It’s safe to say I was relieved to discover I am not the only one who experiences a large weight on my shoulders once someone has done something nice for me. Whether this be buying me a gift, an invitation or doing me a favour, I am greeted with a heavy sense of obligation to return said ‘thing’ to the individual who gave it to me. Cialdini’s (2007) chapter on reciprocation allowed me to recognise there is a universal response through the rule for reciprocation. This simply states that we should try to repay, in kind, what another person has provided us.The more you think about this, the more you realise its strength; the boxes of chocolates and lifts into town you have been giving your peers somehow make more sense. As a Psychology student, why I have committed so much time to being another’s participant, despite the ever-growing list of deadlines, has now become clear. It is a repayment of the time they have given me by being my participant. To give a more recent example, a friend of mine recently returned from Disneyland, somewhere, as a beloved Disney fan, I would love to go. She returned from her trip with a gift for me; a beautiful autograph book, filled with the signatures of my favourite characters. It is safe to say this is one of the most thoughtful gifts I have ever received and it is hugely appreciated. A week later, when my friend returned home from work, awaiting her was a cactus I had purchased from a plant stall. It wears a sombrero, has googly eyes, and sits proudly on her chest of drawers. At the time, the simple thought that she would love this cactus and therefore, I should buy it for her (looking back, I’m not sure a cactus would have ever made her shopping list, but it’s the thought that counts). It is now clear to me that the rule of reciprocation must have been at play; she had bought me a present thus, I owed her one in return. I have to say it was a form of comfort that my inability to say no to doing a favour for people and my ever growing habit of purchasing comical presents has a reason; and the answer to gaining back some of my free time and money isn’t simply becoming a nastier person.Cialdni suggests the power to say no comes from mentally restructuring the nice thing that has been done for us to its bare basics. If somebody in a store gives you a free sample, recognise it as a marketing technique and you will no longer feel the sense of obligation to purchase the product. After reading this, I felt empowered. I would no longer be submitting my free time and hard earnt money to the rue of reciprocation; I was free. As it turns out, I was naïve and premature in my conclusions. A friend asked me for a lift for him and his cousin to his brother’s wedding, and in return would pay me £10. In its simplicity; this is a business transaction; he was essentially paying me for my time and petrol, so in light of new found freedom I decided this was safe, and agreed. Yesterday we piled into my car and I drove them to the wedding. All had gone well until he handed me the money, £10 more than we had agreed. Well I found this very nice and drove home with a smile on my face. Within half an hour of dropping them off I had sent him a text and offered to pick him up from the wedding when it finished. It wasn’t until I had pressed send and was deciding what I would be spending my £20 on, with a cup of tea, that I realised I had been trapped by the rule of reciprocation once more. What’s more, I had been trapped despite my desperate attempts to keep it in my conscious awareness and not to be one of its victims.The rule of reciprocation exists for a reason; as Cianldni identifies, if we were always to accept favours and offer nothing in return it would not be long before this individual stopped their offerings. Chances are we would also be disliked through not fitting in with the social norms, norms that suggest we should ‘give and take’. It is clear my desperate attempts to avoid the rule at all costs failed miserably, but some level of awareness of its power will definitely be beneficial in the future, with better practice at saying no! References Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Reciprocation in Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Collins.

So, you want to be like Kylie Jenner? The Psychology of Celebrity Endorsement.

It might not surprise you, but Kylie Jenner doesn’t ACTUALLY buy her lavish clothes from the high street store ‘Miss Pap’, and no, she’s not ‘in love’ with her new Daniel Wellington watch – she’s got her own 50K alternative, you do the maths. So why is she posting all these products on her social media pages? Throughout this blog, I shall delve into the concept of ‘celebrity endorsements’, how these celebs use their roles in the social world, image and popularity to create persuasion like no other.  As of 2015, there has been recorded to be around $2.3 billion active social users. Within this, these social networks have earned what is estimated to be around $8.3 billion from advertising alone. It might not then be too unexpected to hear that a huge 91% of retail brands actually use 2 or more social medial channels, spending up to 20% of their budgets on this social media advertisement, (“96 amazing social media statistics and facts for 2016,” 2016). In an analysis of consumer responses to identical brand publicity in seven popular blogs and seven popular online magazines, Colliander and Dahlen (2011), found that blogs generated higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions. In today’s new, social media frenzied world; we see celebrity product placement, whether it be on Instagram, Twitter or Snapchat most of our browsing days. One might ask, why do celebrities use these product placements? Product placement isn’t a new craze, it can be seen throughout even the 1790’s – starting with royal endorsements and the promotion of ‘Wedgwood’, a pottery and chinaware company, (I know, nothing like the constant bombardment of the oh so ‘popular’ Boo Tea shakes; which apparently every celeb is using these days as a result of needing to ‘get back at it after the weekend’ – their diet presumably, see Figure 1).

As of 2015, there has been recorded to be around $2.3 billion active social users. Within this, these social networks have earned what is estimated to be around $8.3 billion from advertising alone. It might not then be too unexpected to hear that a huge 91% of retail brands actually use 2 or more social medial channels, spending up to 20% of their budgets on this social media advertisement, (“96 amazing social media statistics and facts for 2016,” 2016). In an analysis of consumer responses to identical brand publicity in seven popular blogs and seven popular online magazines, Colliander and Dahlen (2011), found that blogs generated higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions. In today’s new, social media frenzied world; we see celebrity product placement, whether it be on Instagram, Twitter or Snapchat most of our browsing days. One might ask, why do celebrities use these product placements? Product placement isn’t a new craze, it can be seen throughout even the 1790’s – starting with royal endorsements and the promotion of ‘Wedgwood’, a pottery and chinaware company, (I know, nothing like the constant bombardment of the oh so ‘popular’ Boo Tea shakes; which apparently every celeb is using these days as a result of needing to ‘get back at it after the weekend’ – their diet presumably, see Figure 1).Figure 1. (Celebrity Endorsement – Throughout the Ages, 2004)I mean, chances of them actually using these products are very slim – they’re only in it for he paycheck, as so beautifully demonstrated by Scott Disick in this hilarious post, see Figure 2:

Figure 2. (O’Toole, 2016)In this quickly deleted, but forever unforgotten; Instagram post, Scott Disick reveals details on his social media product placement extents by LITERALLY COPYING AND PASTING instructions given to him by Boo Tea on how to promote their product, a big mistake to make when you are earning up to $20,000 for posting. So why do these celebrities endorse products in which they probably have no need, or want; to use in the first place? In the 2000’s, research has shown that by having celebrity ambassadors promote your products, sales dramatically improve. An example demonstrating this finding comes from Nike – by using Tiger Woods to promote their golf balls, a $50 million increase in golf ball sales occurred between 1996 and 2002, (Celebrity Endorsement – Throughout the Ages, 2004). How did this simple use of a celebrity provide such dramatic increase in sales? We can look at this through the psychological phenomena..Social Proof

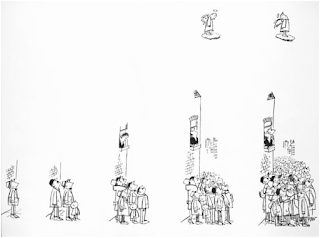

The more it appears everyone is doing it, the more likely others will join and agree. We seem to determine what is correct by looking at what other people think is correct, (Lun et al,. 2007). In reference to product placement, the way in which celebrity endorsements promote sales could be explained by this phenomena. A simple study by Latane and Darley (1968), demonstrates this perfectly. You’re sat in a room and suddenly it begins to fill with smoke, you’re going to get out, right? I mean, that seems like the obvious answer to me, however; this study exhibited different findings. The researchers found that where there were 2 passive confederates whom acted as though nothing was wrong, whilst the room filled with smoke; only 10% of the subjects in their study actually left the room or reported the problem. The rest of them carried on with their task, simply waving the smoke from their faces. Back to product placement – when we are constantly seeing that people, who are deemed to be representative of what is desirable in society; are using these certain products – we are going to want to use them to. It is this provision of both normative and informational influence which promotes us to try out these ‘great’ products. Like the participants in the above study, we simply follow what it looks like most people are doing. We don’t have to think ourselves that a certain product is good, we only need to think that others think it is good. Associative Learning

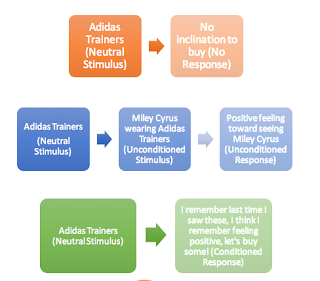

The more it appears everyone is doing it, the more likely others will join and agree. We seem to determine what is correct by looking at what other people think is correct, (Lun et al,. 2007). In reference to product placement, the way in which celebrity endorsements promote sales could be explained by this phenomena. A simple study by Latane and Darley (1968), demonstrates this perfectly. You’re sat in a room and suddenly it begins to fill with smoke, you’re going to get out, right? I mean, that seems like the obvious answer to me, however; this study exhibited different findings. The researchers found that where there were 2 passive confederates whom acted as though nothing was wrong, whilst the room filled with smoke; only 10% of the subjects in their study actually left the room or reported the problem. The rest of them carried on with their task, simply waving the smoke from their faces. Back to product placement – when we are constantly seeing that people, who are deemed to be representative of what is desirable in society; are using these certain products – we are going to want to use them to. It is this provision of both normative and informational influence which promotes us to try out these ‘great’ products. Like the participants in the above study, we simply follow what it looks like most people are doing. We don’t have to think ourselves that a certain product is good, we only need to think that others think it is good. Associative Learning  If you received an award in front of someone you previously were neutral towards, the probability of liking them increases. The positive aspects of the reward become associated with the person, (Lott & Lott, 1965).The effect of celebrity endorsements within the world of advertising can be explained through these associative learning principles. As demonstrated in Brian Till’s 1998 paper, when we see pictures of our favourite celebrities appearing on our newsfeed or in our search bars, we feel a certain amount of positive feeling – it is nice to see someone you like or perhaps look up to, right? By getting these celebrities with large fan bases to endorse products, we learn to associate these positive feelings we have about the celebrity alone with the product that they commonly endorse. Like the research findings from Lott and Lott (1965), the positive aspects of the celebrity become associated with the product. This leads us to think we have these positive feelings to, a certain trainer brand let’s say; and is going to make us much more likely to pick this brand over another when it comes to it. Look to the diagram above for a visual explanation!Source Credibility

If you received an award in front of someone you previously were neutral towards, the probability of liking them increases. The positive aspects of the reward become associated with the person, (Lott & Lott, 1965).The effect of celebrity endorsements within the world of advertising can be explained through these associative learning principles. As demonstrated in Brian Till’s 1998 paper, when we see pictures of our favourite celebrities appearing on our newsfeed or in our search bars, we feel a certain amount of positive feeling – it is nice to see someone you like or perhaps look up to, right? By getting these celebrities with large fan bases to endorse products, we learn to associate these positive feelings we have about the celebrity alone with the product that they commonly endorse. Like the research findings from Lott and Lott (1965), the positive aspects of the celebrity become associated with the product. This leads us to think we have these positive feelings to, a certain trainer brand let’s say; and is going to make us much more likely to pick this brand over another when it comes to it. Look to the diagram above for a visual explanation!Source Credibility Credibility is an important aspect to persuasion. If a message comes from a credible source, we are more likely to trust and act upon it. A study by Goldsmith, Lafferty, & Newell (2000), assessed the impact endorser credibility had on the shaping of attitudes towards brands. It was found that endorser credibility had the strongest impact on the participants’ attitudes towards the brand and purchase intentions, even more so than the corporates’ own credibility. If you are a huge fan of a certain celebrity, you probably perceive them as a trustworthy person. People who are trustworthy, physically attractive, have high social status and power must hold the correct attitudes. If they say that a product is good, it is good. People are more likely to attribute credibility to a company if they are using endorsement through a celebrity that you trust. Landscaping Techniques‘If you want to move a marble on a table, you can push it or you can lift the opposite end of the table. Pushing it is persuasion, lifting is pre-persuasion’ (Pratkanis, 2007) Celebrity endorsements can be considered as an example of pre-propaganda, through the creation of images and stereotypes – ‘It is cool to use this product because Justin Bieber does’; is a type of preconditioning of the public. Social Modelling

Credibility is an important aspect to persuasion. If a message comes from a credible source, we are more likely to trust and act upon it. A study by Goldsmith, Lafferty, & Newell (2000), assessed the impact endorser credibility had on the shaping of attitudes towards brands. It was found that endorser credibility had the strongest impact on the participants’ attitudes towards the brand and purchase intentions, even more so than the corporates’ own credibility. If you are a huge fan of a certain celebrity, you probably perceive them as a trustworthy person. People who are trustworthy, physically attractive, have high social status and power must hold the correct attitudes. If they say that a product is good, it is good. People are more likely to attribute credibility to a company if they are using endorsement through a celebrity that you trust. Landscaping Techniques‘If you want to move a marble on a table, you can push it or you can lift the opposite end of the table. Pushing it is persuasion, lifting is pre-persuasion’ (Pratkanis, 2007) Celebrity endorsements can be considered as an example of pre-propaganda, through the creation of images and stereotypes – ‘It is cool to use this product because Justin Bieber does’; is a type of preconditioning of the public. Social Modelling As most famously demonstrated in the ‘Bobo doll’ study, Bandura, Ross and Ross (1961), provided evidence for the case of learning via observation, imitation and modelling. People learn from one another. The celebrities you follow on your own social media feeds can be considered to be your important role models. It has been found that role models play a big part on teenager purchase intentions (Makgosa, 2010). By seeing your favourite role model endorse something, the likelihood of you to then consequently buy that product increases. We learn how to behave, in relation to our consumerism, by the way that our role models demonstrate we should. These celebrity endorsements are actually shaping our own purchase intentions. Agenda Setting and the Availability Heuristic

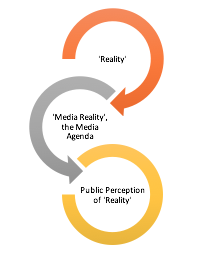

As most famously demonstrated in the ‘Bobo doll’ study, Bandura, Ross and Ross (1961), provided evidence for the case of learning via observation, imitation and modelling. People learn from one another. The celebrities you follow on your own social media feeds can be considered to be your important role models. It has been found that role models play a big part on teenager purchase intentions (Makgosa, 2010). By seeing your favourite role model endorse something, the likelihood of you to then consequently buy that product increases. We learn how to behave, in relation to our consumerism, by the way that our role models demonstrate we should. These celebrity endorsements are actually shaping our own purchase intentions. Agenda Setting and the Availability Heuristic This theory relates to the ability of the media to influence what topics are salient in the public agenda. Things which are placed highly on this agenda will appear to be more important and subsequently used to define the criteria used in the general public’s’ subsequent decisions. By setting agendas, the media (the products in which are regularly endorsed by celebrities, in this case) can limit the items that are thought about by the public exclusively to those that they want you thinking about. For example, repeated discussion of an issue in the media leads viewers to think it is more important, (Iyengar & Simon, 1983).Taking an instagram feed for example, if one were to follow a set of celebrities from the same sort of group, it would be likely to find that they were endorsing similar products. This provides these specific products to be top of my agenda. When it comes to purchases, I am much more likely to sway towards these. My ‘reality’ may be that I do not have any need for a Boo Tea prescription. However, when I see Louis Tomlinson, (along with many other celebs on my feed) tell me day to day that Boo Tea is an important aspect of his life, that becomes the ‘Media Reality’ – Boo Tea is needed. My new reality is a fabrication of what I have seen being promoted most regularly in the media, which leads me to want to purchase said product. This ties in with availability heuristics, a form of System 1 automatic and effortless thinking leading to preferential consumer patterns for those products most available to mind. Regularly endorsed products have seen, on average, a 2% increase in stock returns as compared to those less regularly endorsed by celebrities, (Elberse & Verleun 2012). Oh, so that’s why companies pay thousands to celebrities to post pictures of them with their products… Message Repetition and Mere ExposureWith a slightly similar basis to agenda setting and availability heuristics, message repetition can increase believability and acceptance. Mere, repeated exposure of an individual to a stimulus enhances his or her attitude towards it, the mere exposure provides a condition which makes the stimulus more accessible to perception, (Zajonk, 1968). The idea of mere exposure has been used to explain product placement (Vollmers & Mizerski, 1994). Mere exposure, in relation to product placement, can be explained like this – viewers will develop more favourable feelings towards a brand simply because of their repeated exposure to it – as demonstrated by Baker, (1999). This mere exposure doesn’t even need to be recalled, a simple repetition of exposure will lead to more favourable attitudes towards that brand (Janiszewski, 1993). It is common to see that celebrities have a select range of products in which they are regular endorsers for. This provides repetition of the message ‘buy this’ for each of those products to create stronger want to purchase said product. This explains the rise in sales for these regularly endorsed products. Theory of Planned Behaviour The theory of planned behaviour (Figure 3) comprises of three suggested components that lead to an intention to perform said behaviour.

This theory relates to the ability of the media to influence what topics are salient in the public agenda. Things which are placed highly on this agenda will appear to be more important and subsequently used to define the criteria used in the general public’s’ subsequent decisions. By setting agendas, the media (the products in which are regularly endorsed by celebrities, in this case) can limit the items that are thought about by the public exclusively to those that they want you thinking about. For example, repeated discussion of an issue in the media leads viewers to think it is more important, (Iyengar & Simon, 1983).Taking an instagram feed for example, if one were to follow a set of celebrities from the same sort of group, it would be likely to find that they were endorsing similar products. This provides these specific products to be top of my agenda. When it comes to purchases, I am much more likely to sway towards these. My ‘reality’ may be that I do not have any need for a Boo Tea prescription. However, when I see Louis Tomlinson, (along with many other celebs on my feed) tell me day to day that Boo Tea is an important aspect of his life, that becomes the ‘Media Reality’ – Boo Tea is needed. My new reality is a fabrication of what I have seen being promoted most regularly in the media, which leads me to want to purchase said product. This ties in with availability heuristics, a form of System 1 automatic and effortless thinking leading to preferential consumer patterns for those products most available to mind. Regularly endorsed products have seen, on average, a 2% increase in stock returns as compared to those less regularly endorsed by celebrities, (Elberse & Verleun 2012). Oh, so that’s why companies pay thousands to celebrities to post pictures of them with their products… Message Repetition and Mere ExposureWith a slightly similar basis to agenda setting and availability heuristics, message repetition can increase believability and acceptance. Mere, repeated exposure of an individual to a stimulus enhances his or her attitude towards it, the mere exposure provides a condition which makes the stimulus more accessible to perception, (Zajonk, 1968). The idea of mere exposure has been used to explain product placement (Vollmers & Mizerski, 1994). Mere exposure, in relation to product placement, can be explained like this – viewers will develop more favourable feelings towards a brand simply because of their repeated exposure to it – as demonstrated by Baker, (1999). This mere exposure doesn’t even need to be recalled, a simple repetition of exposure will lead to more favourable attitudes towards that brand (Janiszewski, 1993). It is common to see that celebrities have a select range of products in which they are regular endorsers for. This provides repetition of the message ‘buy this’ for each of those products to create stronger want to purchase said product. This explains the rise in sales for these regularly endorsed products. Theory of Planned Behaviour The theory of planned behaviour (Figure 3) comprises of three suggested components that lead to an intention to perform said behaviour. Figure 3. The first component, perceived behavioural control; is the belief that you can in fact control your own behaviour – this could be related to the idea of an internal locus of control. Perhaps you never thought you could be similar to your favourite celebrity, but where you see constant posts surrounding the sorts of products celebrities buy – you can do the same and increase your similarities! Next, we have social norms. The fact that so many credible sources are advertising how good a product is, and that they actually use it themselves; increases the norms relating to that product. Something which may not have been considered as a purchase is suddenly becoming something that most people are using, so you should too. Attitudes towards the behaviour relate to what you actually think about something, in terms of products this could be, for example, your opinions on the use of home teeth whitening kits, which are highly endorsed by celebrities. We may have certain predispositions towards the health implications these teeth whitening kits may have, but perhaps due to this high exposure of people in the public eye using them and having no problems, these attitudes could become more positive. Theory of planned behaviour suggests that where you have a combination of these 3 components, there will be intent to perform the behaviour – in this case being buying the product that has been endorsed by the celebrity.So as we can see, perhaps it isn’t so crazy to be paying a celebrity $20,000 to post a picture of your products after all. Although it does cost, it does work – and pretty effectively too. Celebrity endorsements are extremely powerful in nature, and whilst they are used to increase sales of non harmful products, one must worry about the implications if they were to endorse anything else.. References Baker, W. E. (1999). When can affective conditioning and mere exposure directly influence brand choice? Journal of Advertising, 28, 31-46.Bandura, A., Ross, D. & Ross, S.A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63, 575-82.Celebrity Endorsement – Through the Ages. (2004). Retrieved October 27, 2016, from http://ibscdc.org/Free%20Cases/Celebrity%20Endorsement%20Through%20the%20Ages%20p1.htm Colliander, J., & Dahlen, M. (2011). Following the fashionable friend: The power of social media – weighing the publicity effectiveness of Blogs versus online magazines. Journal of Advertising Research, 51, 313.Iberse, A., & Verleun, J. (2012). The economic value of celebrity endorsements. Journal of Advertising Research, 52, 149.Goldsmith, R. E., Lafferty, B. A., & Newell, S. J. (2000). The impact of corporate credibility and celebrity credibility on consumer reaction to advertisements and brands. Journal of Advertising, 29, 43–54.Iyengar, S., & Simon, A. (1993). News coverage of the gulf crisis and public opinion: A study of agenda-setting, priming, and framing. Communication Research, 20, 365–383.Janiszewski, C. (1993). Preattentive mere exposure effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 376-392. Latane, B., & Darley, J. M. (1968). Group Inhibition of Bystander Intervention in Emergencies. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 10, 215–221.Lott, A. J., & Lott, B. E. (1965). Group cohesiveness as interpersonal attraction: A review of relationships with antecedent and consequent variables. Psychological Bulletin, 64, 259–309Lun, J., Sinclair, S., Whitchurch, E. R., & Glenn, C. (2007). (Why) do I think what you think? Epistemic social tuning and implicit prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 957–972.Makgosa, R. (2010). The influence of vicarious role models on purchase intentions of Botswana teenagers. Young Consumers, 11, 307–319.O’Toole, C. (2016, May 19). Scott Disick appears to copy and paste Instagram product placement. Daily Mail. Retrieved October 27, 2016, from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3599720/Scott-Disick-appears-copy-paste-Instagram-product-placement-instructions-social-media.html#ixzz4OH9J2tkHPratkanis, A. R. (2007). The science of social influence: Advances and future progress. New York: Psychology Press.Till, B. D. (1998). Using celebrity endorsers effectively: Lessons from associative learning. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 7, 400–409.Vollmers, S., & Mizerski, R. (1994) A review and investigation into the effectiveness of product placement in films. In K. W. King (Ed.), Proceedings of the 1994 conference of the American Academy of Advertising (pp. 97-102). Athens, GA: American Academy of Advertising. Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9, 1-27.96 amazing social media statistics and facts for 2016. (2016, March 7). Retrieved October 27, 2016, from Marketing, https://www.brandwatch.com/2016/03/96-amazing-social-media-statistics-and-facts-for-2016/

Remember the ALS Ice Bucket Storm?

I will never forget the summer of 2014. I graduated high school, was eagerly anticipating my next big adventure at university, and had my brother pour a most debilitatingly ice-cold bucket of water over my head in the name of Lou Gehrig’s disease. A social media frenzy had taken over – the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge. The exact origins of the fad are unknown but the received wisdom is that it started with a Boston College student who was diagnosed with the disease in 2012. The challenge entailed the simple act of pouring an ice cold bucket of water over one’s head, uploading a video of the act to social media, making a donation to ALS research, and then nominating three other friends to take on the very same challenge. As of August 2014, The ALS Association had received $31.5 million in donations compared to $1.9 million during the same time period (July 29 to August 20) the previous year (Deighton, 2014) and the Ice Bucket Challenge had over 2.4 million tagged videos on Facebook (Stampler, 2014). But how exactly was this social media fad so effective in influencing hordes of individuals to donate towards ALS research? A simple explanation could have been its timing. The challenge was fortuitously instigated at the start of the summer, getting underway in June 2014 and peaking in August 2014. Obviously, high summer is a more suitable time to perform the act of tipping an ice-cold bucket of water over the head than, say, December. However, timing alone could not possibly account for such a social media frenzy and the sheer magnitude of donations that came in. Perhaps psychology can shed some light?1. Perceptual Salience. Could the influence of the ice bucket challenge have had its roots in our perceptual processes? Attention research has shown that the kind of stimuli that capture our gaze is the appearance of new visual objects (Yantis, 1993; Yantis & Jonides, 1996) and objects that are interesting (Elazary & Itty, 2008). Indeed, the ice-bucket challenge presents viewers with both a novel and visually interesting stimulus:-a campaign of this kind had never been implemented before and the nature of the challenge was peculiar. Thus, the novelty and uniqueness of the challenge was likely implicated in it becoming almost hysterically popular with the consequence being the number of donations that came in. 2. Commitment and ConsistencyAccording to Cialdini, one of the most effective ‘weapons of influence’ is our “obsessive desire to be consistent and to appear consistent with what we have already done” (1984 p 37). Compelling evidence for this comes from psychologist Thomas Moriarty who staged thefts on Jones Beach in New York. This study revealed that participants who had previously committed to protecting a confederate’s belongings after being requested to do so were much more likely to intervene during the theft with behaviours including chasing and stopping the thief, restraining the thief physically or even demanding an explanation for the theft (Moriarty, 1975). However, this should not be surprising as psychologist have long understood the power of consistency in motivating human behaviour. For example, Leon Festinger’s (1962) “Effort justification” is one explanation as to why participants of the ice bucket challenge are likely to have donated. One of the most classic examples of effort justification is Aronson and Mills’s (1952) study on a group of young women who volunteered to join a discussion group on the topic of the psychology of sex. The women were placed in a mild-embarrassment condition which involved reading aloud sex-related words (e.g. prostitute or virgin), a severe-embarrassment condition which involved saying highly sexual words (e.g. f*ck or c*ck) and a control group who did not read sex related words at all. All subjects then listened to a recording of a dull discussion about sexual behaviour in animals. When asked to rate the group and its members, the severe-embarrassment group’s ratings were significantly higher whereas control and mild-embarrassment groups did not differ. Aronson and Mills concluded that this was because those whose initiation process was more difficult (embarrassment equalling effort), had to increase their subjective value of the discussion group to resolve their subsequent cognitive dissonance. Stripping into one’s bathing suit, preparing a bucket of ice-cold water, asking one friend to pour the bucket over your head while another films it being poured all over you only for you to then upload it onto social media and to consequently challenge three other friends to do exactly the same thing in the name of ALS research is an effortful and uncomfortable process to say the least. Thus, it makes sense to assume the participants of the Ice Bucket Challenge – who persisted in this effortful task for ALS – donated for the same reason Moriarty’s participants chased the thief and Aronson and Mill’s participants rated their groups so highly – “to be and to appear consistent with what they had already done”.3. Public ImageA further explanation for the success of the ice bucket challenge could have been the communal and innately public nature of it. Psychologists are well aware of how desire to maintain a good reputation is also a powerful ‘weapon of influence’. Results from experimental economic games have shown that manipulating reputational opportunities affects prosocial behaviour and that opportunities for reputation formation can play an important role in sustaining cooperation and prosocial behaviour (Hayley & Fessler, 2005). The nature of the challenge allowed those taking part to publicly display social responsibility through charitable behaviour, and cooperation through accepting the challenge from a friend. Thus, desire to maintain a good reputation is likely to have contributed to the viral spread of the challenge and the magnitude of donations that came in. 4. Use of Role ModelsPerhaps one of the most powerful ‘weapon of influence’ utilised by this campaign was its involvement of celebrities. The influence of celebrities in the 21st century extends far beyond the traditional domain of the entertainment sector. They are important figures in campaigns for social change and the global internet is one of the major drivers of this phenomenon (Choi & Berger, 2010). Celebrities such as Oprah, Selena Gomez and Taylor Swift undertook the challenge. Perhaps more powerfully the challenge was not liable solely for celebrities but famous athletes, leading businessmen and influential entrepreneurs who too took part in the challenge. Lebron James, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg to name a few. For many, these individuals are important role models and research has shown how influential role models can be in dictating our behaviour. Role models can strongly influence purchase intentions and behaviour (Martin & Bush, 2000). An individual’s role model has even been implicated in the prediction of women’s career choices (Quimby & Santis, 2006). Thus, role models are looked up to by others and their actions are emulated by those admirers. The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge is evidence of this. For all those individuals on social media, seeing the singer or athlete they admire most donate and dedicate themselves to ALS was likely a very strong motivation to play a part in spreading the message and fundraising for the cause. But what became of it? As it turns out the funds raised from the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge helped identify a new gene associated with the disease the following year. Although only present in 3% of ALS cases, the NEK1 gene was found present in both inherited and sporadic forms of the disease which researchers believe will provide them a new target for the development of possible treatments (Cirulli et al., 2015). However small this breakthrough may seem, the ALS Ice Bucket challenge highlights two very important things: first, that working together we can bring about real change and awareness of social issues and second, never to underestimate the power of influence in dictating human behaviour. Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 177.Choi, C. J., & Berger, R. (2010). Ethics of celebrities and their increasing influence in 21st century society. Journal of business ethics, 91, 313-318.Cialdini, R. B. (1987). Influence (Vol. 3). A. Michel.Cirulli, E. T., Lasseigne, B. N., Petrovski, S., Sapp, P. C., Dion, P. A., Leblond, C. S., … & Ren, Z. (2015). Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science, 347, 1436-1441.Deighton, J. (2014, August 20). Why the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge is a Social Media Blockbuster. Retrieved from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/why-the-als-ice-bucket-challenge-is-a-social-media-blockbuster.Elazary, L., & Itti, L. (2008). Interesting objects are visually salient. Journal of vision, 8, 3-3.Haley, K. J., & Fessler, D. M. (2005). Nobody’s watching?: Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evolution and Human behavior, 26, 245-256.Moriarty, T. (1975). Crime, commitment, and the responsive bystander: Two field experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 370.Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford university press.Yantis, S. (1993). Stimulus-driven attention capture. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2, 156–161.Yantis, S., & Jonides, J. (1996). Attentional capture by abrupt onsets: New perceptual objects or visual masking? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 22, 1505–1513.Quimby, J. L., & Santis, A. M. (2006). The influence of role models on women’s career choices. The Career Development Quarterly, 54, 297-306. Stampler, L. (2014, August 15) This Is How Many Ice Bucket Challenge Videos People Have Posted on Facebook. Receieved from http://time.com/3117501/als-ice-bucket-challenge-videos-on-facebook/.

As of August 2014, The ALS Association had received $31.5 million in donations compared to $1.9 million during the same time period (July 29 to August 20) the previous year (Deighton, 2014) and the Ice Bucket Challenge had over 2.4 million tagged videos on Facebook (Stampler, 2014). But how exactly was this social media fad so effective in influencing hordes of individuals to donate towards ALS research? A simple explanation could have been its timing. The challenge was fortuitously instigated at the start of the summer, getting underway in June 2014 and peaking in August 2014. Obviously, high summer is a more suitable time to perform the act of tipping an ice-cold bucket of water over the head than, say, December. However, timing alone could not possibly account for such a social media frenzy and the sheer magnitude of donations that came in. Perhaps psychology can shed some light?1. Perceptual Salience. Could the influence of the ice bucket challenge have had its roots in our perceptual processes? Attention research has shown that the kind of stimuli that capture our gaze is the appearance of new visual objects (Yantis, 1993; Yantis & Jonides, 1996) and objects that are interesting (Elazary & Itty, 2008). Indeed, the ice-bucket challenge presents viewers with both a novel and visually interesting stimulus:-a campaign of this kind had never been implemented before and the nature of the challenge was peculiar. Thus, the novelty and uniqueness of the challenge was likely implicated in it becoming almost hysterically popular with the consequence being the number of donations that came in. 2. Commitment and ConsistencyAccording to Cialdini, one of the most effective ‘weapons of influence’ is our “obsessive desire to be consistent and to appear consistent with what we have already done” (1984 p 37). Compelling evidence for this comes from psychologist Thomas Moriarty who staged thefts on Jones Beach in New York. This study revealed that participants who had previously committed to protecting a confederate’s belongings after being requested to do so were much more likely to intervene during the theft with behaviours including chasing and stopping the thief, restraining the thief physically or even demanding an explanation for the theft (Moriarty, 1975). However, this should not be surprising as psychologist have long understood the power of consistency in motivating human behaviour. For example, Leon Festinger’s (1962) “Effort justification” is one explanation as to why participants of the ice bucket challenge are likely to have donated. One of the most classic examples of effort justification is Aronson and Mills’s (1952) study on a group of young women who volunteered to join a discussion group on the topic of the psychology of sex. The women were placed in a mild-embarrassment condition which involved reading aloud sex-related words (e.g. prostitute or virgin), a severe-embarrassment condition which involved saying highly sexual words (e.g. f*ck or c*ck) and a control group who did not read sex related words at all. All subjects then listened to a recording of a dull discussion about sexual behaviour in animals. When asked to rate the group and its members, the severe-embarrassment group’s ratings were significantly higher whereas control and mild-embarrassment groups did not differ. Aronson and Mills concluded that this was because those whose initiation process was more difficult (embarrassment equalling effort), had to increase their subjective value of the discussion group to resolve their subsequent cognitive dissonance. Stripping into one’s bathing suit, preparing a bucket of ice-cold water, asking one friend to pour the bucket over your head while another films it being poured all over you only for you to then upload it onto social media and to consequently challenge three other friends to do exactly the same thing in the name of ALS research is an effortful and uncomfortable process to say the least. Thus, it makes sense to assume the participants of the Ice Bucket Challenge – who persisted in this effortful task for ALS – donated for the same reason Moriarty’s participants chased the thief and Aronson and Mill’s participants rated their groups so highly – “to be and to appear consistent with what they had already done”.3. Public ImageA further explanation for the success of the ice bucket challenge could have been the communal and innately public nature of it. Psychologists are well aware of how desire to maintain a good reputation is also a powerful ‘weapon of influence’. Results from experimental economic games have shown that manipulating reputational opportunities affects prosocial behaviour and that opportunities for reputation formation can play an important role in sustaining cooperation and prosocial behaviour (Hayley & Fessler, 2005). The nature of the challenge allowed those taking part to publicly display social responsibility through charitable behaviour, and cooperation through accepting the challenge from a friend. Thus, desire to maintain a good reputation is likely to have contributed to the viral spread of the challenge and the magnitude of donations that came in. 4. Use of Role ModelsPerhaps one of the most powerful ‘weapon of influence’ utilised by this campaign was its involvement of celebrities. The influence of celebrities in the 21st century extends far beyond the traditional domain of the entertainment sector. They are important figures in campaigns for social change and the global internet is one of the major drivers of this phenomenon (Choi & Berger, 2010). Celebrities such as Oprah, Selena Gomez and Taylor Swift undertook the challenge. Perhaps more powerfully the challenge was not liable solely for celebrities but famous athletes, leading businessmen and influential entrepreneurs who too took part in the challenge. Lebron James, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg to name a few. For many, these individuals are important role models and research has shown how influential role models can be in dictating our behaviour. Role models can strongly influence purchase intentions and behaviour (Martin & Bush, 2000). An individual’s role model has even been implicated in the prediction of women’s career choices (Quimby & Santis, 2006). Thus, role models are looked up to by others and their actions are emulated by those admirers. The ALS Ice Bucket Challenge is evidence of this. For all those individuals on social media, seeing the singer or athlete they admire most donate and dedicate themselves to ALS was likely a very strong motivation to play a part in spreading the message and fundraising for the cause. But what became of it? As it turns out the funds raised from the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge helped identify a new gene associated with the disease the following year. Although only present in 3% of ALS cases, the NEK1 gene was found present in both inherited and sporadic forms of the disease which researchers believe will provide them a new target for the development of possible treatments (Cirulli et al., 2015). However small this breakthrough may seem, the ALS Ice Bucket challenge highlights two very important things: first, that working together we can bring about real change and awareness of social issues and second, never to underestimate the power of influence in dictating human behaviour. Aronson, E., & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 59, 177.Choi, C. J., & Berger, R. (2010). Ethics of celebrities and their increasing influence in 21st century society. Journal of business ethics, 91, 313-318.Cialdini, R. B. (1987). Influence (Vol. 3). A. Michel.Cirulli, E. T., Lasseigne, B. N., Petrovski, S., Sapp, P. C., Dion, P. A., Leblond, C. S., … & Ren, Z. (2015). Exome sequencing in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis identifies risk genes and pathways. Science, 347, 1436-1441.Deighton, J. (2014, August 20). Why the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge is a Social Media Blockbuster. Retrieved from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/why-the-als-ice-bucket-challenge-is-a-social-media-blockbuster.Elazary, L., & Itti, L. (2008). Interesting objects are visually salient. Journal of vision, 8, 3-3.Haley, K. J., & Fessler, D. M. (2005). Nobody’s watching?: Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evolution and Human behavior, 26, 245-256.Moriarty, T. (1975). Crime, commitment, and the responsive bystander: Two field experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 370.Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance (Vol. 2). Stanford university press.Yantis, S. (1993). Stimulus-driven attention capture. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2, 156–161.Yantis, S., & Jonides, J. (1996). Attentional capture by abrupt onsets: New perceptual objects or visual masking? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 22, 1505–1513.Quimby, J. L., & Santis, A. M. (2006). The influence of role models on women’s career choices. The Career Development Quarterly, 54, 297-306. Stampler, L. (2014, August 15) This Is How Many Ice Bucket Challenge Videos People Have Posted on Facebook. Receieved from http://time.com/3117501/als-ice-bucket-challenge-videos-on-facebook/.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- …

- 25

- Next Page »