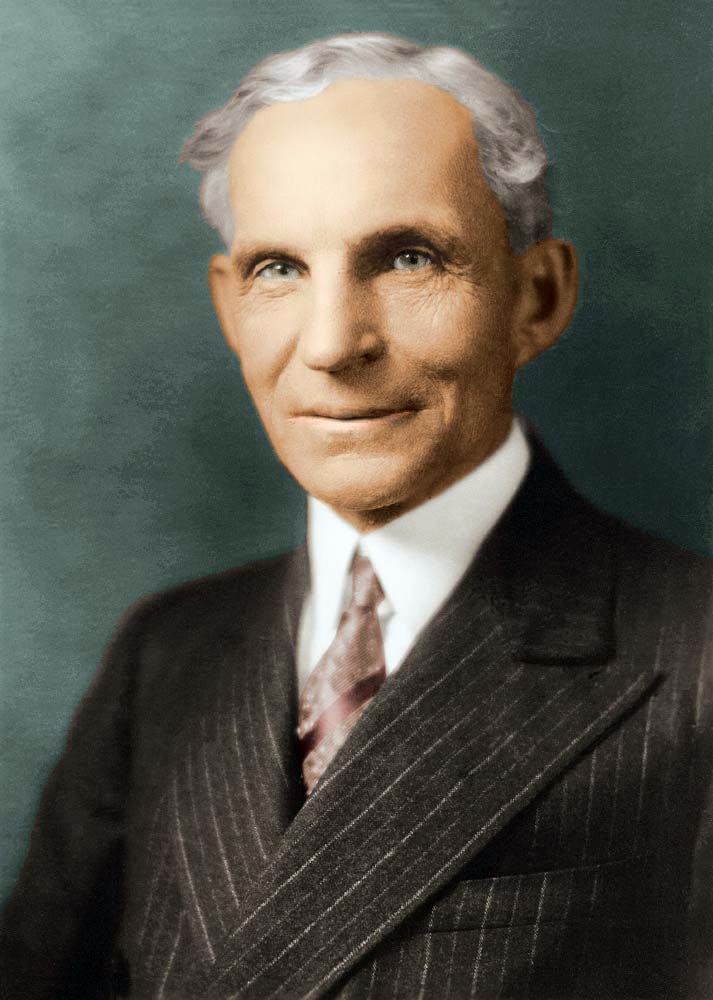

Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company, once said, “Thinking is some of the hardest work there is, which is probably why so few people engage in it.” Thinking may not be like manual labor but for those of you who engage in deep thought you know it’s tiring! But why is that the case? Here are a couple of reasons: “The brain represents only about 2% of most people’s body weight, yet it accounts for about 20% of the body’s total energy use.” – from Brain Rules by John Medina.“The brain consumes 300% more caloric intake when engaged in cognitive evaluation and logical thinking than when in the automatic mode.” – from The 7 Triggers to Yes by Russ GrangerBottom line – that small piece of grey matter in our skulls requires a lot of energy and when used to capacity it leaves us quite tired. We do what we can to avoid working harder than we have to so Henry Ford might have been correct about our aversion to the hard work of thinking. Or perhaps our ability to reduce our thinking and save energy is a survival mechanism.Whether it’s laziness or survival, one thing is for sure, when we can think less and conserve energy we usually do it. This is important to understand if you want to become a better persuader. In March 2009, ABC News featured an article titled Expert Advice Shuts Your Brain Down. Here’s my Cliff’s Notes version of the article:Two dozen Emory University students are given complicated financial problems to solve. They’re hooked to brain imaging equipment so their neural activity can be observed. As they try to figure out answers to the problems their brains are hard at work! Eventually a professor from Emory University is introduced to the class, and it’s made known he’s also an advisor to the U.S. Federal Reserve. In other words, he’s a very smart financial guy. As he begins to give the students advice, even advice he knows is bad, their brains “flat lined” because they stopped critically thinking. So what went on there? From the perspective of the psychology of persuasion, the principle of authority was engaged. This principle of influence tells us people defer to those with superior knowledge or wisdom when making decisions.I like to share the ABC account because it illustrates an important fact about persuasion – it’s not pop psychology or some fad. When a principle like authority is engaged correctly it causes physiological changes in the brain and that’s part of the reason the principles of influence can be so effective when it comes to persuading others.Consider the Emory University students. Left on their own, they had to work hard to come up with answers. However, when a credentialed individual who is viewed as much smarter than they are comes into the equation everything changes. They can cease from the hard work of thinking!Each of us does this at different times. This is why we pay accountants to do our taxes, lawyers to defend us in court or stockbrokers to invest for us. We don’t want to do the heavy lifting associated with each of those mental activities. How does this understanding help you be a more effective persuader? Two ways.First, the more someone understands your expertise the less critical they will be of your ideas and recommendations. That’s not to say everyone will do what you want nor am I advocating trying to get people “brain dead” in order to persuade them. However, when they understand your expertise they will more readily accept your position just as the Emory University students did with the professor. You can establish your credentials on your business card (title and designations earned), through letters of reference and introduction, speaker bios, years in business, how you dress, the car you drive, etc. Each of these can indicate success which usually carries with it the assumption of some expertise.The second way to engage this is using outside sources. You may be an expert or maybe you’ve not established expertise yet. Either way, when you bring outside sources – other experts, graphs, charts, stats, etc., into the persuasion equation, you begin to bring authority into the mix and people will more readily accept what you’re sharing. How will you apply this concept? Next time you go into a situation where you need to be persuasive make sure people know your credentials up front. Doing so after the fact does little good because the person you’re attempting to persuade might have already made up his or her mind. If you go this route, do so by engaging someone to introduce you either in person or by email. When you do this, make sure the person making the introduction knows the most important credentials you have.The other thing you want to do is look for valid stats, charts, quotes or other references that show you’ve done your homework and there’s respected support for what you propose.Here’s an example of putting this into practice. I’m in the insurance industry and work for an insurance company. Quite often insurance agents will call their underwriter for more in-depth understanding of coverages or insurance provisions. An underwriter might answer the agent’s question off the cuff because they know the answer. However, if it’s not what the agent wants to hear the agent might contend with the underwriter. It’s a good bet the underwriter’s knowledge came from continuing education so why not cite the source of knowledge? Here’s how I would advise an underwriter to answer:“That’s a great question. I remember when I was studying for my CPCU…”Now the answer is not just opinion because it’s backed by the authority of the CPCU Institute.Sometimes seemingly simple things like citing a source or establishing credentials up front can make all the difference in turning a no into a yes.

Henry Ford, founder of the Ford Motor Company, once said, “Thinking is some of the hardest work there is, which is probably why so few people engage in it.” Thinking may not be like manual labor but for those of you who engage in deep thought you know it’s tiring! But why is that the case? Here are a couple of reasons: “The brain represents only about 2% of most people’s body weight, yet it accounts for about 20% of the body’s total energy use.” – from Brain Rules by John Medina.“The brain consumes 300% more caloric intake when engaged in cognitive evaluation and logical thinking than when in the automatic mode.” – from The 7 Triggers to Yes by Russ GrangerBottom line – that small piece of grey matter in our skulls requires a lot of energy and when used to capacity it leaves us quite tired. We do what we can to avoid working harder than we have to so Henry Ford might have been correct about our aversion to the hard work of thinking. Or perhaps our ability to reduce our thinking and save energy is a survival mechanism.Whether it’s laziness or survival, one thing is for sure, when we can think less and conserve energy we usually do it. This is important to understand if you want to become a better persuader. In March 2009, ABC News featured an article titled Expert Advice Shuts Your Brain Down. Here’s my Cliff’s Notes version of the article:Two dozen Emory University students are given complicated financial problems to solve. They’re hooked to brain imaging equipment so their neural activity can be observed. As they try to figure out answers to the problems their brains are hard at work! Eventually a professor from Emory University is introduced to the class, and it’s made known he’s also an advisor to the U.S. Federal Reserve. In other words, he’s a very smart financial guy. As he begins to give the students advice, even advice he knows is bad, their brains “flat lined” because they stopped critically thinking. So what went on there? From the perspective of the psychology of persuasion, the principle of authority was engaged. This principle of influence tells us people defer to those with superior knowledge or wisdom when making decisions.I like to share the ABC account because it illustrates an important fact about persuasion – it’s not pop psychology or some fad. When a principle like authority is engaged correctly it causes physiological changes in the brain and that’s part of the reason the principles of influence can be so effective when it comes to persuading others.Consider the Emory University students. Left on their own, they had to work hard to come up with answers. However, when a credentialed individual who is viewed as much smarter than they are comes into the equation everything changes. They can cease from the hard work of thinking!Each of us does this at different times. This is why we pay accountants to do our taxes, lawyers to defend us in court or stockbrokers to invest for us. We don’t want to do the heavy lifting associated with each of those mental activities. How does this understanding help you be a more effective persuader? Two ways.First, the more someone understands your expertise the less critical they will be of your ideas and recommendations. That’s not to say everyone will do what you want nor am I advocating trying to get people “brain dead” in order to persuade them. However, when they understand your expertise they will more readily accept your position just as the Emory University students did with the professor. You can establish your credentials on your business card (title and designations earned), through letters of reference and introduction, speaker bios, years in business, how you dress, the car you drive, etc. Each of these can indicate success which usually carries with it the assumption of some expertise.The second way to engage this is using outside sources. You may be an expert or maybe you’ve not established expertise yet. Either way, when you bring outside sources – other experts, graphs, charts, stats, etc., into the persuasion equation, you begin to bring authority into the mix and people will more readily accept what you’re sharing. How will you apply this concept? Next time you go into a situation where you need to be persuasive make sure people know your credentials up front. Doing so after the fact does little good because the person you’re attempting to persuade might have already made up his or her mind. If you go this route, do so by engaging someone to introduce you either in person or by email. When you do this, make sure the person making the introduction knows the most important credentials you have.The other thing you want to do is look for valid stats, charts, quotes or other references that show you’ve done your homework and there’s respected support for what you propose.Here’s an example of putting this into practice. I’m in the insurance industry and work for an insurance company. Quite often insurance agents will call their underwriter for more in-depth understanding of coverages or insurance provisions. An underwriter might answer the agent’s question off the cuff because they know the answer. However, if it’s not what the agent wants to hear the agent might contend with the underwriter. It’s a good bet the underwriter’s knowledge came from continuing education so why not cite the source of knowledge? Here’s how I would advise an underwriter to answer:“That’s a great question. I remember when I was studying for my CPCU…”Now the answer is not just opinion because it’s backed by the authority of the CPCU Institute.Sometimes seemingly simple things like citing a source or establishing credentials up front can make all the difference in turning a no into a yes.Brian Ahearn, CMCT® Chief Influence Officer influencePEOPLE Helping You Learn to Hear “Yes”.Cialdini “Influence” Series! Would you like to learn more about influence from the experts? Check out the Cialdini “Influence” Series featuring Cialdini Method Certified Trainers from around the world.