A few years ago when my family and I were holidaying in NYC, we were stopped on the street by a man thrusting hats into our hands. Being naïve at the time to the power of the rule of reciprocity, my family and I duly accepted the hats. It was then of course that the man asked if we would kindly donate to a homeless charity. Feeling the pressure rise we felt compelled to donate at least a few dollars to the charity in question – An excellent use of the reciprocity rule on the part of the charity worker. Indeed, this rule has been proved effective in numerous scenarios, with Robert Cialdini (2009) documenting the case of the Krishna religious sect boosting their donations massively upon handing out flowers as ‘gifts’ in an airport. Empirically, support has been given from Regan (1971) who had two individuals taking part in an experiment on art appreciation. In reality, one ‘participant’ was actually a confederate who acted in two different ways: With some participants he bought a coke for himself and with others, he bought a coke for himself and the participant. Later, the confederate asked the participant if they would be willing to buy some raffle tickets. Regan found that participants who had been given the coke bought twice as many raffle tickets, even though the raffle tickets were more expensive than a can of coke!  Figure 1 – Regan (1971)Further evidence comes from Rind and Strohmetz (1999) who investigated reciprocity through the inclusion of a helpful message with a restaurant bill. Participants were either given a bill as usual or a bill with a message informing them that there was a special dinner featuring excellent seafood on a specified date. It was found that the mean tip percentage was higher in the message condition. This can be explained through the reciprocity rule because the waiter has informed the customer of something which is interpreted as helping behaviour. As such, the customer feels indebted to the waiter so increases their tip.In conclusion, the reciprocity rule is very effective in inducing compliance. Individuals are motivated to comply to a request because they feel indebted to the requester. ReferencesCialdini, R. B. (2009). Influence: Science and Practice. Boston: Pearson Education. Regan, D. T. (1971). Effects of a favour and liking on compliance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 627-639.Rind, B., & Strohmetz, D. (1999). Effect on restaurant tipping of a helpful message written on the back of customers’ checks. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29, 139-144.

Figure 1 – Regan (1971)Further evidence comes from Rind and Strohmetz (1999) who investigated reciprocity through the inclusion of a helpful message with a restaurant bill. Participants were either given a bill as usual or a bill with a message informing them that there was a special dinner featuring excellent seafood on a specified date. It was found that the mean tip percentage was higher in the message condition. This can be explained through the reciprocity rule because the waiter has informed the customer of something which is interpreted as helping behaviour. As such, the customer feels indebted to the waiter so increases their tip.In conclusion, the reciprocity rule is very effective in inducing compliance. Individuals are motivated to comply to a request because they feel indebted to the requester. ReferencesCialdini, R. B. (2009). Influence: Science and Practice. Boston: Pearson Education. Regan, D. T. (1971). Effects of a favour and liking on compliance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 627-639.Rind, B., & Strohmetz, D. (1999). Effect on restaurant tipping of a helpful message written on the back of customers’ checks. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29, 139-144.

Why did I nearly spend £100 on a piece of foam?

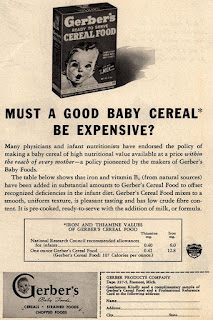

I like to think I do my research before I buy something, but I proved to myself on a rainy Sunday night when doing some online shopping that I do not. I was searching for yoga mats, and when faced with hundreds of different thicknesses, colours and materials I fell into the trap of sorting by price. Ever wondered who actually uses the ‘price high-low’ option? It was me, stupidly assuming that all of the cheap ones would be no good, so to save time I should go from the top. It was only when I was about to pay £100 for effectively a piece of pretty coloured foam that I realised I had read about this assumption. Cialdini had my back. It only takes a few cheap pieces of clothing to fall to pieces for us to learn the rule that expensive = good. This is ‘the common law of business balance’, that if you pay a small amount, you will not get a lot in return. Most of the time this rule is fine, it works, it saves us time, we get reinforced to use it again, and this yoga mat may well have been wonderful. The problem comes when the people selling us these items hijack this. Economics has a word for items which are in high demand simply because of the high prices asked, they are called ‘Veblen goods’ (Dolfsma, 2000). These ‘high quality items’ then become a status symbol (Leibenstein, 1950), as people know how much you have paid for that item, it is a means of displaying wealth a bit more subtly than literally throwing money around.  Advertisers are aware of this and have had to defend the low price of their productsThere’s another reason suggested for why we will willingly pay higher prices for a known brand over a identical item from an unknown one – consistency (Cialdini, 1987). We like to know what we’re getting, if we’ve bought something from that brand before and it was good, when buying another item we may but from there again. Another factor is commitment. If I have been walking round the gym with ‘Adidas’ written up my leggings (I have) when I go to buy a yoga mat I may look there first as I have made a visible commitment to their brand in the past. So I did end up saving myself money, but only because I spent my evening writing a blog post instead. Next time I’m tempted to do online shopping, I’ll do my research first. Dolfsma, W. (2000). Life and times of the Veblen Effect. History of Economic Ideas, 61-82.Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers’ demand. The quarterly journal of economics, 183-207.Cialdini, R. B. (1987). Influence (Vol. 3). A. Michel.

Advertisers are aware of this and have had to defend the low price of their productsThere’s another reason suggested for why we will willingly pay higher prices for a known brand over a identical item from an unknown one – consistency (Cialdini, 1987). We like to know what we’re getting, if we’ve bought something from that brand before and it was good, when buying another item we may but from there again. Another factor is commitment. If I have been walking round the gym with ‘Adidas’ written up my leggings (I have) when I go to buy a yoga mat I may look there first as I have made a visible commitment to their brand in the past. So I did end up saving myself money, but only because I spent my evening writing a blog post instead. Next time I’m tempted to do online shopping, I’ll do my research first. Dolfsma, W. (2000). Life and times of the Veblen Effect. History of Economic Ideas, 61-82.Leibenstein, H. (1950). Bandwagon, snob, and Veblen effects in the theory of consumers’ demand. The quarterly journal of economics, 183-207.Cialdini, R. B. (1987). Influence (Vol. 3). A. Michel.

On why the internet wants me to develop a shopping addiction

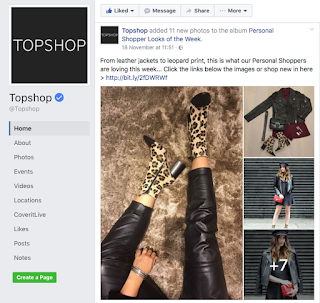

Public enemy number one.It only takes the once. One little google search, one quick browse. You think they haven’t got you this time. You think they’re forgotten you. But then, the next day, there it is. Topshop adverts abound. Not just on Facebook, but every site with paid-for advertising, there it is, bugging you. You only go looking in the first place because you heard there was a sale on and before you know it you’ve made a considerable order which you probably can’t afford (but it’s ok, you tell yourself- you’ve got student discount). You think that’s that. And perhaps it is. But for me, it never is. The next few weeks, most days I see a new post on my timeline from Topshop, even though I haven’t ‘liked’ their page. I start to become engrossed in their posts, actively seeking them out; their weekly ‘personal shopper looks of the week’, a particular favourite. Every week, I click back on to the website to check out their recommendations. But it’s not just Facebook. Soon, on Instagram, Topshop Personal Shopping is my new suggested follow. I oblige. And then it’s constant. I start to get upset if there isn’t a post. To remedy this, I follow each of the individual accounts of the personal shoppers. The staff in my local Topshop branch recognise me, as I now so regularly appear in store, returning the goods I have ordered in haste, but have changed my mind on once my sanity has returned.I have fallen for their advertising battery, hook, line and sinker. I take comfort only in that fact that it’s not just me and it’s definitely not just Topshop. This is a tale as old as, well, internet cookies. Whilst cookies are what got me hooked, Topshop, and many other brands alongside it, employ every tactic in their arsenal to get me to shop. I thought it might be best to take a look at just what is so effective about their advertising. The Availability Heuristic Proposed by Tversky and Kahneman (1973), this is the simple notion that we like, think about, and choose, what we can easily call to mind. This concept is something that almost every company on the internet has got down to a T.In this case, internet cookies tracking my activity then present me with personalised adverts all over the web, drumming the brand into my head until, when my friend invites me to her party and I know I need a new dress, the absolute first place I look is- you guessed it- Topshop. Subjective NormsFeaturing in the Theory of Planned Behaviour, and the Theory of Reasoned Action, subjective norms refer to what we perceive people around us think about the behaviour. Topshop present their potential shoppers with subjective norms in the form of their army of personal shoppers. These are women that are employed by Topshop as personal shoppers in store, but also regularly feature on Topshop’s social media accounts, wearing their top picks for the week. Not only this, but Topshop advertises their personal shoppers’ own Instagram accounts, a further treasure trove of Topshop endorsement. This exposure to these ‘normal’ girls covered head to toe in Topshop paraphernalia tells me that the people around me (i.e. on social media) think that Topshop is good and fashionable. I, therefore, think this ‘behaviour’ (i.e. shopping at Topshop) is good and fashionable. ScarcityIn one of my most recent episodes of my Topshop addiction, I saw a jacket being advertised by a personal shopper on Instagram. In typical form, I jumped straight on the website, and there it was; way too expensive for what it was, but I wanted it. I am perfectly aware that I spend too much money on clothes and I had been doing so well that I was about to shut the browser. And then. Then up popped a small bubble telling me that this item was selling fast. I knew I had to buy it then and there if I wanted it (I have been burnt too many times by my hesitation, leading to waiting months for a restock- by which time, I didn’t want it anymore). This is the persuasion tactic of scarcity. Scarcity, when an individual is lead to believe that there is a limited time frame or quantity available, serves as a form of social proof- where people assume behaviour shown by others in an attempt to behave correctly in a given situation. Though there is research evidence for both limited time and limited quantity, research suggests that a limited quantity tactic is more effective. For example, when Parker and Lehmann (2011) presented participants with a virtual store and asked them to select items from a set of options, he found that the participants showed a preference for items of limited availability. Reciprocity and the Loss LeaderCialdini, Green and Rusch (1992) suggest that there is good evidence that the rule of reciprocity governs a great deal of human behaviour. The rule suggests that we like those who like us, cooperate with those who cooperate with us, and we give with the expectation that we will be repaid. It is not immediately obvious how Topshop would employ this technique, until you understand the ‘Loss Leader’. The loss leader is a pricing strategy in which products or services are provided at a loss, in order to generate sales for other profitable products and services.When I visited one of Topshop stores, and they didn’t have the shoes I wanted in the size I needed, the assistant gave me a code for free next day delivery (usually costing £6) so I could order them online. I thought the assistant was being kind but really, this is just a loss leader. Topshop sacrifices the delivery charge in order to gain my business, purchasing quite expensive boots which I imagine have sky high profit margins. This is a tactic seen all over the web- it seems online outlets are constantly advertising free delivery. No matter what negotiations go on with the couriers, its unlikely Topshop and other brands make no loss on such ‘generosity’. It is all a very well thought out plan to drive up business. So, armed with all this knowledge, most people would think I am a reformed character, that I am immune to this battery of persuasion, and I’d like to tell you that I am, but one look at my wardrobe (and my bank account) will tell a different story. They say knowledge is power but, in this case, knowledge is doing the same as everyone else does, and just feeling like an idiot when you do it. References Cialdini, R. B., Green, B. L., & Rusch, A. J. (1992). When tactical pronouncements of change become real change: The case of reciprocal persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(1), 30–40.Parker, J. R., & Lehmann, D. R. (2011). When shelf-based scarcity impacts consumer preferences. Journal of Retailing, 87(2), 142–155.Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232.

Public enemy number one.It only takes the once. One little google search, one quick browse. You think they haven’t got you this time. You think they’re forgotten you. But then, the next day, there it is. Topshop adverts abound. Not just on Facebook, but every site with paid-for advertising, there it is, bugging you. You only go looking in the first place because you heard there was a sale on and before you know it you’ve made a considerable order which you probably can’t afford (but it’s ok, you tell yourself- you’ve got student discount). You think that’s that. And perhaps it is. But for me, it never is. The next few weeks, most days I see a new post on my timeline from Topshop, even though I haven’t ‘liked’ their page. I start to become engrossed in their posts, actively seeking them out; their weekly ‘personal shopper looks of the week’, a particular favourite. Every week, I click back on to the website to check out their recommendations. But it’s not just Facebook. Soon, on Instagram, Topshop Personal Shopping is my new suggested follow. I oblige. And then it’s constant. I start to get upset if there isn’t a post. To remedy this, I follow each of the individual accounts of the personal shoppers. The staff in my local Topshop branch recognise me, as I now so regularly appear in store, returning the goods I have ordered in haste, but have changed my mind on once my sanity has returned.I have fallen for their advertising battery, hook, line and sinker. I take comfort only in that fact that it’s not just me and it’s definitely not just Topshop. This is a tale as old as, well, internet cookies. Whilst cookies are what got me hooked, Topshop, and many other brands alongside it, employ every tactic in their arsenal to get me to shop. I thought it might be best to take a look at just what is so effective about their advertising. The Availability Heuristic Proposed by Tversky and Kahneman (1973), this is the simple notion that we like, think about, and choose, what we can easily call to mind. This concept is something that almost every company on the internet has got down to a T.In this case, internet cookies tracking my activity then present me with personalised adverts all over the web, drumming the brand into my head until, when my friend invites me to her party and I know I need a new dress, the absolute first place I look is- you guessed it- Topshop. Subjective NormsFeaturing in the Theory of Planned Behaviour, and the Theory of Reasoned Action, subjective norms refer to what we perceive people around us think about the behaviour. Topshop present their potential shoppers with subjective norms in the form of their army of personal shoppers. These are women that are employed by Topshop as personal shoppers in store, but also regularly feature on Topshop’s social media accounts, wearing their top picks for the week. Not only this, but Topshop advertises their personal shoppers’ own Instagram accounts, a further treasure trove of Topshop endorsement. This exposure to these ‘normal’ girls covered head to toe in Topshop paraphernalia tells me that the people around me (i.e. on social media) think that Topshop is good and fashionable. I, therefore, think this ‘behaviour’ (i.e. shopping at Topshop) is good and fashionable. ScarcityIn one of my most recent episodes of my Topshop addiction, I saw a jacket being advertised by a personal shopper on Instagram. In typical form, I jumped straight on the website, and there it was; way too expensive for what it was, but I wanted it. I am perfectly aware that I spend too much money on clothes and I had been doing so well that I was about to shut the browser. And then. Then up popped a small bubble telling me that this item was selling fast. I knew I had to buy it then and there if I wanted it (I have been burnt too many times by my hesitation, leading to waiting months for a restock- by which time, I didn’t want it anymore). This is the persuasion tactic of scarcity. Scarcity, when an individual is lead to believe that there is a limited time frame or quantity available, serves as a form of social proof- where people assume behaviour shown by others in an attempt to behave correctly in a given situation. Though there is research evidence for both limited time and limited quantity, research suggests that a limited quantity tactic is more effective. For example, when Parker and Lehmann (2011) presented participants with a virtual store and asked them to select items from a set of options, he found that the participants showed a preference for items of limited availability. Reciprocity and the Loss LeaderCialdini, Green and Rusch (1992) suggest that there is good evidence that the rule of reciprocity governs a great deal of human behaviour. The rule suggests that we like those who like us, cooperate with those who cooperate with us, and we give with the expectation that we will be repaid. It is not immediately obvious how Topshop would employ this technique, until you understand the ‘Loss Leader’. The loss leader is a pricing strategy in which products or services are provided at a loss, in order to generate sales for other profitable products and services.When I visited one of Topshop stores, and they didn’t have the shoes I wanted in the size I needed, the assistant gave me a code for free next day delivery (usually costing £6) so I could order them online. I thought the assistant was being kind but really, this is just a loss leader. Topshop sacrifices the delivery charge in order to gain my business, purchasing quite expensive boots which I imagine have sky high profit margins. This is a tactic seen all over the web- it seems online outlets are constantly advertising free delivery. No matter what negotiations go on with the couriers, its unlikely Topshop and other brands make no loss on such ‘generosity’. It is all a very well thought out plan to drive up business. So, armed with all this knowledge, most people would think I am a reformed character, that I am immune to this battery of persuasion, and I’d like to tell you that I am, but one look at my wardrobe (and my bank account) will tell a different story. They say knowledge is power but, in this case, knowledge is doing the same as everyone else does, and just feeling like an idiot when you do it. References Cialdini, R. B., Green, B. L., & Rusch, A. J. (1992). When tactical pronouncements of change become real change: The case of reciprocal persuasion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(1), 30–40.Parker, J. R., & Lehmann, D. R. (2011). When shelf-based scarcity impacts consumer preferences. Journal of Retailing, 87(2), 142–155.Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- …

- 25

- Next Page »