous factors have come together to make the evolution of family possible in us homo sapiens. Typically, families evolve in the animal kingdom when individuals can increase their odds of reproductive success by staying close to, and helping, their genetic relatives.A family is just a bunch of people with shared genes who’re trying to ensure the replicative success of these genes. A family is a behavioral strategy evolved in genes to ensure their transfer to the next generation, using individuals as vehicles.Each individual within a family has something to gain by being in the family- otherwise the family would disintegrate. Although this gain is primarily reproductive success, there are also other gains such protection, access to resources, bonding, well-being, etc.Measuring reproductive success of a familyGenerally, the more offspring a family produces the greater will be its reproductive success- just like a manufacturing company is likely to gain more profits if it produces more units. The more copies a set of genes makes of itself the better.But things are rarely that simple. Often, there are other factors to consider. Making copies is not enough. You got to make copies that will successfully be able to make their own copies in the future. Now that type of success is dependent on a number of variables- the primary ones being ‘risk of disease’ and ‘availability of resources’.We have subconscious psychological mechanisms designed to operate on these variables. More often than not, our psychological mechanisms seem irrational in today’s context because they were evolved to work in Stone Age.As you will see, the same subconscious strategy can turn out to be rational (vis-a-vis reproductive success) in one context and irrational in another.Let’s see how ‘risk of disease’ and ‘availability of resources’ influence the number of offspring a family has…Risk of diseaseFor most of human evolutionary history, people lived as hunter gatherers. Generally, men hunted animals and women foraged for fruit and vegetables. Societies were made up of small scattered bands of people who lived and moved together.Their diet was protein-rich and most deaths were due to accident, predation and inter-group warfare. Risk of diseases, especially contagious diseases, was low. The chances of offspring dying due to disease were low and so families produced a few children (three or four) who were likely survive.Large families appeared on the scene only when agricultural revolution happened about ten thousand years ago. In areas that were most fertile, typically river valleys, large and concentrated communities emerged living on a carbohydrate-rich diet. The consequence of this was a greater risk of disease, especially virulent diseases. So, as a defense strategy, families typically produced a large number of children in these times. Even if 15 out of 20 children died due to disease, 5 lived to continue their genetic lines. This behavior is explained by the psychological phenomenon known as loss aversion. It basically means that we’re driven to avoid losses as much as we can. Having a greater number of children allowed our farmer ancestors to increase the probability of their reproductive success.This is an example of how a subconscious biological strategy can produce reproductively desired results.Today, thanks to the advances in medicine and hygiene, the number of children a family produces is low (two or three). Parents know, consciously or unconsciously, that the survival chances of their offspring are pretty high. No need to go overboard.But what about those areas that lack proper healthcare even today? Say, for example, rural areas of developing countries?In these areas, since risk of disease is essentially high, families opt to bear a greater number of children. Availability of resourcesAll other factors being constant, the greater the resources a family has, the greater should be the number of children that they bear. Why? Because the more resources a family has, the more it can distribute these to its heirs. This is partly the reason why kings and despots back in the day had numerous children. They could provide equally for all of them if they wanted for they collected most of the wealth and resources of the land. The chances of survival and reproduction of an offspring are directly dependent upon the amount of resources parents can invest in it.Of course, you should expect the opposite when it comes to families with fewer resources. The rational thing for them to do is to bear few children amongst whom they can distribute their limited resources.So, in rural areas, where people in general tend to be poorer, you should expect families with minimal children. But this is rarely observed. In fact the opposite is true. Rural families, even if they have fewer resources, tend to have more children.A consequence of the psychological phenomenon of loss aversion is that when faced with a potential loss, we’re likely to take irrational risks to compensate for the impending loss.So people in rural areas are like, subconsciously, “Screw it! Let’s have as many kids as we can”. It’s essentially a defense in the face of a loss- a reproductive loss that is responded to by seeking irrational reproductive gain.This is an example of a subconscious psychological strategy turning out to be irrational.

Availability of resourcesAll other factors being constant, the greater the resources a family has, the greater should be the number of children that they bear. Why? Because the more resources a family has, the more it can distribute these to its heirs. This is partly the reason why kings and despots back in the day had numerous children. They could provide equally for all of them if they wanted for they collected most of the wealth and resources of the land. The chances of survival and reproduction of an offspring are directly dependent upon the amount of resources parents can invest in it.Of course, you should expect the opposite when it comes to families with fewer resources. The rational thing for them to do is to bear few children amongst whom they can distribute their limited resources.So, in rural areas, where people in general tend to be poorer, you should expect families with minimal children. But this is rarely observed. In fact the opposite is true. Rural families, even if they have fewer resources, tend to have more children.A consequence of the psychological phenomenon of loss aversion is that when faced with a potential loss, we’re likely to take irrational risks to compensate for the impending loss.So people in rural areas are like, subconsciously, “Screw it! Let’s have as many kids as we can”. It’s essentially a defense in the face of a loss- a reproductive loss that is responded to by seeking irrational reproductive gain.This is an example of a subconscious psychological strategy turning out to be irrational.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- …

- 24

- Next Page »