“That night, image replaced the printed word as the natural language of politics.” (Baker, 1992)Kennedy vs NixonUS politics is particularly prominent at the moment and going a full day where it isn’t highlighted in the media is unlikely. The debates between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have specifically attracted a lot of attention from the public, with the first debate breaking records with an audience of 84 million viewers and the subsequent two averaging at around 70 million viewers. But where did it all begin? On the 26th of November 1960, John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon competed in the first televised debate. This particular debate has now become famous for highlighting the role television plays in politics. Mainly because many accounts of the debate have suggested a viewer – listener disagreement, where those who watched the debate on TV thought Kennedy had won but those that listened to the debate on radio thought Nixon to be the victor. Although now it has been classed as a myth with little evidential support (Vancil & Pendell, 1987), it sparked interest in how the personal image of candidates on TV can influence voters overall evaluations.Druckman (2003) revisited this notion that individuals will have different evaluations of the debate and the candidates (Kennedy vs Nixon) depending on the medium the debate is portrayed on. The findings were consistent with accounts of the debate, that TV image does matter and could have played an important role in the first Kennedy – Nixon debate. TV viewers were significantly more likely to think Kennedy won the debate than audio (radio) listeners and viewed Kennedy as having significantly more integrity than Nixon. Interestingly, it was found that watching the debate on TV primed participants to rely more on image (i.e integrity) and this played a significantly more important role for viewers than for listeners. Listeners relied only on their perceptions of leadership effectiveness compared to TV viewers who relied on both leadership effectiveness and image in evaluating the candidates. Moreover, the influence of perceptions of image for TV viewers lead to a decreased influence of whether the candidates and respondents agreed with the same issues but this remained a significant factor for listeners. What is it about image that persuades people to think candidates would be better presidents? Todorov and colleagues (2005) found that inferences of competence from facial features with exposures of just 1 second could correctly predict voting behaviour of US election outcomes. Those that were perceived to be more competent from their facial features were more likely to have won their elections. Mattes and colleagues (2010) found results consistent with this but with other positive and negative traits as well. In their study images of the two candidates in the race were shown together for both 33 ms and one second and participants quick judgements correlated with which candidates won the elections. As you can see from the table below those perceived to have more of the positive traits were more likely to have been chosen by the participants and actually have won their elections. Those with negative traits were less likely to be chosen by participants and less likely to have won their elections. Both Todorov et al (2005) and Mattes et al (2010) saw this as support that the evaluations of candidates individuals make are quick and effortless processes.

So how does this research relate to the Kennedy – Nixon debate? What was it about Nixon that lead to him being perceived so poorly on TV compared to radio? According to Hughes (1995), Nixon was still recovering from a knee surgery which he had spent time in hospital for which added to his already pale complexion and lead him to shift his weight a lot during the debate making him look uncomfortable. Moreover, in the black and white TV his dark beard made him look unshaven which his team attempted to cover up with ‘lazy shave cream’ but only added to his disastrous image making him sweat more under the extra lights requested by his team. All of this lead to Nixon being perceived as sickly and uncomfortable and thus possibly less competent. In contrast, Kennedy had spent time touring California and was subsequently tanned making him look healthy and well rested. Additionally, Kennedy wore a dark suit, making him stand out against the light background, compared to Nixon’s light grey suit which meant he blended into the background. Also during the debate, Kennedy directed his focus towards the camera and was seen making notes in reaction shots which made him appear self-confident. Whereas, Nixon often directed his focus towards Kennedy and was caught checking the time during reaction shots which lead him to being perceived as ’shifty eyed’ and thus less trust worthy. The comparison between the candidates of these non-verbal cues (only seen by those who watched the debate on TV) was the most likely reason that Nixon was reported to have lost the debate on TV compared to those that just listened to what he said on radio. How can Theories of Persuasion explain this?Petty and Cacioppo (1986) have proposed a dual process model called the Elaboration Likelihood Model which illustrates how individuals process information when they are persuaded (or not). Persuasion can take place via two routes Central or Peripheral. The central route refers to higher cognition or processing of information (arguments) and this route is taken when there is desire for beneficial outcomes, motivation to know and control and often when the individual cares about the topic. The peripheral route refers to lower cognition or processing most likely due to limited cognitive resources or capacity to process and often not a strong argument is needed as other peripheral cues or heuristics are used to make a decision. From what has been described above (how individuals can be influenced by appearance of candidates) it appears that often people may rely on heuristics (cognitive short-cuts) to make judgements about candidates. This seems counter-intuitive, especially when thinking about candidate elections for presidency, you would think individuals would use the central route as elections of this nature would be important to them and there would be a desire for beneficial outcomes. However, a paper by Lau and Redlawsk (2001) suggests otherwise: stating that the ‘average’ individual tends to be less motivated when making political decisions and uses the peripheral route. Lau and Redlawsk (2001) identified 5 types of politic heuristics and found that these were employed the majority of the time by participants (see table below). One of which is specifically relevant, ‘candidate appearance heuristic’. This heuristic refers to when individuals makes judgements based on specific cues about the physical appearance of a candidate (Reilly). This is particularly worrying as findings from Lenz and Lawson (2011) suggests that there is a greater reliance of this heuristic in those with less political knowledge and that ‘appealing-looking’ politicians will benefit more from increased television exposure.

So it appears that a candidate’s TV image is important as people tend rely on inferences made about appearance when making voting decisions. If you want to run for the US presidency do not make the same mistakes as Nixon. But then again, America voted in Donald Trump so it can not be the only factor given the things we see on TV about him.(see part 2 for some of the different persuasive techniques Trump employs in his debates with Hillary Clinton).References: Baker, R. (1992, November 1st). The 1992 Follies. The New York Times. Druckman, J. N. (2003). The Power of television images: The first Kennedy‐Nixon debate revisited. Journal of Politics, 65(2), 559-571.Hughes, S. R. (1995). The effects of nonverbal behavior in the 1992 televised presidential debates (Doctoral dissertation, Texas Tech University).Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. American Journal of Political Science, 951-971.Lenz, G. S., & Lawson, C. (2011). Looking the part: Television leads less informed citizens to vote based on candidates’ appearance. American Journal of Political Science, 55(3), 574-589.Mattes, K., Spezio, M., Kim, H., Todorov, A., Adolphs, R., & Alvarez, R. M. (2010). Predicting election outcomes from positive and negative trait assessments of candidate images. Political Psychology, 31(1), 41-58.Reilly, B. D. The Ties That Bind: Candidate Appearance and Party Heuristics.Todorov, A., Mandisodza, A. N., Goren, A., & Hall, C. C. (2005). Inferences of competence from faces predict election outcomes. Science, 308(5728), 1623-1626.Vancil, D. L., & Pendell, S. D. (1987). The myth of viewer‐listener disagreement in the first Kennedy‐Nixon debate. Central States Speech Journal, 38(1), 16-27.

#NoMakeUpSelfie

Selfies themselves have exploded in popularity alongside the ever-expanding world of social media. Ellen DeGeneres’ Oscars selfie in 2014 became the most retweeted post in history at 2,070,132 retweets by the end of the Oscars ceremony (Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them, 2014). Tom Hanks congratulated a newly-wed couple by sharing a selfie on Instagram, whilst the UK’s Prime Minister posed for selfies on the red carpet on Monday evening (Theresa Manyia, 2016), all captured in figure one. Figures from 2014 state over 1,000,000 #selfies are taken each day, with 50% of men and 52% of woman having taken a selfie (The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures, 2014). Perhaps it is no surprise then that the selfie phenomena provided an opportunity for the charity Cancer Research UK to raise over £8,000,000 (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). Figure One. Left to right: Ellen’s Oscar selfie, Tom Hanks wedding congratulations selfie, Theresa May posing for red carpet selfies with the public The #nomakeupselfie was initiated by Laura Lipmann, for a different reason and with a different hashtag, but before long the internet had worked its magic and the no make-up selfie was generating tens of thousands of tweets a day. Cancer Research UK noticed the hashtag gaining momentum and attached a donation text number to the posts, raising £2,000,000 in the first 48 hours (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). It is safe to say the no make-up selfies are a perfect example of ‘going viral’. How was it then that a simple selfie influenced so many people to donate? How was a viral phenomenon influencing people’s behaviour a) getting them to upload a post they would not usually post, and b) getting them to donate money they would not have considered doing before-hand? Below are various influence techniques that appear to have been at play throughout the #nomakeupselfie phenomena. Availability Heuristic and Social NormsThe availability heuristic suggests the easier something comes to mind, the higher we estimate the frequency of an event (Schwarz et al, 1991). Agenda setting theory extends this and suggests the media can manipulate what we think about by the frequency of which it shares a story (Walgrave & Aelst, 2006). With tens of thousands of woman engaging, it is not surprising the posts filled our timelines and reached mainstream media (Deller & Tilton, 2015). The no-make up selfie was then at the forefront of our minds, and we very quickly believed that everyone was doing it.Sherif and Sherif (1953) first defined social norms as our standards formed through our group interactions, that we will follow as individuals. Through the surge of no make-up selfie posts, the media ensured we perceived the no-make selfies as the latest norm. In the interest of fitting in and wanting to part of the in-group of our online friendship networks, we soon are likely to have taken the selfie ourselves and are contributing to the mass selfie uploads and adding to the growing donations. Celebrity Endorsement

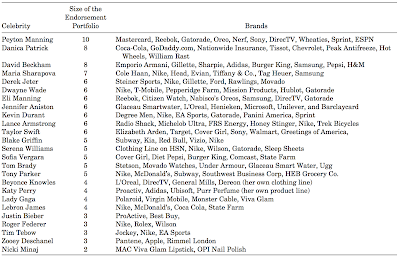

Figure One. Left to right: Ellen’s Oscar selfie, Tom Hanks wedding congratulations selfie, Theresa May posing for red carpet selfies with the public The #nomakeupselfie was initiated by Laura Lipmann, for a different reason and with a different hashtag, but before long the internet had worked its magic and the no make-up selfie was generating tens of thousands of tweets a day. Cancer Research UK noticed the hashtag gaining momentum and attached a donation text number to the posts, raising £2,000,000 in the first 48 hours (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014). It is safe to say the no make-up selfies are a perfect example of ‘going viral’. How was it then that a simple selfie influenced so many people to donate? How was a viral phenomenon influencing people’s behaviour a) getting them to upload a post they would not usually post, and b) getting them to donate money they would not have considered doing before-hand? Below are various influence techniques that appear to have been at play throughout the #nomakeupselfie phenomena. Availability Heuristic and Social NormsThe availability heuristic suggests the easier something comes to mind, the higher we estimate the frequency of an event (Schwarz et al, 1991). Agenda setting theory extends this and suggests the media can manipulate what we think about by the frequency of which it shares a story (Walgrave & Aelst, 2006). With tens of thousands of woman engaging, it is not surprising the posts filled our timelines and reached mainstream media (Deller & Tilton, 2015). The no-make up selfie was then at the forefront of our minds, and we very quickly believed that everyone was doing it.Sherif and Sherif (1953) first defined social norms as our standards formed through our group interactions, that we will follow as individuals. Through the surge of no make-up selfie posts, the media ensured we perceived the no-make selfies as the latest norm. In the interest of fitting in and wanting to part of the in-group of our online friendship networks, we soon are likely to have taken the selfie ourselves and are contributing to the mass selfie uploads and adding to the growing donations. Celebrity Endorsement Figure Two: Celebrity endorsement portfolios (Keating & Rice, 2013)Celebrity endorsement ties into the influence of both availability heuristic and social norms, with multiple brands using celebrities to advertise their goods, as outlined in figure two (Keating & Rice, 2013). Research by Keating and Rice (2013) measured recall of products when they were presented with a celebrity (celebrity cue) or with no cue. When looking at their results (displayed in figure three), it is understandable why such a vast majority of brands invest in celebrity marketing techniques, with moderate levels of celebrity cues significantly increasing recall of the products.

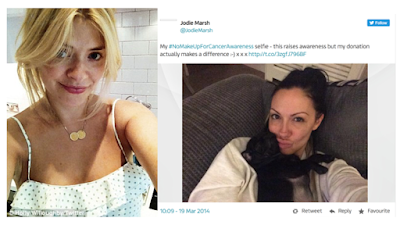

Figure Two: Celebrity endorsement portfolios (Keating & Rice, 2013)Celebrity endorsement ties into the influence of both availability heuristic and social norms, with multiple brands using celebrities to advertise their goods, as outlined in figure two (Keating & Rice, 2013). Research by Keating and Rice (2013) measured recall of products when they were presented with a celebrity (celebrity cue) or with no cue. When looking at their results (displayed in figure three), it is understandable why such a vast majority of brands invest in celebrity marketing techniques, with moderate levels of celebrity cues significantly increasing recall of the products.  Figure Three: Percentage of consumers who recalled the product with and without celebrity cues (Keating & Rice, 2013)If we extend this outside of purchasing environments, individuals are likely to have higher chances of recalling a given ‘thing’ if a celebrity has been associated with it. Once again, the availability heuristic is at play; if the celebrities are taking part (as demonstrated by Holly Willoughby and Jodie Marsh in figure three), everyone must be doing it. Thus, we are more likely to upload a no make-up selfie ourselves and make a donation in order to fit in with the ever-growing social norms.

Figure Three: Percentage of consumers who recalled the product with and without celebrity cues (Keating & Rice, 2013)If we extend this outside of purchasing environments, individuals are likely to have higher chances of recalling a given ‘thing’ if a celebrity has been associated with it. Once again, the availability heuristic is at play; if the celebrities are taking part (as demonstrated by Holly Willoughby and Jodie Marsh in figure three), everyone must be doing it. Thus, we are more likely to upload a no make-up selfie ourselves and make a donation in order to fit in with the ever-growing social norms. Figure Three. Left to right: Holly Willoughby’s and Jodie Marsh’s #nomakeupselfieRole ModelsIn addition, celebrities are traditionally seen as attractive and likeable individuals who are considered to be highly influential (Kamins et al, 1989), and therefore can be important influencers of behaviour (Bush, Martin & Bush, 2004). If individuals are aspiring to be like a celebrity role model, they could be more likely to model their behaviours (Singh, Vinnicombe & James, 2006) and in this case, also upload a no make-up selfie and make the donation to Cancer Research UK.Just AskOne of the key ‘weapons’ Cialdini (2000) identifies for influencing behaviour is simply asking for what you want. Research has shown, for example that 56% of females asked by a male stranger would agree to go on a date with him (Clark & Hatfield, 1989). As the #nomakeupselfie posts continued to grow, girls began to nominate three friends within their posts who should do the selfie next (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Like asking strangers on dates, people are more likely to conform to a behaviour when they are asked to do so directly, which could again, be increasing the likelihood of individuals posting no make-up selfies and donating. AttitudesThe British culture is one very heavily influenced by what others think of us. It is no secret we want to be viewed positively by our peers; a view that can be created through giving generously and selflessly (Li, Pickles & Savage, 2005). Compassion and generosity have been rated as two of the most important factors when rating how much we like other peers (Hartley et al, 2016). With these pre-conceived attitudes within the British culture, it is easy to see how so many were influenced to donate to Cancer Research UK; fast to be perceived as generous, selfless and therefore likeable to others. The no-make up selfies were considered both selfless through the donations and brave in uploading a photo in which they were not comfortable uploading, and as stated by Deller and Tilton (2015), selflessness and bravery is rewarded. ConsistencyCialdini (2000) also identifies consistency as one of the weapons in influencing behaviour. This is a phenomenon that states once we have made a stand, particularly in public, we are more likely to act consistent with this behaviour. For example, students were significantly more likely to stick to the estimates they had given for the length of a line when they declared the length publicly, as opposed to privately (Deutch & Gerard, 1955). Once individuals have taken their no-make up selfie and shared it on social media, they have made a public stand for their support for Cancer Research UK, and are therefore more likely to donate to the charity alongside their selfie, hence the £8,000,000 raised alongside the tens of thousands of selfies uploaded (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014).Above are just a select few of the techniques that may have encouraged people to participate in the #nomakeupselfie’s themselves, with others ranging from peer pressure to becoming a ‘killjoy’ for not taking part (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Whatever it was that made people get involved has got charities and marketers hunting it down in in order to become the next fund-raising phenomenon. If we are to take anything away from these viral selfies, realise and remember that behavioural influences can be used for the greater good. Thanks to the posts and donations of bare-faced woman, 10 new clinical trials could be funded, amongst other streams of research (#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered, 2014). A step closer to a cure for cancer has got to be making the world a better place. References#nomakeupselfie – why it worked. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2014/mar/25/nomakeupselfie-viral-campaign-cancer-research#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2014/03/25/nomakeupselfie-some-questions-answered/Bush, A. J., Martin, C. A., & Bush, V. D. (2004). Sports celebrity influence on the behavioral intentions of generation Y. Journal of Advertising Research, 44(01), 108-118.Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Collins.Clark, R. D. & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of psychology and human sexuality, 2, 39-55.Deller, R. A. & Tilton, S. (2015). Selfies as charitable meme: charity and national identity in the #nomakeupselfie and the #thumbsupforstephen campaigns. International journal of communication, 9, 1788-1805. Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The journal of abnormal and social psychology, 51(3), 629.Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them. (2014, March 7). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/mar/07/oscars-selfie-most-retweeted-everHartley, A. G., Furr, R. M., Helzer, E. G., Jayawickreme, E., Velasquez, K. R., & Fleeson, W. (2016). Morality’s centrality to liking, respecting, and understanding others. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1948550616655359.Kelting, K., & Rice, D. H. (2013). Should we hire David Beckham to endorse our brand? Contextual interference and consumer memory for brands in a celebrity’s endorsement portfolio. Psychology & Marketing, 30(7), 602-613.Li, Y., Pickles, A., & Savage, M. (2005). Social capital and social trust in Britain. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 109-123.Michael, A. K., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: the impact on advertising effectiveness and credibility. Journal of advertising, 18, 4-10.Radha, G. & Jija, P. (2013). Influence of celebrity endorsement on the consumer’s purchase decision. International journal of scientific and research publications, 3, 1-28.Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 61(2), 195.Sherif, M. & Sherif, C. W. (1953). Groups in harmony and tension. New York: Harper. Singh, V., Vinnicombe, S., & James, K. (2006). Constructing a professional identity: how young female managers use role models. Women in Management Review, 21(1), 67-81.The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures. (2014, March 19). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/selfie-statistics-2014/497309Theresa Maynia! (2016, October 31). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3891738/Theresa-Maynia-Selfies-autographs-red-carpet-PM-works-crowd-like-true-lister-Pride-Britain-awards.htmlWalgrave, S., & Van Aelst, P. (2006). The contingency of the mass media’s political agenda setting power: toward a preliminary theory. Journal of communication, 56, 88-109.

Figure Three. Left to right: Holly Willoughby’s and Jodie Marsh’s #nomakeupselfieRole ModelsIn addition, celebrities are traditionally seen as attractive and likeable individuals who are considered to be highly influential (Kamins et al, 1989), and therefore can be important influencers of behaviour (Bush, Martin & Bush, 2004). If individuals are aspiring to be like a celebrity role model, they could be more likely to model their behaviours (Singh, Vinnicombe & James, 2006) and in this case, also upload a no make-up selfie and make the donation to Cancer Research UK.Just AskOne of the key ‘weapons’ Cialdini (2000) identifies for influencing behaviour is simply asking for what you want. Research has shown, for example that 56% of females asked by a male stranger would agree to go on a date with him (Clark & Hatfield, 1989). As the #nomakeupselfie posts continued to grow, girls began to nominate three friends within their posts who should do the selfie next (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Like asking strangers on dates, people are more likely to conform to a behaviour when they are asked to do so directly, which could again, be increasing the likelihood of individuals posting no make-up selfies and donating. AttitudesThe British culture is one very heavily influenced by what others think of us. It is no secret we want to be viewed positively by our peers; a view that can be created through giving generously and selflessly (Li, Pickles & Savage, 2005). Compassion and generosity have been rated as two of the most important factors when rating how much we like other peers (Hartley et al, 2016). With these pre-conceived attitudes within the British culture, it is easy to see how so many were influenced to donate to Cancer Research UK; fast to be perceived as generous, selfless and therefore likeable to others. The no-make up selfies were considered both selfless through the donations and brave in uploading a photo in which they were not comfortable uploading, and as stated by Deller and Tilton (2015), selflessness and bravery is rewarded. ConsistencyCialdini (2000) also identifies consistency as one of the weapons in influencing behaviour. This is a phenomenon that states once we have made a stand, particularly in public, we are more likely to act consistent with this behaviour. For example, students were significantly more likely to stick to the estimates they had given for the length of a line when they declared the length publicly, as opposed to privately (Deutch & Gerard, 1955). Once individuals have taken their no-make up selfie and shared it on social media, they have made a public stand for their support for Cancer Research UK, and are therefore more likely to donate to the charity alongside their selfie, hence the £8,000,000 raised alongside the tens of thousands of selfies uploaded (#nomakeupselfie – why it worked, 2014).Above are just a select few of the techniques that may have encouraged people to participate in the #nomakeupselfie’s themselves, with others ranging from peer pressure to becoming a ‘killjoy’ for not taking part (Deller & Tilton, 2015). Whatever it was that made people get involved has got charities and marketers hunting it down in in order to become the next fund-raising phenomenon. If we are to take anything away from these viral selfies, realise and remember that behavioural influences can be used for the greater good. Thanks to the posts and donations of bare-faced woman, 10 new clinical trials could be funded, amongst other streams of research (#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered, 2014). A step closer to a cure for cancer has got to be making the world a better place. References#nomakeupselfie – why it worked. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2014/mar/25/nomakeupselfie-viral-campaign-cancer-research#nomakeupselfie- some questions answered. (2014, March 25). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://scienceblog.cancerresearchuk.org/2014/03/25/nomakeupselfie-some-questions-answered/Bush, A. J., Martin, C. A., & Bush, V. D. (2004). Sports celebrity influence on the behavioral intentions of generation Y. Journal of Advertising Research, 44(01), 108-118.Cialdini, R. B. (2007). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Collins.Clark, R. D. & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of psychology and human sexuality, 2, 39-55.Deller, R. A. & Tilton, S. (2015). Selfies as charitable meme: charity and national identity in the #nomakeupselfie and the #thumbsupforstephen campaigns. International journal of communication, 9, 1788-1805. Deutsch, M., & Gerard, H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The journal of abnormal and social psychology, 51(3), 629.Ellen’s Oscar selfie most retweeted ever – and more of us are taking them. (2014, March 7). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/mar/07/oscars-selfie-most-retweeted-everHartley, A. G., Furr, R. M., Helzer, E. G., Jayawickreme, E., Velasquez, K. R., & Fleeson, W. (2016). Morality’s centrality to liking, respecting, and understanding others. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1948550616655359.Kelting, K., & Rice, D. H. (2013). Should we hire David Beckham to endorse our brand? Contextual interference and consumer memory for brands in a celebrity’s endorsement portfolio. Psychology & Marketing, 30(7), 602-613.Li, Y., Pickles, A., & Savage, M. (2005). Social capital and social trust in Britain. European Sociological Review, 21(2), 109-123.Michael, A. K., Brand, M. J., Hoeke, S. A., Moe, J. C. (1989). Two-sided versus one-sided celebrity endorsements: the impact on advertising effectiveness and credibility. Journal of advertising, 18, 4-10.Radha, G. & Jija, P. (2013). Influence of celebrity endorsement on the consumer’s purchase decision. International journal of scientific and research publications, 3, 1-28.Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Strack, F., Klumpp, G., Rittenauer-Schatka, H., & Simons, A. (1991). Ease of retrieval as information: Another look at the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social psychology, 61(2), 195.Sherif, M. & Sherif, C. W. (1953). Groups in harmony and tension. New York: Harper. Singh, V., Vinnicombe, S., & James, K. (2006). Constructing a professional identity: how young female managers use role models. Women in Management Review, 21(1), 67-81.The year of the selfie- statistics, facts & figures. (2014, March 19). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/selfie-statistics-2014/497309Theresa Maynia! (2016, October 31). Retrieved November 1, 2016 from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3891738/Theresa-Maynia-Selfies-autographs-red-carpet-PM-works-crowd-like-true-lister-Pride-Britain-awards.htmlWalgrave, S., & Van Aelst, P. (2006). The contingency of the mass media’s political agenda setting power: toward a preliminary theory. Journal of communication, 56, 88-109.

Persuasion and Influence 2016-10-30 14:01:00

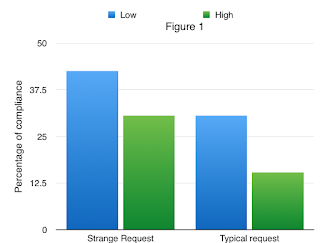

JUST ASK ‘I find you very attractive, will you go to bed with me?’ Elaine Hatfield carried out a revolutionary experiment in 1989, showing that 75% of men would go to bed with an averagely attractive woman if they just asked (Hatfield, 1989). Other research has confirmed the power of asking, by demonstrating that if you want something you should simply ask for it. Santos, Leve and Pratkanis (1994) suggested we have pre-set answers to questions. Therefore, an usual request is more likely to be completed as we will need to think about the answer. To demonstrate this, Santos, Leve and Pratkanis got confederates to ask a participant to borrow either a low or high amount of money, that was either strange e.g 17 cent or typical e.g a quarter. The results firstly showed that if you want to borrow money you should just ask as it is likely to get results. Secondly, people are more likely to give you money if you ask an usual request compared to a typical request as seen in Figure 1.

‘I find you very attractive, will you go to bed with me?’ Elaine Hatfield carried out a revolutionary experiment in 1989, showing that 75% of men would go to bed with an averagely attractive woman if they just asked (Hatfield, 1989). Other research has confirmed the power of asking, by demonstrating that if you want something you should simply ask for it. Santos, Leve and Pratkanis (1994) suggested we have pre-set answers to questions. Therefore, an usual request is more likely to be completed as we will need to think about the answer. To demonstrate this, Santos, Leve and Pratkanis got confederates to ask a participant to borrow either a low or high amount of money, that was either strange e.g 17 cent or typical e.g a quarter. The results firstly showed that if you want to borrow money you should just ask as it is likely to get results. Secondly, people are more likely to give you money if you ask an usual request compared to a typical request as seen in Figure 1. From the research done on the ‘just ask’ principle, I wanted to see how effective this technique would be in real life situations. I had bought a pair of jeans a couple of months ago, with the intention of giving them back to the shop. However, life got busy and I had missed the deadline for a refund. Seen as I had nothing to lose from the situation but money to gain, I decided to go into the shop and ask for a refund anyway. To my surprise, the shop assistant did not even bat an eyelid and completed the request without a seconds hesitation. Due to being astonished that I was about to get money for something I should not be, I even doubled checked that the shop assistant was aware of my lack of receipt. The request was still made. All I did was ask, and ended up getting money back in return.This is further proof of the ‘just ask’ principle. In the majority of situations, if you want something just ask! People drastically underestimate the power of asking, due to not believing it will be effective. However, as previous research such as Hatfield (1989) has shown, as well as my real life example illustrates, asking gets results!REFERNCES:Clark, R. D., & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2, 39-55.Santos, M. D., Leve, C., & Pratkanis, A. R. (1994). Hey buddy, can you spare seventeen cents? Mindful persuasion and the pique technique1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 755-764.

From the research done on the ‘just ask’ principle, I wanted to see how effective this technique would be in real life situations. I had bought a pair of jeans a couple of months ago, with the intention of giving them back to the shop. However, life got busy and I had missed the deadline for a refund. Seen as I had nothing to lose from the situation but money to gain, I decided to go into the shop and ask for a refund anyway. To my surprise, the shop assistant did not even bat an eyelid and completed the request without a seconds hesitation. Due to being astonished that I was about to get money for something I should not be, I even doubled checked that the shop assistant was aware of my lack of receipt. The request was still made. All I did was ask, and ended up getting money back in return.This is further proof of the ‘just ask’ principle. In the majority of situations, if you want something just ask! People drastically underestimate the power of asking, due to not believing it will be effective. However, as previous research such as Hatfield (1989) has shown, as well as my real life example illustrates, asking gets results!REFERNCES:Clark, R. D., & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender differences in receptivity to sexual offers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2, 39-55.Santos, M. D., Leve, C., & Pratkanis, A. R. (1994). Hey buddy, can you spare seventeen cents? Mindful persuasion and the pique technique1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 755-764.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- …

- 25

- Next Page »