By now, we’ve all seen them in one way or another. Whether it be in person (Halloween is approaching…), on our social media newsfeeds or in the media. Newspaper headlines read ‘Killer clown craze: 12 of the creepiest UK sightings’ (The Telegraph, 17th Oct), ‘Killer clown with machete threatens two girls in Suffolk’ (The Telegraph, 16th Oct), ‘Childline flooded with calls about killer clown craze’ (Daily Mail, 13th Oct). With the number of these ‘killer clowns’ growing exponentially, you’ve got to ask the question of what took this from a Halloween outfit to a craze confining communities to their homes.It may not come as a surprise that research has shown the media is strikingly successful in telling its audience what to think about. The more the media reports something, the more available that information is to us and the more frequently we think about it. The agenda setting theory, first proposed in 1922, outlines this effect. It is not surprising then, that killer clowns have become the topic of conversation with them consecutively filling newspaper headlines and their masks filling every scroll down social media. Could it be that this high exposure is what has caused the ‘craze’? Could it be that the volume of others putting on a mask is what is encouraging so many more to do the same?

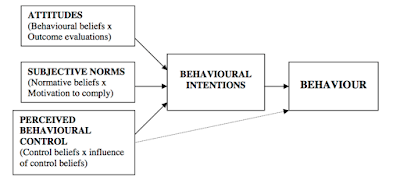

By now, we’ve all seen them in one way or another. Whether it be in person (Halloween is approaching…), on our social media newsfeeds or in the media. Newspaper headlines read ‘Killer clown craze: 12 of the creepiest UK sightings’ (The Telegraph, 17th Oct), ‘Killer clown with machete threatens two girls in Suffolk’ (The Telegraph, 16th Oct), ‘Childline flooded with calls about killer clown craze’ (Daily Mail, 13th Oct). With the number of these ‘killer clowns’ growing exponentially, you’ve got to ask the question of what took this from a Halloween outfit to a craze confining communities to their homes.It may not come as a surprise that research has shown the media is strikingly successful in telling its audience what to think about. The more the media reports something, the more available that information is to us and the more frequently we think about it. The agenda setting theory, first proposed in 1922, outlines this effect. It is not surprising then, that killer clowns have become the topic of conversation with them consecutively filling newspaper headlines and their masks filling every scroll down social media. Could it be that this high exposure is what has caused the ‘craze’? Could it be that the volume of others putting on a mask is what is encouraging so many more to do the same?  Figure One: The Theory of Planned BehaviourThe theory of planned behaviour suggests there are three components that lead to an intention to perform a certain behaviour (see figure one). Perceived behavioural control is simply the belief that you can control your behaviour. Perhaps the consequence of going out and scaring your community is too high; a risk of arrest, for example. But, thanks to the medias mass publications of clowns filling the streets, their perceived behavioural control is reassessed. An individual’s belief that they can to perform this behaviour grows, under the cover of a mask. Suddenly, a behaviour that seemed out of reach is not so anymore. This of course, ties in with social norms. Whilst it may have been considered unacceptable to go and scare your local community before, suddenly a lot more people doing it and it rapidly becomes a much more normative, and therefore an accepted behaviour to perform. Of course, it is the media that ensures we are aware of the growing number of clowns in our streets. The attitude towards the behaviour, in this example at least, is likely to build from the other components. The majority of us are probably horrified by these killer clowns, however, there are clearly individuals who have a more positive attitude to the craze. Or perhaps a more positive attitude of the behaviour has been formed as a result of the high exposure; it could be considered humourous rather than horrifying. According to the theory of planned behaviour, the combination of these three components lead to an intent to perform a behaviour. Although hard to get inside the head of a killer clown, you can see how putting on a mask, wig and wandering the local streets can suddenly be perceived as more acceptable; a belief that we possibly owe to media sources for sharing. This media exposure should boldly take its place in the diagram of the theory of planned behaviour, feeding into the three components that influence behaviour intentions (see figure two).

Figure One: The Theory of Planned BehaviourThe theory of planned behaviour suggests there are three components that lead to an intention to perform a certain behaviour (see figure one). Perceived behavioural control is simply the belief that you can control your behaviour. Perhaps the consequence of going out and scaring your community is too high; a risk of arrest, for example. But, thanks to the medias mass publications of clowns filling the streets, their perceived behavioural control is reassessed. An individual’s belief that they can to perform this behaviour grows, under the cover of a mask. Suddenly, a behaviour that seemed out of reach is not so anymore. This of course, ties in with social norms. Whilst it may have been considered unacceptable to go and scare your local community before, suddenly a lot more people doing it and it rapidly becomes a much more normative, and therefore an accepted behaviour to perform. Of course, it is the media that ensures we are aware of the growing number of clowns in our streets. The attitude towards the behaviour, in this example at least, is likely to build from the other components. The majority of us are probably horrified by these killer clowns, however, there are clearly individuals who have a more positive attitude to the craze. Or perhaps a more positive attitude of the behaviour has been formed as a result of the high exposure; it could be considered humourous rather than horrifying. According to the theory of planned behaviour, the combination of these three components lead to an intent to perform a behaviour. Although hard to get inside the head of a killer clown, you can see how putting on a mask, wig and wandering the local streets can suddenly be perceived as more acceptable; a belief that we possibly owe to media sources for sharing. This media exposure should boldly take its place in the diagram of the theory of planned behaviour, feeding into the three components that influence behaviour intentions (see figure two).  Figure Two: Addition of Agenda Setting to Theory of Planned BehaviourThe role of the media treads a very fine line. The damaging effects of them sharing the latest craze can clearly be seen, essentially taking what could have been a few separate instances to the ‘killer clown craze’. But, how long would it take for us to begin to resent the media should they stop sharing the latest horrors? Would we not be outraged if we came face-to-face with a killer clown only to find we could have been warned to stay in our homes, if the media had published the latest instances it had been informed of? Regardless, this latest craze illustrates the strength of agenda setting theory, and the power the media has over us and our behaviours.ReferencesFrancis, J. J., Eccles, M. P., Johnston, M., Walker, A., Grimshaw, J., Foy, R., Kaner, E. F. S., Smith, L., & Bonetti, D. (2004). Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour. A manual for health services researchers, 2010, 2-12. Rogers, E. M., Dearing, J. W., & Bregman, D. (1993). The anatomy of agenda‐setting research. Journal of communication, 43(2), 68-84.

Figure Two: Addition of Agenda Setting to Theory of Planned BehaviourThe role of the media treads a very fine line. The damaging effects of them sharing the latest craze can clearly be seen, essentially taking what could have been a few separate instances to the ‘killer clown craze’. But, how long would it take for us to begin to resent the media should they stop sharing the latest horrors? Would we not be outraged if we came face-to-face with a killer clown only to find we could have been warned to stay in our homes, if the media had published the latest instances it had been informed of? Regardless, this latest craze illustrates the strength of agenda setting theory, and the power the media has over us and our behaviours.ReferencesFrancis, J. J., Eccles, M. P., Johnston, M., Walker, A., Grimshaw, J., Foy, R., Kaner, E. F. S., Smith, L., & Bonetti, D. (2004). Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour. A manual for health services researchers, 2010, 2-12. Rogers, E. M., Dearing, J. W., & Bregman, D. (1993). The anatomy of agenda‐setting research. Journal of communication, 43(2), 68-84.

Propaganda for Change

“It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.” Jiddu Krishnamurti On August 28th 1963, Martin Luther King took centre stage in Washington D.C and delivered one of the finest speeches in recorded history to 250,000 people- 250,000 people willing to listen to the voice of a minority, a voice that challenged the archaic racial view embedded in the masses. One year later President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. The opinion-deviant majority alter-cast or minority influence principle (Moscovici, Lage & Naffrechoux, 1969) accounts for some of history’s defining moments and proposes that if the minority is consistent, confident and committed in their judgement they become effective communicators (Moscovici, 1976). To give a more contemporary example, take Russell Brand- Dave Grohl and Jesus Christ’s cockney, comedian lovechild recently appeared on Newsnight and in the space of 10 minutes delivered one of the most well-articulated, slightly verbose accounts of bullshit ever presented on national television. However, the critical factors of consistency, confidence and commitment in his own argument managed to transform the generic largely politically unconcerned Facebook statuses of the British youth from the tedium of hangover updates and circling reviews to those of fierce aspiring revolutionaries. The point is whether you’re a hippy, conservative, liberal, homosexual, terrorist, freedom fighter, average Joe, anarchist, Pope, white, black, clinically insane, partisan, Christian, Muslim, pagan, masochist, peasant, president, romantic, ladies, gentleman it does not matter, if you have enough belief in an idea you can change the world.Moscovici (1976) demonstrated the effect of minority influence in one of the classic psychological studies. In the control condition a group of up to 6 naïve participants viewed a series of slides depicting various shades of blue. After being shown a slide participants were in turn required to say out loud the colour they had just seen before moving on to the next one. Under such conditions near much everyone identified the slides as being blue meaning the colour of the slide was deemed relatively unambiguous. In two experimental conditions a numerical minority (2/6) of the group were confederates of the experimenter and gave pre-agreed responses (Martin & Hewstone, 2012). Similarly to the control condition when presented with the series of blue slides participants were in turn asked to say aloud the colour they perceived. Confederates responded first and identified the depicted colour as ‘green’, an interpretation which clearly differed to that of the naïve participants. In the ‘consistent-minority condition’ confederates answered with the incorrect ‘green’ response on every trial and those in the ‘inconsistent-minority condition’ deliberately responded incorrectly on 2/3 of all trials.

On August 28th 1963, Martin Luther King took centre stage in Washington D.C and delivered one of the finest speeches in recorded history to 250,000 people- 250,000 people willing to listen to the voice of a minority, a voice that challenged the archaic racial view embedded in the masses. One year later President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law. The opinion-deviant majority alter-cast or minority influence principle (Moscovici, Lage & Naffrechoux, 1969) accounts for some of history’s defining moments and proposes that if the minority is consistent, confident and committed in their judgement they become effective communicators (Moscovici, 1976). To give a more contemporary example, take Russell Brand- Dave Grohl and Jesus Christ’s cockney, comedian lovechild recently appeared on Newsnight and in the space of 10 minutes delivered one of the most well-articulated, slightly verbose accounts of bullshit ever presented on national television. However, the critical factors of consistency, confidence and commitment in his own argument managed to transform the generic largely politically unconcerned Facebook statuses of the British youth from the tedium of hangover updates and circling reviews to those of fierce aspiring revolutionaries. The point is whether you’re a hippy, conservative, liberal, homosexual, terrorist, freedom fighter, average Joe, anarchist, Pope, white, black, clinically insane, partisan, Christian, Muslim, pagan, masochist, peasant, president, romantic, ladies, gentleman it does not matter, if you have enough belief in an idea you can change the world.Moscovici (1976) demonstrated the effect of minority influence in one of the classic psychological studies. In the control condition a group of up to 6 naïve participants viewed a series of slides depicting various shades of blue. After being shown a slide participants were in turn required to say out loud the colour they had just seen before moving on to the next one. Under such conditions near much everyone identified the slides as being blue meaning the colour of the slide was deemed relatively unambiguous. In two experimental conditions a numerical minority (2/6) of the group were confederates of the experimenter and gave pre-agreed responses (Martin & Hewstone, 2012). Similarly to the control condition when presented with the series of blue slides participants were in turn asked to say aloud the colour they perceived. Confederates responded first and identified the depicted colour as ‘green’, an interpretation which clearly differed to that of the naïve participants. In the ‘consistent-minority condition’ confederates answered with the incorrect ‘green’ response on every trial and those in the ‘inconsistent-minority condition’ deliberately responded incorrectly on 2/3 of all trials.  Figure 1: a bar chart demonstrating the percentage of green responses by naïve participants in each condition.Results reported that the presence of a minority that consistently provided unusual responses influenced the judgments made by naive participants in that 32% of the consistent-minority condition conformed to the confederate response at least once and as can be deduced from figure 1 18% of all responses in this condition were green . However, the inconsistent minority had virtually no influence over the majority whatsoever, which supports Moscovici et al.’s (1969) claim that consistency is one the keys to minority influence. In summary either we need to confiscate Russell Brand’s thesaurus or wait until he inevitably begins to make contradictory statements before we switch off when he says something he didn’t intend to be a joke- power to the people. Rory MacLeodReferences Martin, R., & Hewstone, M. (2012). Minority influence: Revisiting Moscovici’s blue-green afterimage studies. In J. R. Smith, & S. Alexander-Haslam (Eds.), Social psychology: Revisiting the classic studies (pp. 91-106). London, England: Sage Publications. Moscovici, S., Lage, E., & Naffrechoux, M. (1969). Influence of a consistent minority on the responses of a majority in a colour perception task. Sociometry, 32, 365–379.Moscovici, S. (1976). Social influence and social change. London: Academic Press.

Figure 1: a bar chart demonstrating the percentage of green responses by naïve participants in each condition.Results reported that the presence of a minority that consistently provided unusual responses influenced the judgments made by naive participants in that 32% of the consistent-minority condition conformed to the confederate response at least once and as can be deduced from figure 1 18% of all responses in this condition were green . However, the inconsistent minority had virtually no influence over the majority whatsoever, which supports Moscovici et al.’s (1969) claim that consistency is one the keys to minority influence. In summary either we need to confiscate Russell Brand’s thesaurus or wait until he inevitably begins to make contradictory statements before we switch off when he says something he didn’t intend to be a joke- power to the people. Rory MacLeodReferences Martin, R., & Hewstone, M. (2012). Minority influence: Revisiting Moscovici’s blue-green afterimage studies. In J. R. Smith, & S. Alexander-Haslam (Eds.), Social psychology: Revisiting the classic studies (pp. 91-106). London, England: Sage Publications. Moscovici, S., Lage, E., & Naffrechoux, M. (1969). Influence of a consistent minority on the responses of a majority in a colour perception task. Sociometry, 32, 365–379.Moscovici, S. (1976). Social influence and social change. London: Academic Press.

“Smell Like a Man, Man”

The more unique, bold and attention-grabbing an advertisement seems, the more standardized and clichéd it probably actually is. Or at least that that is what Goldenburg, Mazursky and Solomon (1999) believed. They identified 6 basic templates that 89% of 200 award-winning advertisements seemed to fall into. These templates included: Pictoral Analogy, Extreme Situation, Consequences, Competition, Interactive Experiment, Dimensionality Alteration. The above Old Spice ad created a lot of stir amongst viewers, and gained great popularity, reaching over 50 million views on YouTube. One explanation for its effectiveness may be due to its use of the consequences template, specifically the extreme consequences version. In the extreme consequences version, a set of situations is linked to a set of consequences via a linking operator. A consequence is a phenomenon, flow of events in the situation. “The situation in our example is a action, or behavior which results from the product attribute appearing in the message” (Goldenburg, Mazursky & Solomon, 1999, pp. 342). The consequences themselves need not be extreme, for example the advertisement repeatedly mentions that Old Spice will make “your man” smell more like a man (and less like a lady), an attainable consequence. In fact, this consequence needs to be both realistic and familiar to the audience. It is the linking operator which takes a select potential consequence and takes it to the extreme. This is demonstrated in Table 1 below. In this situation, smelling more like a man is a feasible goal. The advertisement takes this a step further by implying that once this goal is attained anything is possible – “your man” may become attractive like the Old Spice man who has tickets “for that thing you like”, diamonds and rides a horse. This linking operator is clearly quite extreme and absurd, and probably the very reason this ad has been so effective.Reference:Goldenberg, J., Mazursky, D., & Solomon, S. (1999). Creative sparks. Science, 285, 1495-1496.Shareen Rikhraj

In this situation, smelling more like a man is a feasible goal. The advertisement takes this a step further by implying that once this goal is attained anything is possible – “your man” may become attractive like the Old Spice man who has tickets “for that thing you like”, diamonds and rides a horse. This linking operator is clearly quite extreme and absurd, and probably the very reason this ad has been so effective.Reference:Goldenberg, J., Mazursky, D., & Solomon, S. (1999). Creative sparks. Science, 285, 1495-1496.Shareen Rikhraj

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- …

- 25

- Next Page »